Program Notes: Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto

Program Notes for April 12 & 13, 2024

Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto

Astor piazzolla

Tangazo (Variations on Buenos Aires)

Composer: born March 11, 1921, Mar del Plata, Argentina; died July 5, 1992, Buenos Aires

Work composed: 1969

World premiere: 1970 in Washington, D.C., by the Ensemble Musical de Buenos Aires

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, cymbals, glockenspiel, guiro, tom-toms, triangle, xylophone, piano, and strings

Estimated duration: 15 minutes

“For me, tango was always for the ear rather than the feet.” – Astor Piazzolla

Astor Piazzolla is inextricably linked with tango. He took a dance from the back rooms of Argentinean brothels and blurred the lines between popular and “art” music to such an extent that, in the case of his music, such categories no longer apply.

Tangazo is a later composition, originally scored for solo bandoneon, piano, and strings. Piazzolla was a master of the bandoneón, a small button accordion of German origin, which originally served as a portable church organ. The distinctive sound of the bandoneón became a fundamental element of Piazzolla’s tangos; its insouciance and melancholy permeate Piazzolla’s music, even in works scored for other instruments.

Tangazo begins in the low strings, which murmur a slow introduction with more than a hint of menace. Harmonically, Tangazo often ranges beyond conventional tango tonalities to explore a modernist palette replete with unexpected detours. After the deliberate legato pace of the introduction, a solo oboe takes off with a skittish tango full of bounce and swagger. Legato interludes featuring pensive horn solos alternate with the agitated tango. Overall, Tangazo conveys restlessness, even as its last notes fade away.

Louise farrenc

Symphony No. 3 in G minor

Composer: born May 31, 1804, Paris; died September 15, 1875, Paris

Work composed: 1847

World premiere: 1849, by the Orchestre de la Société des concerts du Conservatoire in Paris

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 33 minutes

During her lifetime, Louise Farrenc was well known as both a composer and outstanding pianist. Throughout the 19th century, she was also the first and only female professor of music on the faculty of the Paris Conservatory.

Farrenc grew up in a family of artists who encouraged their daughter’s musical interests. Young Louise displayed extraordinary talent at the piano in early childhood, and soon began composing her own music. When she was 15, her parents enrolled her at the Paris Conservatory to continue her composition studies, although she was tutored privately by its faculty because women were not admitted to the Conservatory’s composition program at the time..

At 18, Louise married a flutist, Aristede Farrenc, who later founded a music publishing house. By the 1830s, Farrenc was balancing a busy, multifaceted career as a teacher, composer, and pianist who concertized all over France. As a composer, Farrenc also began expanding her portfolio from solo piano music to larger forms such as symphonies, concert overtures, and a number chamber works, including piano quintets and trios. Farrenc, unlike many female composers whose music was discovered only long after their deaths, was able to hear the public performance of all three of her symphonies – which were well-reviewed – during her lifetime.

The symphonic format evolved from earlier German and Italian genres; by the mid-19th century, symphonies epitomized German style. In fervently nationalist France, particularly in Paris, symphonies and their composers faced aesthetic discrimination from those who deemed the symphony an exclusively German art form. Moreover, the idea of a woman writing symphonic music – in the eyes of some putting herself on par with symphonic greats such as Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Schubert, and others – seemed an outrageous provocation.

After a brief Adagio for winds, a graceful Allegro ensues, featuring themes in the strings. This opening movement is full of vigor, artful melodies, and a sense of orchestral mastery. Farrenc follows this confident beginning with a serene Adagio cantabile, featuring a solo clarinet soaring over low winds and brasses, suggesting the intimacy of a woodwind quintet. An agitated Scherzo follows, full of quicksilver flashes of light and shadow that showcases the upper winds. The Finale bristles with dramatic energy and features several powerful statements that unleash the strings’ fiery virtuosity with a series of scalar passages. Minor-key symphonies of this period usually conclude in their corresponding major key, but Farrenc maintains the G-minor intensity right up to the closing notes.

