Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark in Concert

May 30 & 31, 2025

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark in Concert

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

MSYO Season Finale Concert

May 10, 2025 at 2 pm

Modesto Symphony Youth Orchestra

Season Finale Concert

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Verdi's Requiem

May 9 & 10, 2025 at 7:30 pm

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Verdi’s Requiem

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Program Notes: Verdi's Requiem

Notes about:

Guiseppe Verdi: Requiem Mass (In Memory of Alessandro Manzoni)

Program Notes for May 9 & 10, 2025

Verdi’s Requiem

Giuseppe Verdi

Requiem

Composer: born October 9, 1813, Le Roncole, near Busseto, Italy; died January 27, 1901, Milano

Work composed: Verdi wrote the “Libera me” in 1868, in tribute to Gioachino Rossini. In the summer of 1873, Verdi resumed work on the Requiem, which he completed on April 10, 1874, and dedicated to the memory of Italian poet and patriot Alessandro Manzoni. Verdi’s original title, inscribed in the mss, reads “Requiem Mass for the anniversary of the death of Manzoni, 22 May 1874”

World premiere: Verdi conducted the first performance on May 22, 1874, in the church of St. Marco, Milano, with Teresa Stolz, Maria Waldmann, Giuseppe Capponi, and Ormondo Maini, vocal soloists.

Instrumentation: SATB soloists, four-part chorus, 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 4 bassoons, 4 horns, 4 trumpets (one offstage), 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, and strings.

Estimated duration: 83 minutes

“It was an impulse, or, to put it better, a need from my heart, to honour, as best I could, this great man whom I held in such esteem as a writer, and venerated as a man, and as a model of virtue and patriotism.” – Giuseppe Verdi’s letter to the Mayor of Milan, about the composer’s proposal to write a requiem mass to honor the memory of Italian writer, poet, and patriot Alessandro Manzoni.

“A great name has disappeared from the world! His was the most widespread, the most popular reputation of our time, and it was a glory of Italy! When the other one who still lives [Manzoni] is no more, what will we have left?” These were the words of Giuseppe Verdi upon hearing the news of Gioachino Rossini’s death, in 1868. It was Rossini’s passing that first inspired Verdi to think of composing a Requiem. Just days after Rossini died, Verdi wrote the Italian music publisher Ricordi, proposing a collaborative Requiem written by “the most distinguished Italian composers,” to honor Rossini’s memory. Verdi added many stipulations and conditions to his idea, including the suggestion that everyone involved with the Requiem should help finance it. For a number of reasons – financial, logistical, and political – the proposed Rossini memorial ceremony was shelved, although every composer who was asked to write a movement completed their assigned section on time (The Messa per Rossini did eventually receive a public performance – in 1988).

With the Rossini project scrapped, Verdi turned his creative attention elsewhere. In the years between 1869 and 1873, Verdi busied himself with his opera Aida, a commission from the Egyptian government to commemorate a new Egyptian opera house built to celebrate the 1869 opening of the Suez Canal. As Verdi conducted Aida around Europe, he also composed his E minor String Quartet, his only surviving piece of chamber music.

In the spring of 1873, Ricordi sent Verdi the score to his “Libera me.” A month later, Alessandro Manzoni, one of the most important writers, thinkers, and patriots of 19th-century Italy, died at the age of 88. Verdi, along with most Italians, venerated Manzoni almost to the point of sainthood (Verdi said of Manzoni’s 1827 masterpiece, I promessi sposi (The Betrothed), that it was “not only the greatest book of our epoch, but one of the greatest ever to emerge from a human brain.”) Both men were also deeply committed to the Risorgimento, the decades-long Italian political and social effort to unify all the Italian city-states into one Kingdom of Italy, with Rome as its capital. Verdi was not much given to hero worship generally, but the depth of his feelings for both Manzoni and Manzoni’s impact on Italian culture cannot be exaggerated.

With Manzoni’s death, Verdi returned immediately to the idea of a Requiem Mass to honor a true Italian hero. On June 3, 1873, Verdi wrote to Ricordi, “I too would like to demonstrate what affection and veneration I bore and bear to that Great Man who is no more, and whom Milan has so worthily honored. I would like to set to music a Mass for the Dead to be performed next year on the anniversary of his death. The Mass would have rather vast dimensions, and besides a large orchestra and a large chorus, it would also require … four or five principal singers … I would have the copying of the music done at my expense, and I myself would conduct the performance both at the rehearsals and in church.” Verdi further asked Ricordi to invite the Mayor of Milan to sanction this undertaking. Permission was soon granted, and Verdi quickly set to work.

Verdi’s Requiem, like Johannes Brahms’ Ein Deutsches Requiem, is a personal statement of grief that employs structure and text borrowed from church liturgy. However, neither Verdi nor Brahms was personally devout. For both men, the texts they chose for their respective Requiems served as an expressive outlet for the universal need to convey the emotions that surface when a beloved person dies: grief, loss, sadness, anger, fear of judgment, and the hope of a lasting peace for both the departed and the bereaved. The dramatic, operatic quality of Verdi’s requiem ill-suited it for use as part of a regular church service, and Verdi never intended it to function as liturgy. From the beginning, Verdi conceived his Requiem for performance, not worship.

Conductor Hans von Bülow’s famous remark that the Requiem was “an opera in ecclesiastical costume” was meant as condemnation. However, one can take von Bülow’s words at face value, without the harsh judgment he intended. Certainly no other Requiem comes close to approaching the drama and tension of Verdi’s, and the ebb and flow of emotion it generates parallels the narrative arc of a grand opera. The obvious passion of Verdi’s music, and the operatic vocabulary he employs throughout, need not diminish the Requiem’s impact as a profound articulation of grief. For Verdi, as for his countrymen, the only way to properly mourn Manzoni and pay homage to his unique stature in Italy was through an equally significant, expansive musical statement.

