Holiday Pops!

December 6, 2024 at 7:30 pm

December 7, 2024 at 2 pm

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Holiday Pops!

Friday, December 6, 2024 at 7:30 pm

Saturday, December 7, 2024 at 2 pm

Mary Stuart Rogers Theater, Gallo Center for the Arts

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this weekend’s performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

The Four Seasons Mixtape

November 1 & 2, 2024 at 7:30 pm

VISIT MOBILE PROGRAM →

READ OUR PROGRAM NOTES →

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE VERSION →

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

The Four Seasons Mixtape

November 1 & 2, 2024 at 7:30 pm

Gallo Center for the Arts, Mary Stuart Rogers Theater

Nicholas Hersh, conductor

Audrey Wright, violin

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Program Notes: The Four Seasons Mixtape

Notes about:

Mendelssohn’s Overture from A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Ortiz’s La Calaca for String Orchestra

The Four Seasons Mixtape:

Vivaldi’s L’estate (Summer)

Richter’s Autumn from The Four Seasons Recomposed

Ysaÿe’s Chant d’hiver (Wintersong)

Piazzolla’s Primavera portena (Beunos Aires Spring)

Program Notes for November 1 & 2, 2024

The Four Seasons Mixtape

Felix Mendelssohn

Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Op. 21

Composer: born February 3, 1809, Hamburg; died November 4, 1847, Leipzig

Work composed: 1826

World premiere: Mendelssohn’s first version of the Overture was a two-piano arrangement for himself and his sister Fanny, which they premiered at their home in Berlin on November 19, 1826, for their piano teacher, Ignaz Moscheles. After that performance, Mendelssohn scored the work for orchestra and conducted the first performance of the orchestral version himself the following February in the city of Stettin.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, tuba, timpani, and strings.

Estimated duration: 11 minutes

In July 1826, Felix Mendelssohn began composing what would become one of his most enduring works. Immediately upon its completion, the Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream established the 17-year-old Mendelssohn as a composer of depth and astonishing maturity.

Young Felix and his family were ardent fans of Shakespeare, whose works had been translated into German in 1790. Mendelssohn’s grandfather Moses had read the plays in English and had attempted some translations of his own, including bits from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Felix and his older sister, the equally talented Fanny, immediately took to the fanciful play and staged a series of at-home performances, each child playing multiple roles. In a letter to their sister Rebecka some years after the Overture was composed, Fanny wrote, “Yesterday we were thinking about how the Midsummer Night’s Dream has always been such an inseparable part of our household, how we read all the different roles at various ages, from Peaseblossom to Hermia and Helena … We have really grown up together with the Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Felix, in particular, has made it his own.”

Much more than a simple introduction, Mendelssohn’s Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream serves as the perfect musical description of Shakespeare’s play, which was Mendelssohn’s intention. He thought of the work as a kind of mini-tone poem, rather than a musical prologue to the play itself. In just twelve minutes, Mendelssohn captures the airy magic that imbues the story: the opening chords representing the enchanted forest; the lissome, iridescent violin passages evoking fairies fluttering here and there; the alternately affectionate and turbulent encounters among the four lovers; the dismaying bray of Bottom after he is transformed into a donkey. It is a stunning achievement for a composer of any age.

While he was at work on the Overture, Mendelssohn played violin in an orchestra that performed the overture to Carl Maria von Weber’s opera Oberon. In a letter to his father and sister, Mendelssohn sketched out several of its themes, all musical representations of ideas from the opera’s libretto. This experience suggested to Mendelssohn that he intertwine recurring motifs into his own Overture that would, in his words, “weave like delicate threads throughout the whole.”

Gabriela Ortiz

La Calaca for String Orchestra (The Skull)

Composer: born December 20, 1964, Mexico City

Work composed: originally the final movement of Altar de Muertos, a string quartet written for and commissioned by the Kronos Quartet in 1996-97. Arranged for string orchestra in 2021

World premiere: John Adams led the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra at Libbey Bowl in Ojai, CA, on September 19, 2021.

Instrumentation: string orchestra

Estimated duration: 10 minutes

Born into a musical family, Gabriela Ortiz has always felt she didn’t choose music – music chose her. Her parents were founding members of the group Los Folkloristas, a renowned music ensemble dedicated to performing Latin American folk music. Growing up in cosmopolitan Mexico City, Ortiz’s music education was multifaceted; she played charango and guitar with Los Folkloristas while also studying classical piano. Later, Ortiz was mentored in composition by renowned Mexican composers Mario Lavista, Julio Estrada, Federico Ibarra, and Daniel Catán. Ortiz continued her studies in Europe, earning a doctorate in composition and electronic music from London’s City University under the guidance of Simon Emmerson.

Ortiz’s music incorporates seemingly disparate musical worlds, from traditional and popular idioms to avant-garde techniques and multimedia works. This is, perhaps, the most salient characteristic of her oeuvre: an ingenious merging of distinct sonic worlds. While Ortiz continues to draw inspiration from Mexican subjects, she is interested in composing music that speaks to international audiences.

Conductor Gustavo Dudamel, a longtime champion of Ortiz’s music, stated: “Gabriela is one of the most talented composers in the world – not only in Mexico, not only in our continent – in the world. Her ability to bring colors, to bring rhythm and harmonies that connect with you is something beautiful, something unique.” Under Dudamel’s direction, the Los Angeles Philharmonic has commissioned and premiered seven works by Ortiz in recent years, including her ballet Revolución diamantina (2023), her violin concerto Altar de Cuerda (2021), and Kauyumari (2021) for orchestra. These three works are featured on the album Revolución diamantina, which was released in June 2024.

La Calaca began as the final movement of Altar de Muertos (Altar of the Dead), a string quartet commissioned by the Kronos Quartet. Altar de Muertos reflects the traditions and festivities of the Day of the Dead. Ortiz writes, “The tradition of the Day of the Dead festivities in Mexico is the source of inspiration for the creation of a work for string quartet whose ideas could reflect the internal search between the real and the magic, a duality always present in Mexican culture, from the past to this present.”

Each movement of Altar embodies the “diverse moods, traditions and the spiritual worlds which shape the global concept of death in Mexico, plus my own personal concept of death,” Ortiz explains. In La Calaca, the music expresses “Syncretism [in religion, the practice of merging beliefs and rituals from disparate traditions] and the concept of death in modern Mexico, chaos and the richness of multiple symbols, where the duality of life is always present: sacred and profane; good and evil; night and day; joy and sorrow. This movement reflects a musical world full of joy, vitality, and a great expressive force. At the end of La Calaca I decided to quote a melody of Huichol origin, which attracted me when I first heard it. That melody was sung by Familia de la Cruz. The Huichol culture lives in the State of Nayarit, Mexico. Their musical art is always found in ceremonial and ritual life.”

The Four Seasons Mixtape

“A mixtape, harkening back to the days of holding a cassette recorder up to the radio, has come into the modern lexicon as a compilation of different musical selections, often from different artists or composers, and usually evoking some similar mood or subject matter,” writes Modesto Symphony Orchestra’s Music Director Nicholas Hersh. “In fact, Vivaldi’s Four Seasons is perhaps an early representation of this concept: a set of four violin concerti, each of which can be performed separately, but when taken together they form a greater narrative. Our MSO ‘Four Seasons Mixtape’ takes this a step further by assigning each season to a different composer. Vivaldi’s original Summer sets the tone, and Max Richter’s Autumn [Recomposed] follows it up with a ‘remix’ of the Baroque sound with modern harmony and syncopation. Belgian violin virtuoso Eugene Ysaÿe’s Wintersong imparts a Romantic sumptuousness to an otherwise bleak season, and finally Astor Piazzolla takes us home with his uproarious Buenos Aires Spring, infused with the rhythms of the Tango.

“It is no easy feat to perform such wildly different musical styles as part of the same whole, and I am so grateful to Audrey Wright for realizing this Mixtape with us!”

Antonio Vivaldi

“L’estate” (Summer) from The Four Seasons for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 8 No 2

Composer: born March 4, 1678, Venice; died July 27/28, 1741, Vienna

Work composed: published 1725. Dedicated to Count Wenceslas Morzin.

World premiere: undocumented

Instrumentation: solo violin, continuo, and strings

Estimated duration: 11.5 minutes

Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons are some of the most recognizable and most performed Baroque works ever written. They have also been used by numerous companies to sell products, from diamonds to high-end cars to computers. With that level of exposure, it is easy to assume we “know” The Four Seasons, but there is more to these concertos than meets the eye, or the ear.

The Four Seasons are part of a larger collection of concertos Vivaldi titled Il cimento dell’armonia e dell’inventione (The contest between harmony and invention). Each concerto is accompanied by a sonnet, possibly written by Vivaldi himself, which gives specific descriptions of the music as it unfolds.

Summer’s slow introduction evokes a hot, humid summer day: “Under the merciless summer sun languishes man and flock; the pine tree burns … ” Lethargic birdcalls are abruptly interrupted by violent thunderstorms. In the slow movement, the soloist (shepherd) cries out in fear for his flock in the blistering heat. While he laments, the ensemble becomes buzzing flies. The final movement morphs into a tremendous hailstorm that destroys the crops.

