Program Notes: Williams & Rachmaninoff

Program Notes for October 10 & 11, 2025

Williams & Rachmaninoff

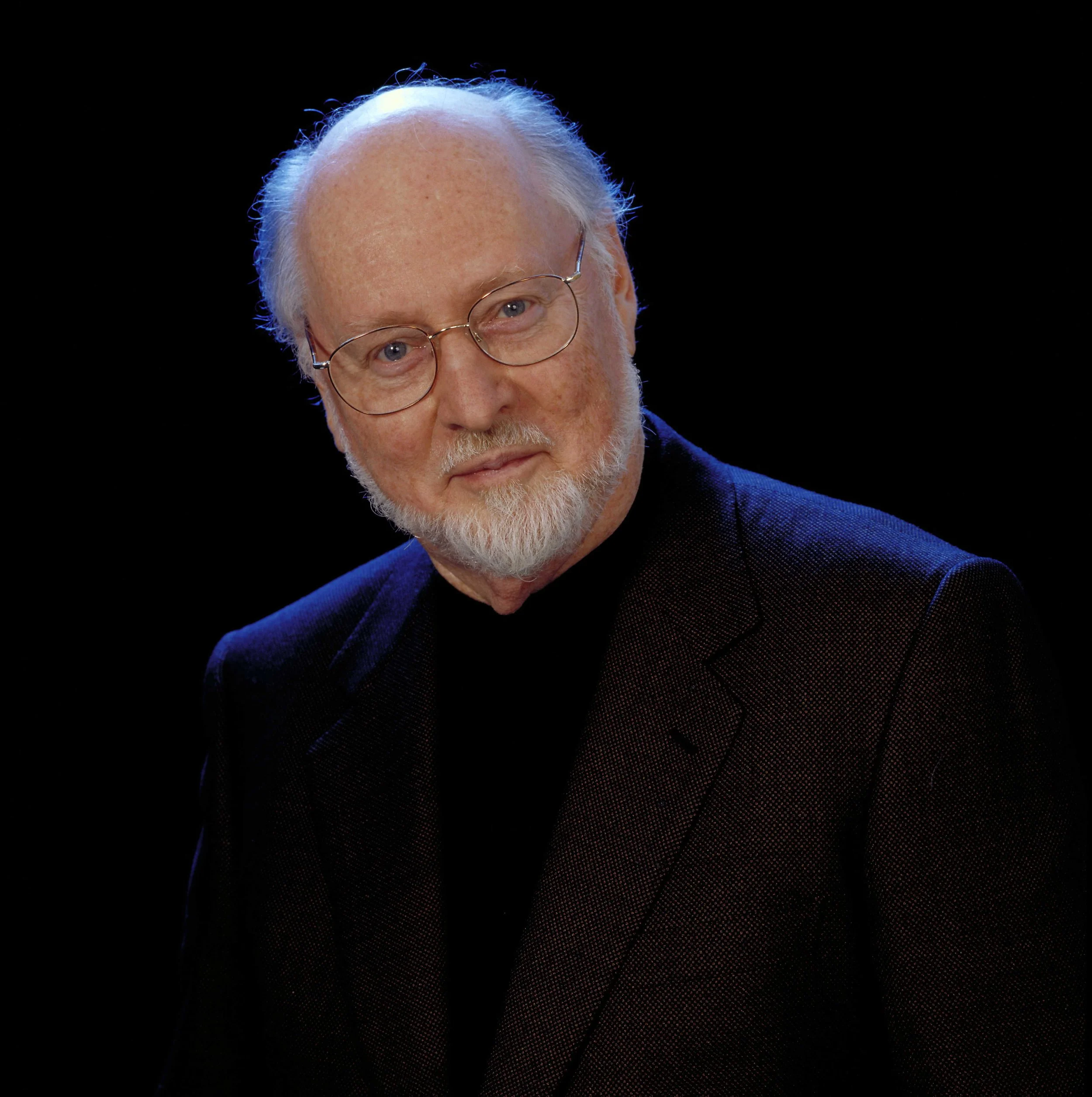

John Williams

Concerto for Cello and Orchestra

Composer: born February 8, 1932, Flushing, Queens, NY

Work composed: 1993-94. Commissioned by Seiji Ozawa and the Boston Symphony and composed for cellist Yo-Yo Ma.

World premiere: Williams led Yo-Yo Ma and the Boston Symphony on July 7, 1994, at Tanglewood, to mark the opening of Seiji Ozawa Hall.

Instrumentation: solo cello, 3 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets (1 doubling bass clarinet), 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 4 trombones, timpani, bass drum, chimes, glockenspiel, marimba, mark tree, small triangle, suspended cymbal, tam-tam, triangle, tuned drums, vibraphone, harp, piano/celesta, and strings

Estimated duration: 30 minutes

“Music is our oxygen.”

Composer John Williams is synonymous with movie music. He became a household name with the Academy Award-winning score he wrote in 1977 for Star Wars, and he has defined the symphonic Hollywood sound ever since. In addition to the Star Wars films, Williams composed the music for Jaws, the Raiders of the Lost Ark films, Superman, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T., the Jurassic Park films, Schindler’s List, the Harry Potter series, and many other films.