The liturgy of the requiem mass is not standardized; each composer must make specific choices regarding which texts to include. Verdi begins with the standard opening lines, “Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine” (Grant them eternal rest, O Lord), which the chorus and orchestra intone in hushed, muted phases. The four soloists join the chorus and orchestra for an exuberant “Kyrie eleison” (Lord have mercy), which makes the “Dies irae” that follows all the more terrifying. This music is the most recognizable to audiences, but familiarity cannot dent its powerful impact. The sopranos and tenors sustain a high G while the lower voices, punctuated by a shrill piccolo and a pounding bass drum, warn of the Day of Wrath, when fire shall destroy the earth, according to dire prophecy. A chorus of brasses precedes the bass soloist, who describes the sound of the trumpet that will summon all to judgment. The mezzo-soprano and chorus tell of the Book of Judgment, in which all deeds are recorded, and from which the world cannot escape. The focus shifts from prophecy to first person entreaty, as the soprano, mezzo, and tenor plead in vain for clemency (Who will intercede for me when even the just are unsafe?) The Sequence, which begins with “Dies irae” and ends with “Lacrimosa” (Weeping), covers the full emotional spectrum from abject terror to gentle entreaties for mercy, as the supplicant, on bended knee, acknowledges his/her own unworthiness.

The tender opening of the Offertorio, which features the four soloists, emphasizes the mercy of Christ. Its rocking meter suggests a lullaby, and as the singers describe the “holy light” God promised to Abraham and his descendants, both the vocal and orchestral writing grow more luminous. Verdi expertly delivers us from the pits of hell (low timbres and registers) into the glowing warmth of salvation, and readies us for the untrammeled joy of the Sanctus, with its trumpet fanfare proclaiming “Holy, holy, holy, Lord of Hosts! Heaven and earth are filled with your glory!” In the Agnus Dei, Verdi shifts from extroversion to unadorned unisonal contemplation with minimal orchestral accompaniment, as first the chorus, then the soprano and mezzo sing, “Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, grant them eternal rest.” Verdi ends his Requiem with an agitated soprano intoning the opening lines of “Libera me” (Deliver me, O Lord, from eternal death on that awful day). All the drama of the earlier sections returns, as if Verdi intended to leave us with a sense of uncertainty: will we, in the final analysis, be redeemed? Verdi reprises the music of the “Dies irae,” but eventually, the chorus and soprano end with an almost inaudible whisper, “Libera me. Libera me.”

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

Carnival of the Animals

March 14, 2025 at 7:30 pm

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Carnival of the Animals

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Program Notes: Carnival of the Animals

Notes about:

Gershwin (arr. Hersh): Three Preludes

Saint-Saëns: Carnival of the Animals

Norman: Drip Blip Sparkle Spin Glint Glide Glow Float Flop Chop Pop Shatter Splash

Copland: Four Dance Episodes from Rodeo

Program Notes for April 11 & 12, 2025

Carnival of the Animals

George gershwin

Three Preludes (arr. Hersh)

Composer: born September 26, 1898, Brooklyn, NY; died July 11, 1937, Hollywood, CA

Work composed: 1926, originally for solo piano. Dedicated to Gershwin’s friend and colleague Bill Daly

World premiere: Gershwin performed the three preludes at the Roosevelt Hotel in New York City on December 4, 1926.

Instrumentation: flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, 4 horns, trumpet, trombone, timpano, bass drum chime, glockenspiel, snare drum, suspended cymbal, tam-tam, triangle, vibraphone, woodblock, xylophone, and strings

Estimated duration: 6 minutes

After the success of Rhapsody in Blue made George Gershwin a household name, the young composer set himself the daunting task of writing 24 preludes for solo piano. He began early in 1925, but quickly abandoned the project, probably for lack of time. Between January 1925 and the premiere of Gershwin’s three preludes in December 1926, the composer wrote no less than four Broadway shows, made two trips to Europe, and composed and performed his Concerto in F with the New York Philharmonic.

These three concise, highly atmospheric pieces have become favorites with both musicians and audiences since their premiere. Arrangements for small orchestra, solo instruments and piano, particularly for violin, clarinet, and other winds, have proved as popular as Gershwin’s original versions. The first prelude centers on a distinctive blue note theme set to a syncopated jazz rhythm. Gershwin described the second prelude as “a sort of blues lullaby;” its languid melody suggests both fatigue and melancholy. The third piece, which Gershwin referred to as “the Spanish prelude,” combines a striking offbeat rhythmic motif with jazz-flavored melodies.

Camille Saint-saËns

Canival of the Animals

Composer: born October 9, 1835, Paris; died December 16, 1921, Algiers

Work composed: February 1886

World premiere: March 3, 1886, in a private concert hosted by cellist Charles Lebouc in Paris.

Instrumentation: 2 solo pianos, flute (doubling piccolo), clarinet, glass harmonica (or glockenspiel), xylophone, and strings

Estimated duration: 22 minutes

Camille Saint-Saëns occupies a pivotal place in the history of French music. His numerous compositions include works in every genre, and, stylistically, his music bridges the gap between Berlioz and Debussy. (Before Saint-Saëns, 19th-century French music was virtually synonymous with opera; Berlioz’ Symphonie fantastique is a notable, but isolated, exception.)

Through his many instrumental works, Saint-Saëns expanded the boundaries of French music to include a broad array of orchestral and chamber works, thus raising the profile of French music internationally.

Saint-Saëns wanted his music to outlive him, and to be remembered as a significant composer. Ironically, he is best known today for his Carnival of the Animals, a satirical “witty fantasy burlesque,” in the words of a colleague, and one he refused to have published during his lifetime, fearing it would tarnish his reputation as a writer of “serious” music. (Interestingly, Saint-Saëns also stipulated in his will that Carnival be published after his death; Durand brought out the first edition in 1922). Originally written for two pianos and chamber ensemble, Carnival of the Animals has delighted children and adults for more than a century. Excerpts from Carnival have also entered popular culture through classic cartoons, films, and television commercials.

In 1885, Saint-Saëns embarked on an extensive concert tour of Germany, but his well-publicized negative opinions on the music of Richard Wagner enraged German audiences, and many of Saint-Saëns scheduled concerts were abruptly cancelled. In January 1886, Saint-Saëns took himself off to an out-of-the-way Austrian village to rest and recover. While there, Saint-Saëns amused himself by writing a humorous, satirical suite, each movement depicting a different animal.