Max Richter

“Autumn” from The Four Seasons Recomposed

Composer: born March 22, 1966, Hamelin, Lower Saxony, West Germany

Work composed: 2011-12

World premiere: André de Ridder led the Britten Sinfonietta with violinist Daniel Hope at the Barbican Centre on October 31, 2012, in London.

Instrumentation: solo violin and strings

Estimated duration: 8 minutes

Max Richter’s fusion of classical music and electronic technology, as heard in his genre-defining solo albums and numerous scores for film, TV, dance, art, and fashion, has blazed a trail for a generation of musicians.

In 2011, the recording label Deutsche Grammophon invited Richter to join its acclaimed Recomposed series, in which contemporary artists are invited to re-work a traditional piece of music. Richter chose Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons. In a 2014 interview with the website Classic FM, Richter explained, “When I was a young child I fell in love with Vivaldi’s original, but over the years, hearing it principally in shopping centres, advertising jingles, on telephone hold systems and similar places, I stopped being able to hear it as music; it had become an irritant – much to my dismay! So I set out to try to find a new way to engage with this wonderful material, by writing through it anew – similarly to how scribes once illuminated manuscripts – and thus rediscovering it for myself. I deliberately didn’t want to give it a modernist imprint but to remain in sympathy and in keeping with Vivaldi’s own musical language.”

“ … The key thing for me to figure out when navigating through this material was just how much Vivaldi and how much me was happening at any point,” Richter continued. “Three quarters of the notes in the new score are mine, but that is not the whole story. Vivaldi’s DNA is omnipresent in the work, and trying to take that into account at all times was the key challenge for me.”

Richter’s version of “Autumn” inserts syncopations (rhythmic off-beats) and subtle electronics into Vivaldi’s original music; the overall effect blurs the boundaries between which phrases are Vivaldi’s and which are Richter’s to a remarkable degree. “I’ve used electronics in several movements, subtle, almost inaudible things to do with the bass,” says Richter, “but I wanted certain moments to connect to the whole electronic universe that is so much part of our musical language today.”

During the recording sessions for Richter’s Recomposed Four Seasons, the composer adds, “In the second movement of ‘Autumn,’ I asked the harpsichordist Raphael Alpermann to play in what is a rather old-fashioned way, very regularly, rather like a ticking clock. That was partly because I didn’t want the harpsichord part to be attention-seeking, but also because that style connects to various pop records from the 1970s where the harpsichord or Clavinet was featured, including various Beach Boys albums and the Beatles’ Abbey Road.”

Eugène Ysaÿe

Chant d’hiver (Winter Song)

Composer: born July 16, 1858, Liège, Belgium; died May 12, 1931, Liège

Work composed: 1902

World premiere: undocumented

Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 12.5 minutes

Known during his lifetime as “The King of the Violin,” Eugène Ysaÿe was also a noted composer and conductor. Born 18 years after the death of the legendary Italian violinist Niccolò Paganini, the Belgian virtuoso was – and is – widely considered the greatest violinist of his time. This opinion was shared by the foremost composers of the latter 19th – and early 20th-century, including Claude Debussy, Ernest Chausson, Gabriel Faurè, and fellow Belgian César Franck, all of whom dedicated works to Ysaÿe.

Ysaÿe’s Chant d’hiver was inspired by a famous poem from medieval French poet François Villon (c.1431-after 1463). The poem, known in English as “Ballad of the Ladies of Bygone Times,” features a wistful refrain, “But where are the snows of yesteryear?” The exquisite melancholy of the soloist’s long phrases and the orchestra’s deft accompaniment evoke an air of longing – and also captures the quintessentially Romantic situation in which one is sad while simultaneously finding an odd pleasure in it.

Astor Piazzolla

“Primavera porteña” from Cuatro estaciones porteñas de Buenos Aires (“Spring” from The Four Seasons of Buenos Aires)

Composer: born March 11, 1921, Mar del Plata, Argentina; died July 5, 1992, Buenos Aires

Work composed: Piazzolla originally composed the Cuatro estaciones porteñas de Buenos Aires for Melenita de oro, a play by his countryman, Alberto Rodríguez Muñoz. The movements were written individually, between the years 1965 -1970, and Piazzolla did not originally intend them to be performed as a single work. The original version of Cuatro estaciones is scored for Piazzolla’s quintet, which consisted of violin, electric guitar, piano, bass, and bandóneon (a large button accordion). Tonight’s arrangement, for solo violin and string orchestra, was created in 1999 by Leonid Desyatnikov for violinist Gidon Kremer.

World premiere: Piazzolla and his quintet played the Cuatro estaciones for the first time at the Teatro Regina in Buenos Aires, on May 19, 1970.

Instrumentation: solo violin and strings

Estimated duration: 5 minutes

“For me, tango was always for the ear rather than the feet.” – Astor Piazzolla

Astor Piazzolla and tango are inseparably linked. He took a dance from the back rooms of Argentinean brothels and blurred the lines between popular and “art” music to such an extent that such categories no longer apply.

In the mid-1950s, Piazzolla went to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger, one of the 20th century’s most renowned composition teachers. She was unimpressed with the scores he showed her but, after insisting he play her some of his own tangos, she declared, “Astor, this is beautiful. I like it a lot. Here is the true Piazzolla – do not ever leave him.” Piazzolla later called this “the great revelation of my musical life,” and followed Boulanger’s advice. He took tango’s raw passion and fire, with its powerful rhythms and edgy melodies, and made it an essential part of classical repertoire.

The version of the Cuatro estaciones porteñas de Buenos Aires heard on tonight’s program was created in 1999 by Russian composer/arranger Leonid Desyatnikov, at the request of violinist Gidon Kremer. Desyatnikov not only arranged Cuatro estaciones, but also inserted quotes from Antonio Vivaldi’s Four Seasons into Piazzolla’s music.

Tango’s musical style requires several string techniques not often heard in classical music: wailing glissandos, sharp pizzicatos that threaten to break strings, bouncing harmonics and, in particular, a harsh, scratchy, distinctly “un-pretty” manner of bowing, sometimes using the wood, rather than the hair, of the bow.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

Branford Marsalis with the Modesto Symphony Orchestra

October 5, 2024 at 7:00 pm

VISIT MOBILE PROGRAM →

READ OUR PROGRAM NOTES →

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE VERSION →

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Branford Marsalis with the Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Saturday, October 5, 2024 at 7:30 pm

Gallo Center for the Arts, Mary Stuart Rogers Theater

Nicholas Hersh, conductor

Branford Marsalis, alto saxophone

Program

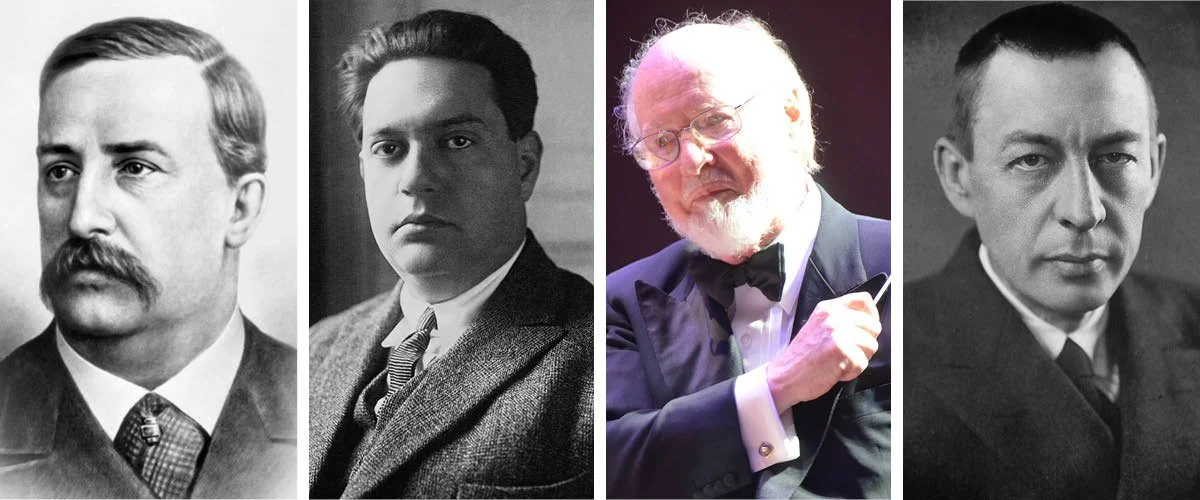

Alexander Borodin (1833-1887)

Polovtsian Dances from Prince Igor (1890)

Darius Milhaud (1892-1974)

Scaramouche, Op. 165c (1937)