Williams has also composed a considerable body of concert works, including six concertos. Like his scores, Williams’ concert music also features his masterful orchestration and dramatic flourishes, and his concertos are designed to showcase the unique qualities of both the solo instrument and the soloist.

Williams and Ma have been good friends and collaborators for decades. “Given the broad technical and expressive arsenal available in Yo-Yo’s work, planning the concerto was a joy,” Williams writes. “I decided to have four fairly extensive movements that would offer as much variety and contrast as possible but that could be played continuously and without interruption.

“The Theme and Cadenza, after an opening salvo of brass, immediately casts the cello in a kind of hero’s role, making it the unquestioned center of attention. It’s a movement that attempts to put the cello on display in the time-honored sense of ‘concerto,’ and as the hero’s theme is developed, it ‘morphs’ into a cadenza in which I tried to create an opportunity for exploration of the theme that would be both ruminative and virtuosic.

“The second movement I call Blues.… In my mind, and without any conscious prodding on my part, the ghosts of Ellington and Strayhorn seemed to waft through the atmosphere. Invited or not, this was for me very welcome company. I set up clusters in piano and percussion that form a frame within which the cello unveils its misty quasi-improvisations.

“The Scherzo is about speed, deftness, and sleight of hand. The music romps along in triple time over a treacherous landscape where athletic exchanges are periodically and suddenly interrupted by a series of fermatas, as the orchestra and cello try to dominate and outdo each other. There’s a short tutti where it appears that the orchestra might prevail, but the cello outwits and outlasts it.

“In thinking about the finale of the concerto, I was always aware of the fact that Yo-Yo’s ability to ‘connect’ personally and even privately with every individual in his audience is perhaps the greatest of his abundant gifts. I therefore tried in Song, the concerto’s finale, to create long lyrical lines that would give the cello the opportunity to address the audience in the manner of a clear and direct soliloquy.

“Whatever virtues the concerto may have can never surpass, for me, the experience of knowing and working with Yo-Yo Ma. Happily, and with complete justice, the world loves and reveres this man, as do I, and working with him is always a joyous journey to be treasured.”

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Symphony No. 2 in E minor, Op. 27

Composer: born April 1, 1873, Oneg, Russia; died March 28, 1943, Beverly Hills, CA

Work composed: 1906-07. Rachmaninoff dedicated it to his composing teacher, Sergei Taneyev

World premiere: February 7, 1908, in St. Petersburg, with Rachmaninoff conducting

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 3 oboes (1 doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, glockenspiel, snare drum, and strings

Estimated duration: 43 minutes

Artists of all types have a love-hate relationship with critics: they need the exposure criticism brings to their work, but often scorn the critiques themselves. Other artists take criticism too much to heart and let it affect them to a debilitating degree, which was the case with Sergei Rachmaninoff. After the premiere of Rachmaninoff’s first symphony, he was so savaged by critics that he did not dare compose a note for three years. Eventually Rachmaninoff consulted a doctor, Nicolai Dahl, who used hypnotism to bolster Rachmaninoff’s flagging confidence. Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto was dedicated to Dahl, and it vindicated Rachmaninoff as a composer by becoming one of his most popular works.

After the success of the Second Piano Concerto, Rachmaninoff felt ready to tackle another symphony, and in 1906 he began work on his second. The writing was difficult for him, as he reported in a letter to a friend, and the work proceeded slowly. The final version lasted over an hour, although Rachmaninoff later suggested a number of performance cuts that shorten it by as much as 20 minutes; these cuts have become standard when programming this symphony today. Although Rachmaninoff, out of necessity, agreed to the cuts, which amounted to some 300 measures of music, he later confided to conductor Eugene Ormandy, “You don’t know what cuts do to me. It is like cutting a piece out of my heart.” Rachmaninoff might have appreciated the words of one critic, who wrote at the symphony’s premiere, “After listening with unflagging attention to its four movements, one notes with surprise that the hands of the watch have moved sixty-five minutes forward. This may be slightly overlong for the general audience, but how fresh, how beautiful it is!”

The symphony opens with a darkly murmuring theme played by the lower strings, a theme that forms the basis for the remainder of the first movement, as well as much of the rest of the symphony. The violins contrast with a lyrical melody, followed by a plaintive solo for English horn. Throughout this movement, Rachmaninoff uses solo instruments as structural signposts, indicating changes of mood or harmonic foundations.

The horns launch the Scherzo with a bold, energetic theme, and the strings continue with a bouncier, skipping melody. These are contrasted by a series of interludes, one unabashedly romantic, and others feverishly intense. As was his wont in many of his orchestral works, including the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Rachmaninoff includes the Dies irae melody (Day of Wrath) from the Requiem Mass; it appears here in the coda to the trio.

In the Adagio, Rachmaninoff’s signature romanticism is heard in the violins’ opening melody, which could easily serve as the love song in a cinematic romance. In fact, 1970s pop singer Eric Carmen wrote a hit song based on this theme, “Never Gonna Fall in Love Again.”

For the Finale, Rachmaninoff unleashes a whirlwind of vibrant joy. Buoyant strings recall the Scherzo, but this music is abruptly interrupted by the stark call of muted horns. We then hear snatches of music from previous movements, especially the Scherzo and the Adagio. The strings, playing in the style of the Italian tarantella, are the foundation for this movement, and its energy drives the symphony forward to a triumphant conclusion.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com