Musical jokes and well-known quotations from other works appear throughout Carnival, which opens with a glittering tremolo of an Introduction that gives way to the magisterial Royal March of the Lion, music befitting the all-powerful King of the Jungle. Saint-Saëns effectively captures the hither-and-thither bustle of Hens and Roosters darting about, pecking at seeds on the ground while the clarinet squawks the rooster’s crow. Both pianists execute a headlong gallop up and down the keyboard as Wild Donkeys race past. Saint-Saëns pokes fun at the Tortoises’ sluggish pace with a slowed-down-to-a-crawl version of the famous high-stepping theme of the French Can-Can. The Elephant waltzes to a gently lumbering tune in the double basses, accompanied by delicate flourishes from the pianos. The pianos jumping chords depict Kangaroos hopping here and there, pausing now and then to look around. In The Aquarium, lissome fishes swim through sun-dappled water, while the strings’ flowing melody hints at mysterious underwater realms, accented by sharp pings of the glockenspiel and the pianos’ sinuous accompaniment.

The bray of Donkeys is featured in the brief Characters With Long Ears. Next, the pianos establish a quiet forest scene for The Cuckoo, whose characteristic call is sounded by the clarinet. Flocks of colorful tuneful birds surround us in The Aviary, as the flute’s nimble fluttering evokes their breathless flights. In the original score, Saint-Saëns tells the Pianists to “imitate the hesitant style and awkwardness of a beginner,” as they play a series of tedious scales and other practice exercises. In Fossils, the only non-living animals in the Carnival, Saint-Saëns borrows from his own Danse macabre to portray Fossils dancing to the metallic staccato sound of the xylophone. Quotes from other well-known tunes including “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” the French children’s song “Au clair de la lune,” and a quick nod to an aria from Rossini’s Barber of Seville are also featured.

The Swan is the only movement from Carnival that Saint-Saëns allowed to be published during his lifetime, in an arrangement for piano and cello. The piano’s graceful, understated arpeggios support the cello’s fluid unbroken melody as the swan glides with seeming effortlessness over the waters of a still pond.

In the joyful Finale, Saint-Saëns reprises snippets from previous movements, as the animals celebrate. True to form, the Donkeys have the last word, hee-hawing the Carnival to a close.

When Carnival was published and publicly performed after Saint-Saëns death, it was hailed by all as an unqualified delight. The newspaper Le Figaro’s review was typical: “We cannot describe the cries of admiring joy let loose by an enthusiastic public. In the immense oeuvre of Camille Saint-Saëns, The Carnival of the Animals is certainly one of his magnificent masterpieces. From the first note to the last it is an uninterrupted outpouring of a spirit of the highest and noblest comedy. In every bar, at every point, there are unexpected and irresistible finds. Themes, whimsical ideas, instrumentation compete with buffoonery, grace and science …”

Andrew Norman

Drip, Blip, Sparkle, Spin, Glint, Glide, Glow, Float, Flop, Chop, Pop, Shatter, Splash

Composer: born October 31, 1979, Grand Rapids, MI

Work composed: Commissioned by the Minnesota Orchestra for their Young People’s Concert Series in 2005.

World premiere: Bill Schrickel led the Minnesota Orchestra in the premiere on November 2, 2005, in Orchestra Hall, Minneapolis, MN.

Instrumentation: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 3 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, brake drum, crotales, ratchet, snare drum, slapstick, tambourine, tam-tam, triangle, vibraphone, woodblock, xylophone, piano and strings

Estimated duration: 4 minutes

Andrew Norman is a composer, educator, and advocate for the music of others. Praised as “the leading American composer of his generation” by the Los Angeles Times, and “one of the most gifted and respected composers of his generation” by the New York Times, Norman has established himself as a significant voice in American classical music.

Norman’s music often takes inspiration from architectural structures and visual cues. His music draws on an eclectic mix of instrumental sounds and notational practices, and it has been cited in the New York Times for its “daring juxtapositions and dazzling colors,” and in the Los Angeles Times for its “Chaplinesque” wit.

Drip, Blip, Sparkle, Spin, Glint, Glide, Glow, Float, Flop, Chop, Pop, Shatter, Splash was conceived as a “get-to-know-you” piece to introduce young listeners to the multifaceted sounds of the orchestra. “The process of writing it was a bit like making a tossed salad,” says Norman. “I chopped up sounds from the orchestra – one sound for each of the thirteen verbs in the title – and then I tossed them all together and called it a piece.”

The four-minute work whizzes by with the hyperkinetic energy of a Tom & Jerry cartoon. Each word of the title is delightfully and recognizably embodied by myriad, disparate sounds, from a battery of percussion instruments to muted brasses to bows playing col legno (on the wood) and a single woodblock ticking with anticipatory hold-your-breath excitement. Audience members should note that the verbs of the title are not necessarily depicted in order, but are encouraged to identify each one nonetheless.

aaron copland

Four Dance Episodes from Rodeo

Composer: born November 14, 1900, Brooklyn, NY; died December 2, 1990, North Tarrytown, NY

Work composed: The ballet Rodeo, from which this suite of dances is adapted, was commissioned in 1942, by the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, with choreography by Agnes de Mille. Shortly after its premiere in October 1942, Copland arranged the Four Dance Episodes for orchestra.

World premiere: Alexander Smallens led the New York Philharmonic at the Stadium Concerts in July 1943

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (2 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, orchestra bells, slapstick, snare drum, triangle, wood block, xylophone, harp, piano, celesta, and strings.

Estimated duration: 18 minutes

When choreographer Agnes de Mille approached Aaron Copland about collaborating on a new “cowboy ballet,” Copland was less than enthusiastic. Copland’s 1938 ballet about the outlaw Billy the Kid had already given the composer the opportunity to explore Western musical themes in his work, and he saw de Mille’s project as more of the same. But de Mille, then a young and largely unknown choreographer, convinced the skeptical Copland her ballet was sufficiently different from Billy the Kid – a basic, universally appealing story set against the epic sweep of the American West – and Copland eventually agreed.