Branford Marsalis, saxophone

i.Vif

ii.Modéré

iii.Brazileira

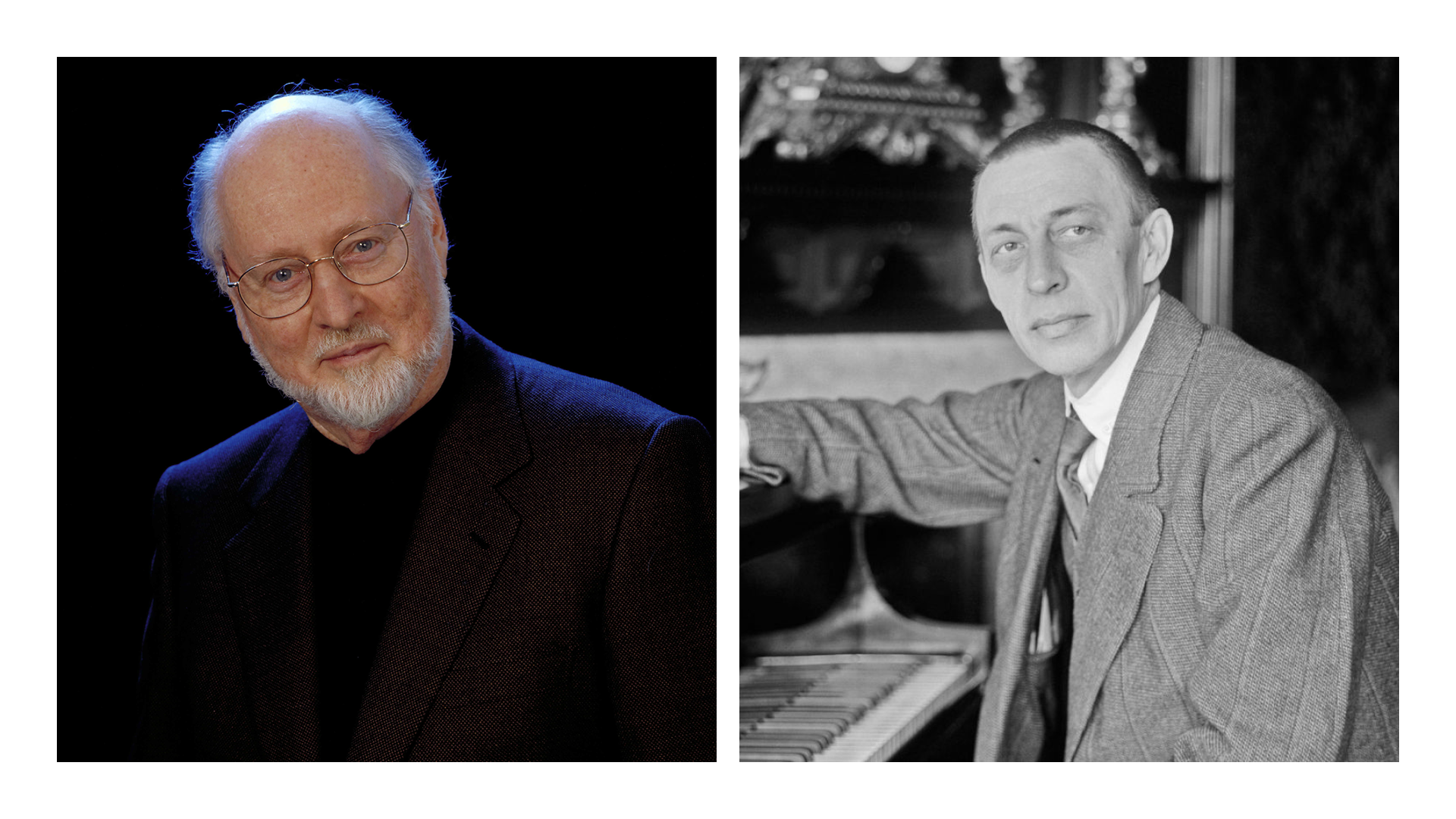

John Williams (b. 1932)

Escapades from Catch Me If You Can (1937)

Branford Marsalis, saxophone

1.Closing In

2.Reflections

3.Joy Ride

- INTERMISSION -

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943)

Symphonic Dances, Op. 45 (1940)

i.(Non) allegro

ii.Andante con moto (Tempo di valse)

iii.Lento assai — Allegro vivace

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Program Notes: Branford Marsalis with the Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Notes about:

Borodin's “Polovtsian Dances” from Prince Igor

Milhaud’s Scaramouche, Op. 165

Williams' “Escapades” from Catch Me If You Can

Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances for Large Orchestra, Op. 45

Program Notes for october 5th, 2024

Branford Marsalis with the

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Alexander Borodin

“Polovtsian Dances” from Prince Igor

Composer: born November 12, 1833, St. Petersburg; died February 27, 1887, St. Petersburg

Work composed: Borodin worked on Prince Igor from 1869-1874 and intermittently thereafter, but it remained uncompleted at the time of his death. Borodin’s friend and colleague, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, orchestrated the Polovtsian Dances.

World premiere: Eduard Nápravnik led the first performance of Prince Igor on November 16, 1890, at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg

Instrumentation: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes (1 doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, glockenspiel, snare drum, suspended cymbal, tambourine, triangle, harp, and strings

Estimated duration: 14 minutes

Alexander Borodin, like the other members of the Kucha, or Mighty Five, wrote music in his spare time. (A music critic coined the nickname “The Kucha” in reference to a group of influential 19th century Russian composers based in St. Petersburg. In addition to Borodin, the group included Mily Balakirev, César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov). A chemist by profession, Borodin made significant contributions to both his profession and his avocation.

The Kucha aspired to create authentically Russian music, free from the domination of German aesthetics. To this end, the Kucha featured indigenous folk songs and dances from different regions of the Russian empire.

Borodin employed folk dance tunes most effectively in his unfinished opera Prince Igor, the tale of 12th-century prince Igor Sviatoslavich’s failed attempt to stop the invasion of the Polovtsian Tatars in 1185. In the opera’s second act, Igor and his son are captured and held in the Polovtsian military camp. To pass the time, the Polovtsians sing and dance for the captive Russians.

The opera Prince Igor has had a fitful performance history, but the ballet sequence known as the “Polovtsian Dances” quickly became a stand-alone orchestral piece, and Borodin’s most popular and most performed music.

In 1953, the Tony award-winning musical Kismet debuted on Broadway; two years later, MGM adapted it for film. Much of the music from Kismet was derived from Borodin’s music, including the “Polovtsian Dances,” and both musical and film versions introduced Borodin to new audiences. One of Borodin’s most unforgettable melodies became Kismet’s signature hit song, “Stranger in Paradise.”

Darius Milhaud

Scaramouche, Op. 165

Composer: born September 4, 1892, Marseilles; died June 22, 1974, Geneva

Work composed: 1935-37. Originally written for two pianos. Milhaud subsequently arranged Scaramouche for alto saxophone and orchestra. At Benny Goodman’s request, Milhaud also produced a version for clarinet and orchestra.

World premiere: 1937, at the Paris International Exposition.

Instrumentation: solo alto saxophone, 2 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, bass drum, castanets, cymbals, snare drum, and strings

Estimated duration: 11 minutes

In 1937, French pianist Marguerite Long asked her friend and colleague Darius Milhaud to compose a two-piano duet for her students to perform at the Paris International Exposition. Milhaud complied, repurposing some music he had written for a production of Moliere’s play Le médecin volant (The Flying Doctor) for the first and third movements. The central slow section of Scaramouche is another recycled work, an overture Milhaud wrote in 1936 for a French play based on the life of Simón Bolívar. (Milhaud, fascinated by the life of the man South Americans nicknamed “El Libertador,” also made Bolívar the subject of his third opera. However, none of the music Milhaud wrote for the play, including the excerpt that became the second movement of Scaramouche, ended up in the opera).

Scaramouche, one of the central characters from Renaissance Italy’s Commedia dell’arte, is most often portrayed as clown who specializes in pranks. Although the music for Milhaud’s Scaramouche derives from previously composed works, the ebullience and merriment of Scaramouche’s character permeates the music, particularly the final movement, in which infectious Brazilian samba rhythms support a delightfully cheeky melody.

Composers are not always the best judges of their own work. Camille Saint-Saëns refused to allow Carnival of the Animals to be published during his lifetime, because he didn’t want his reputation as a serious composer tarnished by what he considered a musical trifle. Today, of course, Carnival of the Animals is Saint-Saëns’ most performed and best-known works, and it has been delighting audiences for more than 100 years. Similarly, Milhaud thought little of Scaramouche, and urged his publisher to ignore it. Fortunately, the publisher did not listen to his client, and Scaramouche became immensely popular. Today it is one of the most-performed piano duets in the repertoire, and its many arrangements for soloist and orchestra attest to its enduring charm.

John Williams

“Escapades” from Catch Me If You Can

Composer: born February 8, 1932, Flushing, Queens

Work composed: 2002

World premiere: The film Catch Me If You Can with Williams’ score premiered on December 25, 2002

Instrumentation: 3 flutes, 2 oboes, 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 2 trombones, bass trombone, tuba, timpani, percussion, piano/celeste, harp, and strings

Estimated duration: 13 minutes

John Williams is synonymous with movie music. He became a household name with the Academy Award-winning score he wrote in 1977 for Star Wars, and he has defined the symphonic Hollywood sound ever since.