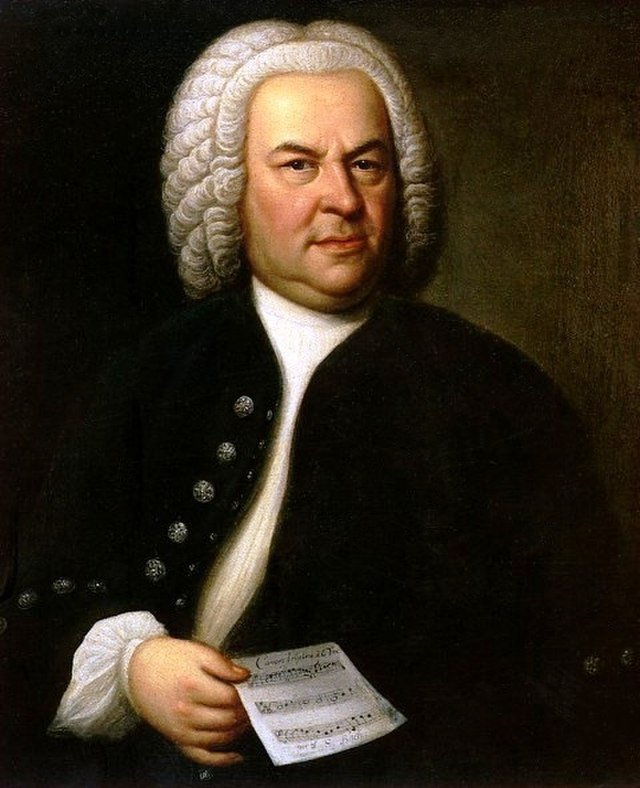

Johann Sebastian Bach

Fugue in G minor BWV 578 “Little Fugue” arr. Hersh

Composer: born March 21, 1685, Eisenach; died July 28, 1750, Leipzig

Work composed: c. 1703-07, written while Bach served as an organist in Arnstadt.

World premiere: undocumented

Instrumentation: flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, 2 horns, trumpet, chimes, vibraphone, and strings

Estimated duration: 3.5 minutes

Nicknames can be misleading. The only thing “little” about Johann Sebastian Bach’s Fugue in G minor, BWV 578, is its length. Just under four minutes long, this fugue features one of Bach’s best known and most recognizable fugue subjects, and it has been arranged for diverse ensembles, including Leopold Stowkowsi’s brass-heavy arrangement for full orchestra, and the Swingle Singers’ popular vocal jazz version.

Bach was renowned during his lifetime for his extraordinary ability to improvise at the keyboard. It is possible the distinctive fugue subject emerged first as an improvisation; at over four measures long, it is an unusually lengthy statement. Bach allows each voice to shine, including the basses (played by foot pedals on the organ). The opening three notes cut through the dense counterpoint, announcing the subject’s entrance clearly each time, as the music swirls and eddies towards a bold conclusion.

Felix Mendelssohn

Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64

Composer: born February 3, 1809, Hamburg; died November 4, 1847, Leipzig

Work composed: July 1838 – September 1844

World premiere: Niels Gade led the Gewandhaus Orchestra and violinist Ferdinand David in Leipzig on March 13, 1845

Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 27 minutes

“I would like to write a violin concerto for you next winter,” wrote Felix Mendelssohn to his longtime friend and colleague Ferdinand David in the summer of 1838. “There’s one in E minor in my head, and its opening won’t leave me in peace.” Mendelssohn, then conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, had known David for years. The two prodigies met as teenagers; 15-year-old David was a budding violin virtuoso and 16-year-old Mendelssohn had just completed his Octet for Strings. Years later, when Mendelssohn was appointed director of the Gewandhaus concerts in 1835, he hired David as concertmaster. In 1843, Mendelssohn founded the Leipzig Conservatory and quickly appointed David to the violin faculty.

Mendelssohn had played the violin since childhood, and by all accounts was quite accomplished. However, the E minor Violin Concerto required a level of technical knowledge and skill beyond Mendelssohn’s abilities, so he turned to David for hands-on advice. During the composition of the E minor Concerto, Mendelssohn wrote the melodies and designed the overall structure, while David served as technical consultant.

In this concerto, the violin is always and indisputably the star, while the orchestra’s role provides what the late music critic Michael Steinberg called “accompaniment, punctuation, scaffolding and a bit of cheerleading.” Music this familiar can be difficult to hear as a “composed” work at all; instead, it seems to emerge sui generis, like Athena bursting fully formed from the head of Zeus.

In a break with convention, the solo violin rather than the full orchestra opens the Allegro molto appassionato with the main theme. Mendelssohn also defied expectations by placing the first movement cadenza, which David composed, between the development and return of the main theme, rather than at the end of the movement.

A solo bassoon holds the last note of the Allegro and pivots without interruption to the Andante. Here the soloist leads with a lyrical, singing melody full of tender poignancy. The gentle Andante flows almost without pause into the Allegro molto vivace. The exuberant quicksilver theme of the finale contrasts sharply with the intimate Andante, and demands all the soloist’s technical and artistic skill.

Op. 64 turned out to be Mendelssohn’s last completed orchestral work; he died two years after its premiere. Scholar Thomas Grey observed, “It seems fitting, if fortuitous, that [the Violin Concerto] should combine one of his most serious and personal orchestral movements (the opening Allegro) with a nostalgic return to the world of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the finale – the world of Mendelssohn’s ‘enchanted youth’ and the music that, more than any other, epitomizes his contribution to the history of music.”

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com