De Mille’s scenario featured a tomboyish Cowgirl from Burnt Ranch who shows up the ranch hands by out-lassoing them while roping bucking broncos. She is drawn to the Head Wrangler, who takes little notice of her, despite her obvious skills as a cowboy, until she puts on a pretty dress and makes eyes at him at the Saturday night barn dance.

As he did in Billy the Kid, Copland makes use of several authentic cowboy songs. After a high-energy brass introduction, Buckaroo Holiday features the song “If He Be a Buckaroo by His Trade,” (trombone solo approximately halfway through the movement). In the gentle Corral Nocturne, Copland quotes the song “Sis Joe” (about a train named Sis Joe heading for California’s Gold Rush country). By slowing down the song’s usual tempo, Copland creates an intimate, wistful interlude that captures the Cowgirl’s loneliness. The relaxed, low-key Saturday Night Waltz features a famous cowboy song, “I Ride An Old Paint. Hoe Down is the most recognized movement from Rodeo, thanks to its use in a popular commercial advertising American beef. In the final scene of the ballet, at a boisterous hoe-down, the cowgirl appears in a party dress, and the cowboys finally notice her. After a rhythmic introduction, “Bonaparte’s Retreat,” “McLeod’s Reel,” and other square dances fill the air with foot-stomping, thigh-slapping tunes.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

Aretha: A Tribute

March 14, 2025 at 7:30 pm

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Aretha: A Tribute

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

MSYO Spring Concert

February 8, 2025 at 2 pm

Modesto Symphony Youth Orchestra

Spring Concert

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Disney's Fantasia in Concert Live to Film

Feb. 7 & 8, 2025 at 7:30 pm

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Disney’s Fantasia in Concert Live to Film

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Holiday Candlelight Concert

Tuesday, December 19, 2023 at 8 pm

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Holiday Candlelight Concert

Tuesday, December 17, 2024

Doors Open at 7 pm

Concert Starts at 8 pm

St. Stanislaus Catholic Church

1200 Maze Boulevard, Modesto

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “CANDLELIGHT” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Holiday Pops!

December 6, 2024 at 7:30 pm

December 7, 2024 at 2 pm

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Holiday Pops!

Friday, December 6, 2024 at 7:30 pm

Saturday, December 7, 2024 at 2 pm

Mary Stuart Rogers Theater, Gallo Center for the Arts

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this weekend’s performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

The Four Seasons Mixtape

November 1 & 2, 2024 at 7:30 pm

VISIT MOBILE PROGRAM →

READ OUR PROGRAM NOTES →

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE VERSION →

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

The Four Seasons Mixtape

November 1 & 2, 2024 at 7:30 pm

Gallo Center for the Arts, Mary Stuart Rogers Theater

Nicholas Hersh, conductor

Audrey Wright, violin

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Program Notes: The Four Seasons Mixtape

Notes about:

Mendelssohn’s Overture from A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Ortiz’s La Calaca for String Orchestra

The Four Seasons Mixtape:

Vivaldi’s L’estate (Summer)

Richter’s Autumn from The Four Seasons Recomposed

Ysaÿe’s Chant d’hiver (Wintersong)

Piazzolla’s Primavera portena (Beunos Aires Spring)

Program Notes for November 1 & 2, 2024

The Four Seasons Mixtape

Felix Mendelssohn

Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Op. 21

Composer: born February 3, 1809, Hamburg; died November 4, 1847, Leipzig

Work composed: 1826

World premiere: Mendelssohn’s first version of the Overture was a two-piano arrangement for himself and his sister Fanny, which they premiered at their home in Berlin on November 19, 1826, for their piano teacher, Ignaz Moscheles. After that performance, Mendelssohn scored the work for orchestra and conducted the first performance of the orchestral version himself the following February in the city of Stettin.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, tuba, timpani, and strings.

Estimated duration: 11 minutes

In July 1826, Felix Mendelssohn began composing what would become one of his most enduring works. Immediately upon its completion, the Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream established the 17-year-old Mendelssohn as a composer of depth and astonishing maturity.

Young Felix and his family were ardent fans of Shakespeare, whose works had been translated into German in 1790. Mendelssohn’s grandfather Moses had read the plays in English and had attempted some translations of his own, including bits from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Felix and his older sister, the equally talented Fanny, immediately took to the fanciful play and staged a series of at-home performances, each child playing multiple roles. In a letter to their sister Rebecka some years after the Overture was composed, Fanny wrote, “Yesterday we were thinking about how the Midsummer Night’s Dream has always been such an inseparable part of our household, how we read all the different roles at various ages, from Peaseblossom to Hermia and Helena … We have really grown up together with the Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Felix, in particular, has made it his own.”

Much more than a simple introduction, Mendelssohn’s Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream serves as the perfect musical description of Shakespeare’s play, which was Mendelssohn’s intention. He thought of the work as a kind of mini-tone poem, rather than a musical prologue to the play itself. In just twelve minutes, Mendelssohn captures the airy magic that imbues the story: the opening chords representing the enchanted forest; the lissome, iridescent violin passages evoking fairies fluttering here and there; the alternately affectionate and turbulent encounters among the four lovers; the dismaying bray of Bottom after he is transformed into a donkey. It is a stunning achievement for a composer of any age.

While he was at work on the Overture, Mendelssohn played violin in an orchestra that performed the overture to Carl Maria von Weber’s opera Oberon. In a letter to his father and sister, Mendelssohn sketched out several of its themes, all musical representations of ideas from the opera’s libretto. This experience suggested to Mendelssohn that he intertwine recurring motifs into his own Overture that would, in his words, “weave like delicate threads throughout the whole.”

Gabriela Ortiz

La Calaca for String Orchestra (The Skull)

Composer: born December 20, 1964, Mexico City

Work composed: originally the final movement of Altar de Muertos, a string quartet written for and commissioned by the Kronos Quartet in 1996-97. Arranged for string orchestra in 2021

World premiere: John Adams led the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra at Libbey Bowl in Ojai, CA, on September 19, 2021.