Over his career, Williams has garnered a record 54 Oscar nominations for Best Original Score, including the one he wrote for longtime collaborator Steven Spielberg’s 2002 film, Catch Me If You Can. The movie is based on Frank Abagnale’s eponymous autobiography, which details his criminal activities during the 1960s, as well as the FBI’s years-long campaign to apprehend him. Over seven years, Abagnale impersonated an airline pilot, a doctor, and a public prosecutor in the course of his successful efforts as a master conman and forger.

“The film is set in the now nostalgically tinged 1960s,” Williams writes about his music, “and so it seemed to me that I might evoke the atmosphere of that time by writing a sort of impressionistic memoir of the progressive jazz movement that was then so popular. The alto saxophone seemed the ideal vehicle for this expression ... “In ‘Closing In,’ we have music that relates to the often-humorous sleuthing which took place in the story, followed by ‘Reflections,’ which refers to the fragile relationships in Abnagale’s family. Finally, in ‘Joy Ride,’ we have the music that accompanies Frank’s wild flights of fantasy that took him all over the world before the law finally reined him in.”

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Symphonic Dances for Large Orchestra, Op. 45

Composer: born April 1, 1873, Oneg, Russia; died March 28, 1943, Beverly Hills, CA

Work composed: the summer and autumn of 1940. The published score bears the inscription: “Dedicated to Eugene Ormandy and The Philadelphia Orchestra.”

World premiere: Eugene Ormandy led the Philadelphia Orchestra on January 3, 1941

Instrumentation: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, alto saxophone, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, chimes, cymbals, drum, orchestra bells, tam-tam, tambourine, triangle, xylophone, piano, harp, and strings

Estimated duration: 35 minutes

Sergei Rachmaninoff had great regard for the Philadelphia Orchestra and its music director, Eugene Ormandy. As a pianist, he had performed with them on several occasions, and as a composer, he appreciated the full rich sound Ormandy and his musicians produced. Sometime during the 1930s, Rachmaninoff remarked that he always had the unique sound of this ensemble in his head while he was composing orchestral music: “[I would] rather perform with the Philadelphia Orchestra than any other of the world.” When Rachmaninoff began working on the Symphonic Dances, he wrote with Ormandy and the orchestra in mind. Several of Rachmaninoff’s other orchestral works, including the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini and the Piano Concerto No. 4, were also either written for or first performed by Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra.

The Symphonic Dances turned out to be Rachmaninoff’s final composition. Although not as well-known as the piano concertos or the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Rachmaninoff himself and many others regard the Symphonic Dances as his greatest orchestral work. “I don’t know how it happened,” the composer remarked. “It must have been my last spark.”

Nervous pulsing violins open the Allegro, over which the winds mutter a descending minor triad (three-note chord). The strings set a quickstep tempo, while the opening triad becomes both the melodic and harmonic foundation of the movement as it is repeated, reversed and otherwise developed. The introspective middle section features the first substantial melody, sounded by a distinctively melancholy alto saxophone. The Allegro concludes with a return of the agitated quickstep and fluttering triad.

Muted trumpets and pizzicato strings open the Andante con moto with a lopsided stuttering waltz, followed by a subdued violin solo. This main theme has none of the Viennese lightness of a Strauss waltz; its haunting, ghostly quality borders on the macabre suggestive of Sibelius’ Valse triste or Ravel’s eerie La valse. Rachmaninoff’s waltz is periodically interrupted by sinister blasts from the brasses.

In the Lento assai: Allegro vivace, Rachmaninoff borrows the melody of the Dies irae (Day of Wrath) from the requiem mass. Rachmaninoff had used this iconic melody many times before, most notably in Isle of the Dead and the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. In the Symphonic Dances, the distinctive descending line has even more suggestive power; we can hear it as Rachmaninoff’s final statement about the end of his compositional career. This movement is the most sweeping and symphonic of the three and employs all the orchestra’s sounds, moods, and colors. In addition to the Dies irae, Rachmaninoff also incorporates other melodies from the Russian Orthodox liturgy, including the song “Blagosloven Yesi, Gospodi,” describing Christ’s resurrection, from Rachmaninoff's choral masterpiece, All-Night Vigil.

On the final page of the Symphonic Dances manuscript, Rachmaninoff wrote, “I thank Thee, Lord!”

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

Star Wars: Return of the Jedi

May 31, 2024 at 7:30 pm

June 1, 2024 at 2:00 pm

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back in Concert

Friday, May 31, 2024 at 7:30 pm

Saturday, June 1, 2024 at 2:00 pm

Gallo Center for the Arts, Mary Stuart Rogers Theater

John Williams (b. 1932)

Star Wars: Return of the Jedi in Concert

Feature Film with Orchestra

There will be one intermission.

Presentation licensed by Disney Concerts in association with 20th Century Fox, Lucasfilm Ltd., and Warner/Chappell Music. All rights reserved.

Star Wars Film Concert Series

Star Wars: Return of the Jedi

Twentieth Century Fox Presents

A Lucasfilm Ltd. production

Starring

Mark Hamill

Harrison Ford

Carrie Fisher

Billy Dee Williams

Anthony Daniels as C-3PO

Co-Starring

David Prowse

Kenny Baker

Peter Mayhew

Frank Oz

Directed by

Richard Marquand

Produced by

Howard Kazanjian

Screenplay by

Lawrence Kasdan and George Lucas

Story by

George Lucas

Executive Producer

George Lucas

Music by

John Williams

Original Motion Picture Soundtrack available at Disneymusicemporium.com

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “JEDI” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

MSYO Season Finale

May 11, 2024 at 2 pm

Modesto Symphony Youth Orchestra

Season Finale Concert

Program

Concert Orchestra

Donald C. Grishaw, conductor

Antonin Dvorak (1841-1904) arr. Meyer

New World Symphony

iv. Finale

Georges Bizet (1838-1875) arr. Meyer

Habanera from Carmen

Klaus Badelt (b. 1967) arr. Ricketts

Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl

Percussion Ensemble

Ella webb, coach

Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) arr. Marlatt

St. Anthony Chorale

Traditional arr. Ostling

Sourwood Mountain

Percussion Ensemble

Joel Maki, coach

Nathan Daughtrey

On the Spectrum

Intermission

Symphony Orchestra

Elisha wells, conductor

Pascual Marquina (1873-1948) arr. Albert Wang

Espana Cani

Michael Giacchino (b. 1967) arr. James Kazik

Remember Me (from Coco)

Edvard Grieg(1843-1907) arr. Victor Lopez

The Holberg Suite

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Violin Concerto in A major, K. 219, No. 5

i. Allegro Aperto

Samuel Kraus, violin - 2023-2024 MSYO Concerto Competition Winner

A carmen celebration

Georges Bizet (1838-1875) arr. J. Bullock

Carmen Suite for Orchestra

ii. La Garde Montante from Act II

Georges Bizet (1838-1875) arr. E. Guiraud

Chanson du Toreador

Escamillo’s introduction and aria from Act II

Georges Bizet (1838-1875) arr. J. Bullock

Carmen Suite for Orchestra

iv. Danse Boheme, entr’act to Act II

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Beethoven's Symphony No. 9

May 10 & 11, 2024 at 7:30 pm

VISIT MOBILE PROGRAM →

READ OUR PROGRAM NOTES →

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE VERSION →

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9

Friday, May 10, 2024 at 7:30 pm

Saturday, May 11, 2024 at 7:30 pm

Gallo Center for the Arts, Mary Stuart Rogers Theater

Nicholas Hersh, conductor

MSO Chorus

Daniel R. Afonso Jr., chorus director

Georgiana Adams, soprano

Kindra Scharich, mezzo-soprano

Alex Boyer, tenor

Matt Boehler, bass

Program

Arvo Pärt (b. 1935)

Fratres (1977)

Amy Beach (1867-1944)

Peace I Leave With You (1891)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Symphony No. 9 in D minor (1824)

i.Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso

ii.Molto Vivace—Presto

iii.Adagio molto e cantabile

iv.Finale—Ode to Joy

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Program Notes: Beethoven's Symphony No. 9

Notes about:

Pärt’s Fratres

Beach’s Peace I Leave With You

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 “Choral”

Program Notes for MAy 10 & 11, 2024

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9

Arvo pärt

Fratres

Composer: born September 11, 1935, Paide, Estonia

Work composed: 1977

World premiere: undocumented

Instrumentation: string orchestra

Estimated duration: 6 minutes

The crystalline quality of Arvo Pärt’s music evokes the wintry climate of his native Estonia. Pärt achieves this shimmering transparency through single notes, a compositional style he named “tintinnabulation,” Latin for “little bells.” Pärt explains, “I have discovered that it is enough when a single note is beautifully played. This one note, or a silent beat, or a moment of silence, comforts me. I work with very few elements – with one voice, two voices. I build with primitive materials – with the triad, with one specific tonality. The three notes of a triad are like bells, and that is why I call it tintinnabulation.”

At the time Pärt composed Fratres, he was also immersing himself in the sound world of medieval and Renaissance music. Music from these periods did not often indicate which instruments or voice parts should be used, a practice Pärt employed with Fratres. This choice showcases notes and melodic phrases, rather than particular timbres, or sound colors.