Instrumentation: string orchestra

Estimated duration: 10 minutes

Born into a musical family, Gabriela Ortiz has always felt she didn’t choose music – music chose her. Her parents were founding members of the group Los Folkloristas, a renowned music ensemble dedicated to performing Latin American folk music. Growing up in cosmopolitan Mexico City, Ortiz’s music education was multifaceted; she played charango and guitar with Los Folkloristas while also studying classical piano. Later, Ortiz was mentored in composition by renowned Mexican composers Mario Lavista, Julio Estrada, Federico Ibarra, and Daniel Catán. Ortiz continued her studies in Europe, earning a doctorate in composition and electronic music from London’s City University under the guidance of Simon Emmerson.

Ortiz’s music incorporates seemingly disparate musical worlds, from traditional and popular idioms to avant-garde techniques and multimedia works. This is, perhaps, the most salient characteristic of her oeuvre: an ingenious merging of distinct sonic worlds. While Ortiz continues to draw inspiration from Mexican subjects, she is interested in composing music that speaks to international audiences.

Conductor Gustavo Dudamel, a longtime champion of Ortiz’s music, stated: “Gabriela is one of the most talented composers in the world – not only in Mexico, not only in our continent – in the world. Her ability to bring colors, to bring rhythm and harmonies that connect with you is something beautiful, something unique.” Under Dudamel’s direction, the Los Angeles Philharmonic has commissioned and premiered seven works by Ortiz in recent years, including her ballet Revolución diamantina (2023), her violin concerto Altar de Cuerda (2021), and Kauyumari (2021) for orchestra. These three works are featured on the album Revolución diamantina, which was released in June 2024.

La Calaca began as the final movement of Altar de Muertos (Altar of the Dead), a string quartet commissioned by the Kronos Quartet. Altar de Muertos reflects the traditions and festivities of the Day of the Dead. Ortiz writes, “The tradition of the Day of the Dead festivities in Mexico is the source of inspiration for the creation of a work for string quartet whose ideas could reflect the internal search between the real and the magic, a duality always present in Mexican culture, from the past to this present.”

Each movement of Altar embodies the “diverse moods, traditions and the spiritual worlds which shape the global concept of death in Mexico, plus my own personal concept of death,” Ortiz explains. In La Calaca, the music expresses “Syncretism [in religion, the practice of merging beliefs and rituals from disparate traditions] and the concept of death in modern Mexico, chaos and the richness of multiple symbols, where the duality of life is always present: sacred and profane; good and evil; night and day; joy and sorrow. This movement reflects a musical world full of joy, vitality, and a great expressive force. At the end of La Calaca I decided to quote a melody of Huichol origin, which attracted me when I first heard it. That melody was sung by Familia de la Cruz. The Huichol culture lives in the State of Nayarit, Mexico. Their musical art is always found in ceremonial and ritual life.”

The Four Seasons Mixtape

“A mixtape, harkening back to the days of holding a cassette recorder up to the radio, has come into the modern lexicon as a compilation of different musical selections, often from different artists or composers, and usually evoking some similar mood or subject matter,” writes Modesto Symphony Orchestra’s Music Director Nicholas Hersh. “In fact, Vivaldi’s Four Seasons is perhaps an early representation of this concept: a set of four violin concerti, each of which can be performed separately, but when taken together they form a greater narrative. Our MSO ‘Four Seasons Mixtape’ takes this a step further by assigning each season to a different composer. Vivaldi’s original Summer sets the tone, and Max Richter’s Autumn [Recomposed] follows it up with a ‘remix’ of the Baroque sound with modern harmony and syncopation. Belgian violin virtuoso Eugene Ysaÿe’s Wintersong imparts a Romantic sumptuousness to an otherwise bleak season, and finally Astor Piazzolla takes us home with his uproarious Buenos Aires Spring, infused with the rhythms of the Tango.

“It is no easy feat to perform such wildly different musical styles as part of the same whole, and I am so grateful to Audrey Wright for realizing this Mixtape with us!”

Antonio Vivaldi

“L’estate” (Summer) from The Four Seasons for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 8 No 2

Composer: born March 4, 1678, Venice; died July 27/28, 1741, Vienna

Work composed: published 1725. Dedicated to Count Wenceslas Morzin.

World premiere: undocumented

Instrumentation: solo violin, continuo, and strings

Estimated duration: 11.5 minutes

Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons are some of the most recognizable and most performed Baroque works ever written. They have also been used by numerous companies to sell products, from diamonds to high-end cars to computers. With that level of exposure, it is easy to assume we “know” The Four Seasons, but there is more to these concertos than meets the eye, or the ear.

The Four Seasons are part of a larger collection of concertos Vivaldi titled Il cimento dell’armonia e dell’inventione (The contest between harmony and invention). Each concerto is accompanied by a sonnet, possibly written by Vivaldi himself, which gives specific descriptions of the music as it unfolds.

Summer’s slow introduction evokes a hot, humid summer day: “Under the merciless summer sun languishes man and flock; the pine tree burns … ” Lethargic birdcalls are abruptly interrupted by violent thunderstorms. In the slow movement, the soloist (shepherd) cries out in fear for his flock in the blistering heat. While he laments, the ensemble becomes buzzing flies. The final movement morphs into a tremendous hailstorm that destroys the crops.

Max Richter

“Autumn” from The Four Seasons Recomposed

Composer: born March 22, 1966, Hamelin, Lower Saxony, West Germany

Work composed: 2011-12

World premiere: André de Ridder led the Britten Sinfonietta with violinist Daniel Hope at the Barbican Centre on October 31, 2012, in London.

Instrumentation: solo violin and strings

Estimated duration: 8 minutes

Max Richter’s fusion of classical music and electronic technology, as heard in his genre-defining solo albums and numerous scores for film, TV, dance, art, and fashion, has blazed a trail for a generation of musicians.