Fratres features a series of variations on a simple stepwise theme, which reappears in several different octaves. Underneath the gently shimmering variations, the low strings maintain a steady drone. The overall effect is meditative, enveloping the listener in a mood of reflection.

AMy BEach

Peace I Leave With You

Composer: born September 5, 1867, Henniker, NH; died December 27, 1944, New York City

Work composed: 1891

World premiere: undocumented

Instrumentation: a cappella SATB chorus

Estimated duration: 1.5 minutes

Amy Beach’s musical accomplishments include several firsts: the first American woman to compose and publish a symphony – and the first American woman to have a symphony performed. She is also one of the first American composers – of any gender – whose musical training occurred wholly within the United States, rather than Europe. As such, Beach’s approach to composition and her aesthetics are uniquely American, and she did not measure the quality of her work by comparing it to music by European composers, unlike some of her contemporaries.

Beach’s prodigal musicality emerged as early as age two, as documented by her mother Clara: “Her gift for composition showed itself in babyhood before two years of age. She could, when being rocked to sleep in my arms, improvise a perfectly correct alto to any soprano air I might sing … She played the piano at four years, memorizing everything that she heard correctly ...” Clara was Beach’s first piano teacher; the young girl later studied piano in Boston. By the time she reached age 12, Beach’s parents were being lobbied by musical impresarios eager to launch their wunderkind daughter onto the concert stage. Beach’s parents declined, allowing Beach to refine her piano skills and pursue other musical studies through her teenage years. She made her concert debut at age 16, to great acclaim, and continued concertizing for the next two years, until her marriage to Dr. Henry Harris Aubrey Beach, 25 years her senior.

In 1930, Beach moved to New York, where she formed a close relationship with St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church, and wrote many liturgical choral works for their choir. It is likely her 1891 anthem, “Peace I Leave with You,” with text from the Gospel of John, was first sung there. The simple elegance of Beach’s homophonic setting emphasizes the clarity and meaning of the words to create a gentle benediction.

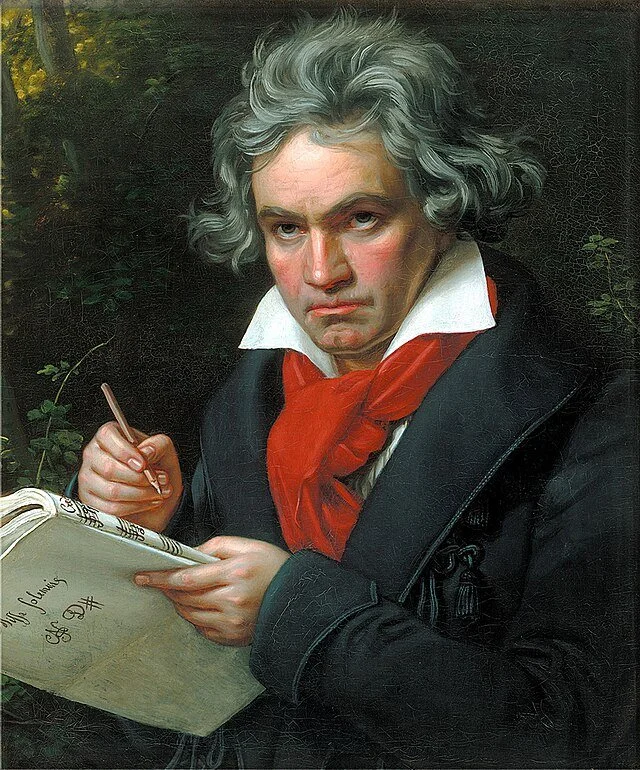

ludwig van beethoven

Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 “Choral”

Composer: born December 16, 1770, Bonn, Germany; died March 26, 1827, Vienna

Work composed: Beethoven made preliminary sketches in 1817-18, but most of the music was composed between 1822–24. Beethoven finished his Ninth Symphony in February 1824, and dedicated it to King Frederick William III of Prussia.

World premiere: Beethoven conducted the first performance on May 7, 1824, at the Kärntnerthor Theater in Vienna.

Instrumentation: soprano, alto, tenor, and bass soloists, four-part mixed chorus, piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, bass drum, cymbals triangle and strings.

Estimated duration: 70 minutes

The Ninth Symphony extends beyond the realm of the concert hall and has permeated Western culture on many levels, including socio-political and commercial arenas. The music of the Ninth, particularly the “Ode to Joy” melody of the final movement, is so familiar to us that it has lost its unique character and taken on the quality of folk music; that is, it has shed its “composed” identity as a melody written by Ludwig van Beethoven and simply exists within the communal ear of our collective consciousness.

While some classical works are inextricably linked to the time in which they were written, Beethoven’s profound musical statements about freedom, equality, and humanity resonate just as powerfully today as they did at the Ninth’s premiere. This was evident to the entire world 35 years ago, when Leonard Bernstein conducted an international assembly of instrumentalists and singers in a historic performance of Beethoven’s Ninth at East Berlin’s Schauspielhaus (now Konzerthaus) on December 22, 1989, three days after the fall of the Berlin Wall. To emphasize the historic event, Bernstein substituted the word “freedom” for “joy” in the famous lyrics by the poet Friedrich Schiller in the final movement. The performance was broadcast on television worldwide, attracting more than 200 million viewers.

By 1822, Beethoven was completely deaf and emotionally isolated. Five years earlier, at the age of 47, he had written in his journal, “Before my departure for the Elysian fields I must leave behind me what the Eternal Spirit has infused into my soul and bids me complete.” Alone and embittered, Beethoven focused almost exclusively on his musical legacy.

The lofty salute to the human spirit expressed in Schiller’s poem An die Freude (To Joy) had resonated with Beethoven for many years; in 1790 he set a few lines in a cantata written to commemorate the death of Emperor Leopold II; he also included portions of Schiller’s poem in his opera Fidelio. “The search for a way to express joy,” as Beethoven described it, was the subject of his final symphony. To that end, Beethoven edited and arranged Schiller’s lines to suit his musical and dramatic needs, using a melody from the Choral Fantasy he had written 20 years earlier.

The symphony opens with the strings sounding a series of hollow open chords, neither major nor minor, which are harmonically ambiguous – what key is this? The fifths build into a massive statement featuring a weighty dotted rhythmic theme. The intensity of this movement foreshadows the finale.

As was his wont, Beethoven broke with symphonic convention by writing a second-movement scherzo. The music bursts forth with dramatic string octaves and pounding timpani. The main theme, a contrapuntal fugue, gives way to a demure wind melody. Underneath its playful simplicity, the barely contained agitation of the scherzo pulses in the strings, like a racehorse pawing at the starting gate.

In a symphony synonymous with innovation, Beethoven’s most significant departure from convention is the inclusion, for the first time, of a chorus and vocal soloists in a formerly exclusively instrumental genre. The cellos and basses play an instrumental recitative, later sung by the baritone, which is followed by the unaccompanied “Joy” melody. Beethoven then presents several instrumental variations, including a triumphal brass fanfare. The baritone soloist introduces Schiller’s poem with words of Beethoven’s: “O friends, not these tones; instead, let us strike up more pleasing and joyful ones.” The chorus repeats the last four lines of each stanza as a refrain, followed by the vocal quartet. A famous interlude, the Turkish March, follows (this music was considered “Turkish” because of the inclusion of the triangle, cymbals and bass drum, exotic additions to the orchestra of Beethoven’s time). After a number of variations, the chorus returns with a monumental concluding double fugue.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto

April 12 & 13, 2024 at 7:30 pm

VISIT MOBILE PROGRAM →

READ OUR PROGRAM NOTES →

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE VERSION (pdf, 3mb) →

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto

Friday, April 12, 2024 at 7:30 pm

Saturday, April 13, 2024 at 7:30 pm

Gallo Center for the Arts, Mary Stuart Rogers Theater

Nicholas Hersh, conductor

Tai Murray, violin

Program

Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992)

Tangazo (Variations on Buenos Aires) (1969)

Louise Farrenc (1804-1875)

Symphony No. 3 in G minor (1847)

i.Adagio—Allegro

ii.Adagio cantabile

iii.Scherzo: Vivace

iv.Finale: Allegro

- INTERMISSION -

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) arr. Nicholas Hersh

Fugue in G minor BWV 578 “Little Fugue” (1918)

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847)

Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 (1844)

Tai Murray, violin

i.Allegro molto appassionato

ii.Andante

iii.Allegretto non troppo—Allegro molto vivace

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Program Notes: Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto

Notes about:

Piazzolla’s Tangazo (Variations on Buenos Aires)

Farrenc’s Symphony No. 3 in G minor

Bach’s Fugue in G minor BWV 578 “Little Fugue”

Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64

Program Notes for April 12 & 13, 2024

Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto

Astor piazzolla

Tangazo (Variations on Buenos Aires)

Composer: born March 11, 1921, Mar del Plata, Argentina; died July 5, 1992, Buenos Aires

Work composed: 1969

World premiere: 1970 in Washington, D.C., by the Ensemble Musical de Buenos Aires

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, cymbals, glockenspiel, guiro, tom-toms, triangle, xylophone, piano, and strings

Estimated duration: 15 minutes

“For me, tango was always for the ear rather than the feet.” – Astor Piazzolla

Astor Piazzolla is inextricably linked with tango. He took a dance from the back rooms of Argentinean brothels and blurred the lines between popular and “art” music to such an extent that, in the case of his music, such categories no longer apply.