In 2011, the recording label Deutsche Grammophon invited Richter to join its acclaimed Recomposed series, in which contemporary artists are invited to re-work a traditional piece of music. Richter chose Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons. In a 2014 interview with the website Classic FM, Richter explained, “When I was a young child I fell in love with Vivaldi’s original, but over the years, hearing it principally in shopping centres, advertising jingles, on telephone hold systems and similar places, I stopped being able to hear it as music; it had become an irritant – much to my dismay! So I set out to try to find a new way to engage with this wonderful material, by writing through it anew – similarly to how scribes once illuminated manuscripts – and thus rediscovering it for myself. I deliberately didn’t want to give it a modernist imprint but to remain in sympathy and in keeping with Vivaldi’s own musical language.”

“ … The key thing for me to figure out when navigating through this material was just how much Vivaldi and how much me was happening at any point,” Richter continued. “Three quarters of the notes in the new score are mine, but that is not the whole story. Vivaldi’s DNA is omnipresent in the work, and trying to take that into account at all times was the key challenge for me.”

Richter’s version of “Autumn” inserts syncopations (rhythmic off-beats) and subtle electronics into Vivaldi’s original music; the overall effect blurs the boundaries between which phrases are Vivaldi’s and which are Richter’s to a remarkable degree. “I’ve used electronics in several movements, subtle, almost inaudible things to do with the bass,” says Richter, “but I wanted certain moments to connect to the whole electronic universe that is so much part of our musical language today.”

During the recording sessions for Richter’s Recomposed Four Seasons, the composer adds, “In the second movement of ‘Autumn,’ I asked the harpsichordist Raphael Alpermann to play in what is a rather old-fashioned way, very regularly, rather like a ticking clock. That was partly because I didn’t want the harpsichord part to be attention-seeking, but also because that style connects to various pop records from the 1970s where the harpsichord or Clavinet was featured, including various Beach Boys albums and the Beatles’ Abbey Road.”

Eugène Ysaÿe

Chant d’hiver (Winter Song)

Composer: born July 16, 1858, Liège, Belgium; died May 12, 1931, Liège

Work composed: 1902

World premiere: undocumented

Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 12.5 minutes

Known during his lifetime as “The King of the Violin,” Eugène Ysaÿe was also a noted composer and conductor. Born 18 years after the death of the legendary Italian violinist Niccolò Paganini, the Belgian virtuoso was – and is – widely considered the greatest violinist of his time. This opinion was shared by the foremost composers of the latter 19th – and early 20th-century, including Claude Debussy, Ernest Chausson, Gabriel Faurè, and fellow Belgian César Franck, all of whom dedicated works to Ysaÿe.

Ysaÿe’s Chant d’hiver was inspired by a famous poem from medieval French poet François Villon (c.1431-after 1463). The poem, known in English as “Ballad of the Ladies of Bygone Times,” features a wistful refrain, “But where are the snows of yesteryear?” The exquisite melancholy of the soloist’s long phrases and the orchestra’s deft accompaniment evoke an air of longing – and also captures the quintessentially Romantic situation in which one is sad while simultaneously finding an odd pleasure in it.

Astor Piazzolla

“Primavera porteña” from Cuatro estaciones porteñas de Buenos Aires (“Spring” from The Four Seasons of Buenos Aires)

Composer: born March 11, 1921, Mar del Plata, Argentina; died July 5, 1992, Buenos Aires

Work composed: Piazzolla originally composed the Cuatro estaciones porteñas de Buenos Aires for Melenita de oro, a play by his countryman, Alberto Rodríguez Muñoz. The movements were written individually, between the years 1965 -1970, and Piazzolla did not originally intend them to be performed as a single work. The original version of Cuatro estaciones is scored for Piazzolla’s quintet, which consisted of violin, electric guitar, piano, bass, and bandóneon (a large button accordion). Tonight’s arrangement, for solo violin and string orchestra, was created in 1999 by Leonid Desyatnikov for violinist Gidon Kremer.

World premiere: Piazzolla and his quintet played the Cuatro estaciones for the first time at the Teatro Regina in Buenos Aires, on May 19, 1970.

Instrumentation: solo violin and strings

Estimated duration: 5 minutes

“For me, tango was always for the ear rather than the feet.” – Astor Piazzolla

Astor Piazzolla and tango are inseparably linked. He took a dance from the back rooms of Argentinean brothels and blurred the lines between popular and “art” music to such an extent that such categories no longer apply.

In the mid-1950s, Piazzolla went to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger, one of the 20th century’s most renowned composition teachers. She was unimpressed with the scores he showed her but, after insisting he play her some of his own tangos, she declared, “Astor, this is beautiful. I like it a lot. Here is the true Piazzolla – do not ever leave him.” Piazzolla later called this “the great revelation of my musical life,” and followed Boulanger’s advice. He took tango’s raw passion and fire, with its powerful rhythms and edgy melodies, and made it an essential part of classical repertoire.

The version of the Cuatro estaciones porteñas de Buenos Aires heard on tonight’s program was created in 1999 by Russian composer/arranger Leonid Desyatnikov, at the request of violinist Gidon Kremer. Desyatnikov not only arranged Cuatro estaciones, but also inserted quotes from Antonio Vivaldi’s Four Seasons into Piazzolla’s music.

Tango’s musical style requires several string techniques not often heard in classical music: wailing glissandos, sharp pizzicatos that threaten to break strings, bouncing harmonics and, in particular, a harsh, scratchy, distinctly “un-pretty” manner of bowing, sometimes using the wood, rather than the hair, of the bow.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

Branford Marsalis with the Modesto Symphony Orchestra

October 5, 2024 at 7:00 pm

VISIT MOBILE PROGRAM →

READ OUR PROGRAM NOTES →

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE VERSION →

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Branford Marsalis with the Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Saturday, October 5, 2024 at 7:30 pm

Gallo Center for the Arts, Mary Stuart Rogers Theater

Nicholas Hersh, conductor

Branford Marsalis, alto saxophone

Program

Alexander Borodin (1833-1887)

Polovtsian Dances from Prince Igor (1890)

Darius Milhaud (1892-1974)

Scaramouche, Op. 165c (1937)