Tangazo is a later composition, originally scored for solo bandoneon, piano, and strings. Piazzolla was a master of the bandoneón, a small button accordion of German origin, which originally served as a portable church organ. The distinctive sound of the bandoneón became a fundamental element of Piazzolla’s tangos; its insouciance and melancholy permeate Piazzolla’s music, even in works scored for other instruments.

Tangazo begins in the low strings, which murmur a slow introduction with more than a hint of menace. Harmonically, Tangazo often ranges beyond conventional tango tonalities to explore a modernist palette replete with unexpected detours. After the deliberate legato pace of the introduction, a solo oboe takes off with a skittish tango full of bounce and swagger. Legato interludes featuring pensive horn solos alternate with the agitated tango. Overall, Tangazo conveys restlessness, even as its last notes fade away.

Louise farrenc

Symphony No. 3 in G minor

Composer: born May 31, 1804, Paris; died September 15, 1875, Paris

Work composed: 1847

World premiere: 1849, by the Orchestre de la Société des concerts du Conservatoire in Paris

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 33 minutes

During her lifetime, Louise Farrenc was well known as both a composer and outstanding pianist. Throughout the 19th century, she was also the first and only female professor of music on the faculty of the Paris Conservatory.

Farrenc grew up in a family of artists who encouraged their daughter’s musical interests. Young Louise displayed extraordinary talent at the piano in early childhood, and soon began composing her own music. When she was 15, her parents enrolled her at the Paris Conservatory to continue her composition studies, although she was tutored privately by its faculty because women were not admitted to the Conservatory’s composition program at the time..

At 18, Louise married a flutist, Aristede Farrenc, who later founded a music publishing house. By the 1830s, Farrenc was balancing a busy, multifaceted career as a teacher, composer, and pianist who concertized all over France. As a composer, Farrenc also began expanding her portfolio from solo piano music to larger forms such as symphonies, concert overtures, and a number chamber works, including piano quintets and trios. Farrenc, unlike many female composers whose music was discovered only long after their deaths, was able to hear the public performance of all three of her symphonies – which were well-reviewed – during her lifetime.

The symphonic format evolved from earlier German and Italian genres; by the mid-19th century, symphonies epitomized German style. In fervently nationalist France, particularly in Paris, symphonies and their composers faced aesthetic discrimination from those who deemed the symphony an exclusively German art form. Moreover, the idea of a woman writing symphonic music – in the eyes of some putting herself on par with symphonic greats such as Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Schubert, and others – seemed an outrageous provocation.

After a brief Adagio for winds, a graceful Allegro ensues, featuring themes in the strings. This opening movement is full of vigor, artful melodies, and a sense of orchestral mastery. Farrenc follows this confident beginning with a serene Adagio cantabile, featuring a solo clarinet soaring over low winds and brasses, suggesting the intimacy of a woodwind quintet. An agitated Scherzo follows, full of quicksilver flashes of light and shadow that showcases the upper winds. The Finale bristles with dramatic energy and features several powerful statements that unleash the strings’ fiery virtuosity with a series of scalar passages. Minor-key symphonies of this period usually conclude in their corresponding major key, but Farrenc maintains the G-minor intensity right up to the closing notes.

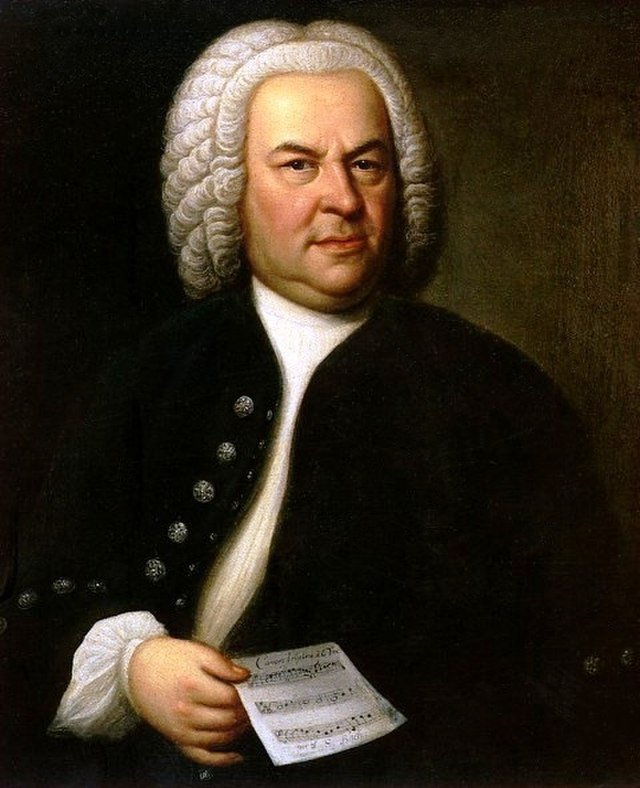

Johann Sebastian Bach

Fugue in G minor BWV 578 “Little Fugue” arr. Hersh

Composer: born March 21, 1685, Eisenach; died July 28, 1750, Leipzig

Work composed: c. 1703-07, written while Bach served as an organist in Arnstadt.

World premiere: undocumented

Instrumentation: flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, 2 horns, trumpet, chimes, vibraphone, and strings

Estimated duration: 3.5 minutes

Nicknames can be misleading. The only thing “little” about Johann Sebastian Bach’s Fugue in G minor, BWV 578, is its length. Just under four minutes long, this fugue features one of Bach’s best known and most recognizable fugue subjects, and it has been arranged for diverse ensembles, including Leopold Stowkowsi’s brass-heavy arrangement for full orchestra, and the Swingle Singers’ popular vocal jazz version.

Bach was renowned during his lifetime for his extraordinary ability to improvise at the keyboard. It is possible the distinctive fugue subject emerged first as an improvisation; at over four measures long, it is an unusually lengthy statement. Bach allows each voice to shine, including the basses (played by foot pedals on the organ). The opening three notes cut through the dense counterpoint, announcing the subject’s entrance clearly each time, as the music swirls and eddies towards a bold conclusion.

Felix Mendelssohn

Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64

Composer: born February 3, 1809, Hamburg; died November 4, 1847, Leipzig

Work composed: July 1838 – September 1844

World premiere: Niels Gade led the Gewandhaus Orchestra and violinist Ferdinand David in Leipzig on March 13, 1845

Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 27 minutes

“I would like to write a violin concerto for you next winter,” wrote Felix Mendelssohn to his longtime friend and colleague Ferdinand David in the summer of 1838. “There’s one in E minor in my head, and its opening won’t leave me in peace.” Mendelssohn, then conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, had known David for years. The two prodigies met as teenagers; 15-year-old David was a budding violin virtuoso and 16-year-old Mendelssohn had just completed his Octet for Strings. Years later, when Mendelssohn was appointed director of the Gewandhaus concerts in 1835, he hired David as concertmaster. In 1843, Mendelssohn founded the Leipzig Conservatory and quickly appointed David to the violin faculty.

Mendelssohn had played the violin since childhood, and by all accounts was quite accomplished. However, the E minor Violin Concerto required a level of technical knowledge and skill beyond Mendelssohn’s abilities, so he turned to David for hands-on advice. During the composition of the E minor Concerto, Mendelssohn wrote the melodies and designed the overall structure, while David served as technical consultant.

In this concerto, the violin is always and indisputably the star, while the orchestra’s role provides what the late music critic Michael Steinberg called “accompaniment, punctuation, scaffolding and a bit of cheerleading.” Music this familiar can be difficult to hear as a “composed” work at all; instead, it seems to emerge sui generis, like Athena bursting fully formed from the head of Zeus.

In a break with convention, the solo violin rather than the full orchestra opens the Allegro molto appassionato with the main theme. Mendelssohn also defied expectations by placing the first movement cadenza, which David composed, between the development and return of the main theme, rather than at the end of the movement.

A solo bassoon holds the last note of the Allegro and pivots without interruption to the Andante. Here the soloist leads with a lyrical, singing melody full of tender poignancy. The gentle Andante flows almost without pause into the Allegro molto vivace. The exuberant quicksilver theme of the finale contrasts sharply with the intimate Andante, and demands all the soloist’s technical and artistic skill.

Op. 64 turned out to be Mendelssohn’s last completed orchestral work; he died two years after its premiere. Scholar Thomas Grey observed, “It seems fitting, if fortuitous, that [the Violin Concerto] should combine one of his most serious and personal orchestral movements (the opening Allegro) with a nostalgic return to the world of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the finale – the world of Mendelssohn’s ‘enchanted youth’ and the music that, more than any other, epitomizes his contribution to the history of music.”