Branford Marsalis, saxophone

i.Vif

ii.Modéré

iii.Brazileira

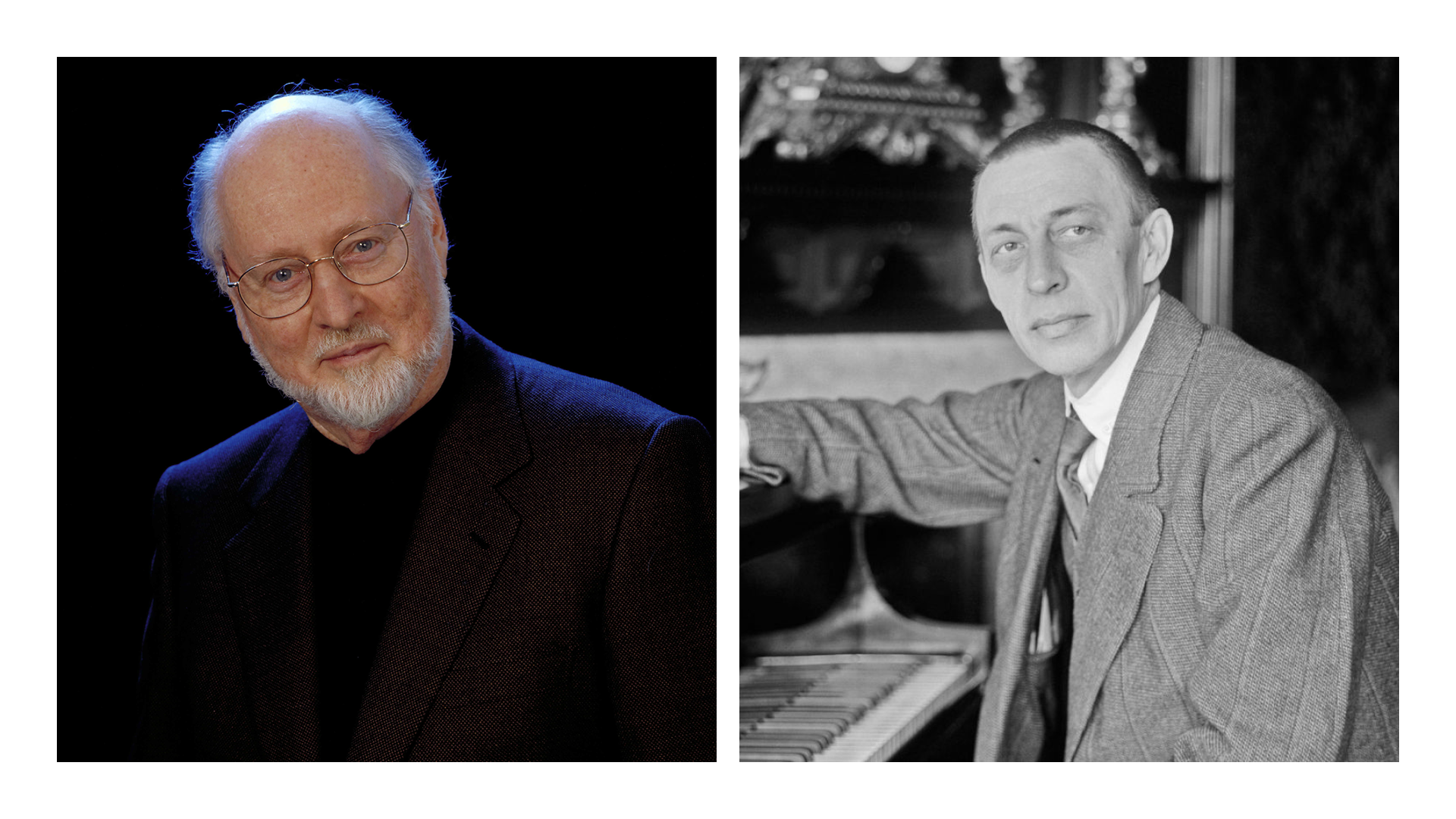

John Williams (b. 1932)

Escapades from Catch Me If You Can (1937)

Branford Marsalis, saxophone

1.Closing In

2.Reflections

3.Joy Ride

- INTERMISSION -

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943)

Symphonic Dances, Op. 45 (1940)

i.(Non) allegro

ii.Andante con moto (Tempo di valse)

iii.Lento assai — Allegro vivace

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Program Notes: Branford Marsalis with the Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Notes about:

Borodin's “Polovtsian Dances” from Prince Igor

Milhaud’s Scaramouche, Op. 165

Williams' “Escapades” from Catch Me If You Can

Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances for Large Orchestra, Op. 45

Program Notes for october 5th, 2024

Branford Marsalis with the

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Alexander Borodin

“Polovtsian Dances” from Prince Igor

Composer: born November 12, 1833, St. Petersburg; died February 27, 1887, St. Petersburg

Work composed: Borodin worked on Prince Igor from 1869-1874 and intermittently thereafter, but it remained uncompleted at the time of his death. Borodin’s friend and colleague, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, orchestrated the Polovtsian Dances.

World premiere: Eduard Nápravnik led the first performance of Prince Igor on November 16, 1890, at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg

Instrumentation: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes (1 doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, glockenspiel, snare drum, suspended cymbal, tambourine, triangle, harp, and strings

Estimated duration: 14 minutes

Alexander Borodin, like the other members of the Kucha, or Mighty Five, wrote music in his spare time. (A music critic coined the nickname “The Kucha” in reference to a group of influential 19th century Russian composers based in St. Petersburg. In addition to Borodin, the group included Mily Balakirev, César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov). A chemist by profession, Borodin made significant contributions to both his profession and his avocation.

The Kucha aspired to create authentically Russian music, free from the domination of German aesthetics. To this end, the Kucha featured indigenous folk songs and dances from different regions of the Russian empire.

Borodin employed folk dance tunes most effectively in his unfinished opera Prince Igor, the tale of 12th-century prince Igor Sviatoslavich’s failed attempt to stop the invasion of the Polovtsian Tatars in 1185. In the opera’s second act, Igor and his son are captured and held in the Polovtsian military camp. To pass the time, the Polovtsians sing and dance for the captive Russians.