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

Symphonic Soundtrack

March 15 & 16, 2024 at 7:30 pm

VISIT MOBILE PROGRAM →

READ OUR PROGRAM NOTES →

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE VERSION (pdf, 1mb) →

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Symphonic Soundtrack

Friday, March 15, 2024 at 7:30 pm

Saturday, March 16, 2024 at 7:30 pm

Gallo Center for the Arts, Mary Stuart Rogers Theater

Nicholas Hersh, conductor

Rob Patterson, clarinet

Program

Giachino Rossini (1792-1868)

Overture to La Gazza Ladra (1817)

Giovanni Gabrieli (1554-1612)

Sonata pian’e forte (1597)

Jessie Montgomery (b. 1981)

Starburst (2012)

Aaron Copland (1900-1990)

Clarinet Concerto (1948)

Gabriel Faure (1845-1924)

Sicilienne from

Pelleas and Melisande Suite (1898)

Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)

Suite from The Firebird (1919)

John Williams (b. 1932)

Princess Leia’s Theme from Star Wars

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Program Notes: Symphonic Soundtrack

Notes about:

Rossini’s Overture to La Gazza Ladra

Gabrieli’s Sonata pian’e forte

Montgomery’s Starburst

Copland’s Clarinet Concerto

Faure’s Sicilienne from Pelleas and Melisande Suite

Stravinsky’s Suite from The Firebird

William’s Princess Leia’s Theme from Star Wars

Program Notes for March 15 & 16, 2024

Symphonic Soundtrack

Gioachino rossini (1792-1868)

Overture to La Gazza Ladra (1817)

This piece was chosen by violinist Josephine Gray

"Who Is the wittiest composer? Mozart, Rossini or perhaps Berlioz? My first memory of the Thieving Magpie overture during my early childhood in the UK was it being a musical joke as the opening drum roll caused the entire audience to spring to their feet, mistaking it for God Save the Queen! Rossini was undoubtedly a master entertainer and a musical tease, showing off the virtuoso winds and strings, and the pompous brass and percussion. He sure knew how to build momentum and excitement and has scored the magpie protagonist perfectly with lilting, graceful, cheeky and mischievous themes and masterful orchestration."

Giovanni gabrieli (1554-1612)

Sonata pian’e forte (1597)

This piece was chosen by principal viola, Patricia Whaley

In addition to the many philosophical and scientific advancements brought on by the Italian Renaissance, music also saw significant innovation, including a standardization of notation to something very close to what we would recognize in modern sheet music. The prolific Venetian composer Giovanni Gabrieli gave remarkably clear instructions to performers in his written music while he served as maestro of St. Mark’s Basilica, including, in the case of his 1597 Sonata pian’ e forte, which passages should be played forte (loud) and which piano (soft)—indications we still use today. In St. Mark’s, the musicians were traditionally split into two groups in choir lofts facing one another, and Gabrieli wrote much of his music with this layout in mind, making extensive use of echoes and call-and-response; today, we can recreate this almost 500-year-old style to great effect with brass instruments laid out in a similar “antiphonal choir” setup.*

*Program Notes written by Nicholas Hersh, music director

jessie montgomery (b. 1981)

Starburst (2012)

This piece was chosen by principal viola, Patricia Whaley

"I love Starburst! I hope you will too. It’s full of wonderfully bright, propulsive energy, and it shows off the wealth of different sounds and colors that strings alone can produce, using all the different techniques we have at our disposal. Jessie Montgomery, a violinist herself, writes in a style that’s both distinctly modern and still welcoming for all listeners, as well as being challenging but eminently playable for us."

aARON COPLAND (1900-1990)

Clarinet Concerto (1948)

This piece was chosen by violinist Josephine Gray

"I suggested this piece because my late father played jazz clarinet and saxophone.For me the first movement has a heart rending plaintiff quality that reaches my soul in a poignant and nostalgic way. It's not particularly sad, but just very human. Pain and hope, serenity coupled with disquiet as it goes in harmonic directions that are unexpected. After a cadenza bridge which introduces the jaunty theme of the second movement, Copland uses slap bass and Latin American jazz themes to set up a kind of musical race that's bright, intricate and overwhelmingly fun ending with a Gershwin "smear" flourish."

Gabriel faure (1845-1924)

Sicilienne from Pelleas and Melisande Suite (1948)

This piece was chosen by Don Grishaw, violin

"I first heard it when I was in fourth or fifth grade, on the radio... It's a magical piece with a beautiful melody."

The slow, symbolism-laden words of Belgian playwright Maurice Maeterlinck’s 1893 Pelléas and Mélisande never saw much success until the play was set to music—multiple times, by musical luminaries like Claude Debussy, Arnold Schoenberg, and Gabriel Fauré. Fauré used a light touch: the play was staged in an English translation and Fauré only added incidental music (music usually played only during scene changes or in the background). Matching the moody story of forbidden love, the most well-known segment of music is the “Sicilienne,” which accompanies Mélisande playing the flute for her lover Pelléas by a well, the gentle lilt to its rhythm in a dreamy 6/8 time adding an air of antiquity.*

*Program Notes written by Nicholas Hersh, music director

Igor stravinsky (1882-1971)

Suite from The Firebird (1919)

This piece was chosen by principal viola, Patricia Whaley

Igor Stravinsky was a 20th-century chameleon—he explored several different musical styles over the course of his nearly one-hundred-year life, from experiments in modernist atonal music to a conservative “neo-Classical” style. Russian by birth, he soared to fame (and scandal) in Paris with his late-Romantic, folk-infused Ballets Russes, which included the infamous Rite of Spring, so avant-garde that it allegedly started a riot at its premiere. Among his earlier successes in Paris was the 1910 ballet The Firebird, a retelling of an ancient folk tale of a young warrior-prince defeating a monstrous sorcerer with the help of a magic bird. The music is immensely evocative and a tour-de-force of orchestration, from the low strings depicting a shadowy forest, to the frenetic xylophone and trombone glissandos of the sorcerer’s wild minions, and finally to the majestic horn call that marks the hero’s victory over evil.*

*Program Notes written by Nicholas Hersh, music director

John williams (b. 1932)

Princess Leia’s Theme from Star Wars (1977)

This piece was chosen by music director, Nicholas Hersh

"This is really one of the first pieces of music that I would have heard as a kid that used the orchestra in a huge and engaging way, and watching Star Wars as a kid is a fundamental part of my upbringing. This music is written so beautifully by John Williams with this soaring, beautiful melody, which really left a mark on me and may have even set me down a path to become the conductor I am today. Performing Williams's musicis always such a privilege because he just knows how to write for the orchestra to make it sound its absolute best. Every instrument is involved. Every instrument gets an interesting line to play. In addition to hearing these lush harmonies and soaring melodies that we instantly associate with our favorite characters from Star Wars."

MSYO Spring Concert

February 10, 2024 at 2 pm

Modesto Symphony Youth Orchestra

Spring Concert

Program

Concert Orchestra

Donald C. Grishaw, conductor

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) arr. Meyer

Overture from The Magic Flute

Nikolai Rimski-Korsakov (1844-1908) arr. Meyer

Themes from Scheherazade

John Philip Sousa (1854-1960) arr. Isaac

Stars and Stripes Forever

Percussion Ensemble

Joe Frank Williams

Crystalized

Intermission

Symphony Orchestra

Ryan Murray, conductor

Victor Lopez (b. 1950)

Danza Africana

Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) arr. Stafford

Pas de Deux from The Nutcracker, Op. 71

Viviana Alfaro, harp

Bella Davila, cello

Jules Massenet (1842-1912)

Selections from Le Cid Suite

IV. Finale

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Gershwin's An American in Paris

February 9 & 10, 2024 at 7:30 pm

VISIT MOBILE PROGRAM →

READ OUR PROGRAM NOTES →

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE VERSION (pdf, 3mb) →

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Gershwin’s An American in Paris

Friday, February 9, 2024 at 7:30 pm

Saturday, February 10, 2024 at 7:30 pm

Gallo Center for the Arts, Mary Stuart Rogers Theater

Nicholas Hersh, conductor

Program

William L. Dawson (1899-1990)

Negro Folk Symphony (1934)

i.The Bond of Africa

ii.Hope in the Night

iii.O, Le’ Me Shine, Shine Like a Morning Star!

- INTERMISSION -

Lili Boulanger (1893-1918)

D’un Matin de Printemps (1918)

George Gershwin (1898-1937)

An American in Paris (1928)

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Program Notes: Gershwin's An American in Paris

Notes about:

Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony

Boulanger’s D’un Matin de Printemps

Gershwin’s An American in Paris

Program Notes for February 9 & 10, 2024

Gershwin’s An American in Paris

William dawson

Negro Folk Symphony

Composer: born September 26, 1899, Anniston, AL; died May 2, 1990, Montgomery, AL

Work composed: 1934, rev. 1952

World premiere: Leopold Stokowski led the Philadelphia Orchestra on November 20, 1934, at Carnegie Hall in New York City

Instrumentation: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, adawura (Ghanaian bell), African clave, bass drum, chimes, cymbals, gong, snare drum, tenor drum, xylophone, harp, and strings

Estimated duration: 30 minutes

“I’ve not tried to imitate Beethoven or Brahms, Franck or Ravel – but to be just myself, a Negro,” William Dawson remarked in a 1932 interview. “To me, the finest compliment that could be paid my symphony when it has its premiere is that it unmistakably is not the work of a white man. I want the audience to say: ‘Only a Negro could have written that.’”

Two years later, Leopold Stokowski led the New York Philharmonic in the premiere of Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony. Critics and audiences alike hailed it as a masterpiece. One reviewer declared it “the most distinctive and promising American symphonic proclamation which has so far been achieved,” and another enthused, “the immediate success of the symphony [did not] give rise to doubts as to its enduring qualities. One is eager to hear it again and yet again.” Given this overwhelmingly positive reception, Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony, which at the time he thought of as the first of several future symphonies, should have been heard “again and yet again.” But it was not. Despite Stokowski’s advocacy for Dawson and the Negro Folk Symphony, and despite the stellar reviews it received at its premiere, within a few years both the music and its composer had faded into relative obscurity. Dawson never composed another symphony, although he did continue writing and arranging music – primarily spirituals, which he preferred to call “Negro folk songs” – for the rest of his long career.

In the current climate of racial reckoning, Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony is enjoying a long-overdue revival, as is the music of other Black classical composers such as Florence Price, William Grant Still, Nathaniel Dett, and many others.

Dawson wrote that his symphony was “symbolic of the link uniting Africa and her rich heritage with her descendants in America,” and gave each of its three movements a descriptive title. Dawson explained in his own program note: “The themes are taken from what are popularly known as Negro Spirituals. In this composition, the composer has employed three themes taken from typical melodies over which he has brooded since childhood, having learned them at his mother’s knee.” Musicologist Gwynne Kuhner Brown observes, “The themes are handled with such virtuosic flexibility of rhythm and timbre that each movement seems to evolve organically,” creating a “persuasive musical bridge between the ‘Negro Folk’ and the ‘Symphony.’”

In “The Bond of Africa,” Dawson opens with a horn solo. The dialogue between the horn and the orchestra echoes the call-and-response format of most spirituals. The horn solo repeats, usually in abbreviated form, several times throughout this movement, and serves as a musical “bond” holding the work together. The central slow movement, “Hope in the Night,” also features a unifying solo. Here an English horn sounds Dawson’s own spiritual-inspired melody, which he described as an “atmosphere of the humdrum life of a people whose bodies were baked by the sun and lashed with the whip for two hundred and fifty years; whose lives were proscribed before they were born.” Underneath the plaintive tune, the orchestra provides a dirge-like accompaniment that builds to an ominous repetition of the solo for tutti orchestra. This episode is offset by an abrupt change of mood, and we hear a lighthearted, up-tempo reworking of the original tune (the “hope” of the movement’s title). These two contrasting interludes alternate throughout the rest of the movement. Towards the end, Dawson reworks the harmony, which has been grounded in minor keys up to this point, and tiptoes towards major tonalities without fully embracing them. Musically, this device works as a powerful metaphor for the importance and elusive nature of hope to sustain people through traumatic circumstances.

The closing section, “Oh, Le’ Me Shine, Shine Like A Morning Star!” imagines a world in which the hopes of the previous movement are fully realized. Dawson creates this musical utopia through rhythm. The central melody showcases accented off-beat exclamations from various solo instruments and sections throughout, as the rhythms layer increasingly complex parts over one another. Dawson revised this movement in the early 1950s after he encountered the intricate polyrhythms of West African music during a trip to Africa. The interlocking parts and the sounds of African percussion instruments captured Dawson’s ear; when he returned to America, he added these elements. Eventually all these rhythmic strands come together in a final buoyant exclamation.

Lili Boulanger

D’un matin de printemps (From A Spring Morning)

Composer: born August 21, 1893, Paris; died March 15, 1918, Mézy-sur-Seine

Work composed: 1917-18. Boulanger made arrangements in multiple versions: for violin and piano, string trio, and full orchestra

World premiere: undocumented

Instrumentation: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, bass drum, castanets, cymbals, tambourine, tam-tam, timbales, triangle, celeste, harp, and strings

Estimated duration: 5 minutes

Women composers, like other female creative artists, have to fight battles their male counterparts do not. Even today, a female visual artist, writer, or composer is sometimes evaluated on criteria that have little or nothing to do with her work, and everything to do with her gender, her appearance, or her life circumstances. Lili Boulanger was no exception.

The younger sister of composer and pedagogue Nadia Boulanger, who taught composition to many of the 20th century’s most distinguished composers, Lili Boulanger revealed her enormous talent at a very young age. She was a musical prodigy born into a musical family; in 1913, at age 20, she became the first woman to win the coveted Prix de Rome, France’s most prestigious composition prize. Boulanger’s compositional style, while grounded in the prevailing impressionistic aesthetics associated with Claude Debussy, is nonetheless wholly her own. Her music features rich harmonic colors, hollow chords (open fifths and octaves), ostinato figures, running arpeggios, and static rhythms.

Along with her tremendous musical ability, Boulanger was born with a chronic, debilitating intestinal illness, probably Crohn’s disease. Today there are drugs and other therapies to manage this condition, but in Boulanger’s time the illness itself had neither name nor cure, and its treatment was likewise little understood. Throughout her short life, Boulanger suffered from acute abdominal pain, bouts of uncontrollable diarrhea, and constant fatigue; all these symptoms naturally impacted her stamina and her ability to write. Contemporary reviews of Boulanger’s work always emphasized her physical fragility, often in lieu of a thoughtful assessment of her music.

Despite illness, Boulanger continued composing, even on her deathbed. D’un matin printemps, the second half of a diptych that includes its shorter counterpart D’un soir triste (From a Sad Evening) are two of the last works she wrote. Both pieces treat the same opening melodic and rhythmic theme in different ways: in D’un soir triste, the tempo is slow and the mood elegiac, while the same melodic/rhythmic fragment receives a cheerful, puckish treatment in D’un matin printemps that sparkles with effervescence and youthful joy.

George gershwin

An American in Paris

Composer: born September 26, 1898, Brooklyn, NY; died July 11, 1937, Hollywood, CA

Work composed: March - June 1928, while Gershwin and his siblings were vacationing in Paris

World premiere: Walter Damrosch led the New York Philharmonic on December 13, 1928 in New York

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 3 saxophones (alto, tenor, baritone), 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, bells, cymbals, snare drum, taxi horns, tom-toms, triangle, xylophone, celesta, and strings

Estimated duration: 17 minutes

“My purpose here is to portray the impression of an American visitor in Paris, as he strolls about the city and listens to various street noises and absorbs the French atmosphere,” wrote George Gershwin about his tone poem, An American in Paris. “As in my other orchestral compositions, I’ve not endeavored to represent any definite scenes in this music. The rhapsody is programmatic only in a general impressionistic way, so that the individual listener can read into the music such as his imagination pictures for him,” This highly evocative, colorful symphonic music expertly captures the sights and sounds of Paris as its American protagonist wanders through the city streets. To illustrate the American’s journey, Gershwin included several of what he termed “walking themes,” which recur throughout the work. The trumpet sounds the most recognizable of these, the “homesick music,” in a bluesy solo. The “American” section concludes with an up-tempo Charleston played by a pair of trumpets, and the walking themes return. Finally, the orchestra winds up with a glittering exuberant finale as night falls on the City of Light.

An American in Paris marked a breakthrough for Gershwin as a composer, as the first symphonic piece for which he created his own orchestrations. When Rhapsody in Blue premiered in 1924, Gershwin was criticized because the Rhapsody’s orchestral version was created by Ferde Grofé. Four years after Rhapsody’s premiere, with An American In Paris, Gershwin demonstrated his growing command of orchestral colors, effectively silencing his detractors.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

Holiday Candlelight Concert

Tuesday, December 19, 2023 at 8 pm

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Holiday Candlelight Concert

Tuesday, December 19, 2023

Doors Open at 7 pm

Concert Starts at 8 pm

Our Lady of Fatima Church

505 W. Granger Avenue, Modesto

Program

Camille Saint-Saëns

Prelude (from Oratorio De Noel)

John Rutter

What Sweeter Music

Ludwig Van Beethoven arr. Andrew Duncan

Fanfare on Ode to Joy

- Opus Handbell Ensemble -

arr. Cathy Moklebust

The First Noel

arr. Tom Kennedy

Joy to the World

- Audience Sing-Along -

arr. Steven Pilkington

Coventry Carol

Gustav Holst

Christmas Day

Johann Sebastian Bach arr. Daniel R. Afonso Jr.

Contrapunctus (from Art of the Fugue)

Johann Sebastian Bach

Orchestral Suite No. 2 in B Minor

II. Rondeau

VII. Badinerie

arr. Tom Kennedy

O Little Town of Bethlehem

- Audience Sing-Along -

D. Kantor arr. J. Ferguson

Night of Silence

arr. Joel Raney, Arnold Sherman

An Angelic Celebration

- Opus Handbell Ensemble -

Cathy Moklebust

Vivacio

arr. Tom Kennedy

Silent Night