The opera Prince Igor has had a fitful performance history, but the ballet sequence known as the “Polovtsian Dances” quickly became a stand-alone orchestral piece, and Borodin’s most popular and most performed music.

In 1953, the Tony award-winning musical Kismet debuted on Broadway; two years later, MGM adapted it for film. Much of the music from Kismet was derived from Borodin’s music, including the “Polovtsian Dances,” and both musical and film versions introduced Borodin to new audiences. One of Borodin’s most unforgettable melodies became Kismet’s signature hit song, “Stranger in Paradise.”

Darius Milhaud

Scaramouche, Op. 165

Composer: born September 4, 1892, Marseilles; died June 22, 1974, Geneva

Work composed: 1935-37. Originally written for two pianos. Milhaud subsequently arranged Scaramouche for alto saxophone and orchestra. At Benny Goodman’s request, Milhaud also produced a version for clarinet and orchestra.

World premiere: 1937, at the Paris International Exposition.

Instrumentation: solo alto saxophone, 2 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, bass drum, castanets, cymbals, snare drum, and strings

Estimated duration: 11 minutes

In 1937, French pianist Marguerite Long asked her friend and colleague Darius Milhaud to compose a two-piano duet for her students to perform at the Paris International Exposition. Milhaud complied, repurposing some music he had written for a production of Moliere’s play Le médecin volant (The Flying Doctor) for the first and third movements. The central slow section of Scaramouche is another recycled work, an overture Milhaud wrote in 1936 for a French play based on the life of Simón Bolívar. (Milhaud, fascinated by the life of the man South Americans nicknamed “El Libertador,” also made Bolívar the subject of his third opera. However, none of the music Milhaud wrote for the play, including the excerpt that became the second movement of Scaramouche, ended up in the opera).

Scaramouche, one of the central characters from Renaissance Italy’s Commedia dell’arte, is most often portrayed as clown who specializes in pranks. Although the music for Milhaud’s Scaramouche derives from previously composed works, the ebullience and merriment of Scaramouche’s character permeates the music, particularly the final movement, in which infectious Brazilian samba rhythms support a delightfully cheeky melody.

Composers are not always the best judges of their own work. Camille Saint-Saëns refused to allow Carnival of the Animals to be published during his lifetime, because he didn’t want his reputation as a serious composer tarnished by what he considered a musical trifle. Today, of course, Carnival of the Animals is Saint-Saëns’ most performed and best-known works, and it has been delighting audiences for more than 100 years. Similarly, Milhaud thought little of Scaramouche, and urged his publisher to ignore it. Fortunately, the publisher did not listen to his client, and Scaramouche became immensely popular. Today it is one of the most-performed piano duets in the repertoire, and its many arrangements for soloist and orchestra attest to its enduring charm.

John Williams

“Escapades” from Catch Me If You Can

Composer: born February 8, 1932, Flushing, Queens

Work composed: 2002

World premiere: The film Catch Me If You Can with Williams’ score premiered on December 25, 2002

Instrumentation: 3 flutes, 2 oboes, 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 2 trombones, bass trombone, tuba, timpani, percussion, piano/celeste, harp, and strings

Estimated duration: 13 minutes

John Williams is synonymous with movie music. He became a household name with the Academy Award-winning score he wrote in 1977 for Star Wars, and he has defined the symphonic Hollywood sound ever since.

Over his career, Williams has garnered a record 54 Oscar nominations for Best Original Score, including the one he wrote for longtime collaborator Steven Spielberg’s 2002 film, Catch Me If You Can. The movie is based on Frank Abagnale’s eponymous autobiography, which details his criminal activities during the 1960s, as well as the FBI’s years-long campaign to apprehend him. Over seven years, Abagnale impersonated an airline pilot, a doctor, and a public prosecutor in the course of his successful efforts as a master conman and forger.

“The film is set in the now nostalgically tinged 1960s,” Williams writes about his music, “and so it seemed to me that I might evoke the atmosphere of that time by writing a sort of impressionistic memoir of the progressive jazz movement that was then so popular. The alto saxophone seemed the ideal vehicle for this expression ... “In ‘Closing In,’ we have music that relates to the often-humorous sleuthing which took place in the story, followed by ‘Reflections,’ which refers to the fragile relationships in Abnagale’s family. Finally, in ‘Joy Ride,’ we have the music that accompanies Frank’s wild flights of fantasy that took him all over the world before the law finally reined him in.”

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Symphonic Dances for Large Orchestra, Op. 45

Composer: born April 1, 1873, Oneg, Russia; died March 28, 1943, Beverly Hills, CA

Work composed: the summer and autumn of 1940. The published score bears the inscription: “Dedicated to Eugene Ormandy and The Philadelphia Orchestra.”

World premiere: Eugene Ormandy led the Philadelphia Orchestra on January 3, 1941

Instrumentation: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, alto saxophone, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, chimes, cymbals, drum, orchestra bells, tam-tam, tambourine, triangle, xylophone, piano, harp, and strings

Estimated duration: 35 minutes

Sergei Rachmaninoff had great regard for the Philadelphia Orchestra and its music director, Eugene Ormandy. As a pianist, he had performed with them on several occasions, and as a composer, he appreciated the full rich sound Ormandy and his musicians produced. Sometime during the 1930s, Rachmaninoff remarked that he always had the unique sound of this ensemble in his head while he was composing orchestral music: “[I would] rather perform with the Philadelphia Orchestra than any other of the world.” When Rachmaninoff began working on the Symphonic Dances, he wrote with Ormandy and the orchestra in mind. Several of Rachmaninoff’s other orchestral works, including the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini and the Piano Concerto No. 4, were also either written for or first performed by Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra.

The Symphonic Dances turned out to be Rachmaninoff’s final composition. Although not as well-known as the piano concertos or the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Rachmaninoff himself and many others regard the Symphonic Dances as his greatest orchestral work. “I don’t know how it happened,” the composer remarked. “It must have been my last spark.”

Nervous pulsing violins open the Allegro, over which the winds mutter a descending minor triad (three-note chord). The strings set a quickstep tempo, while the opening triad becomes both the melodic and harmonic foundation of the movement as it is repeated, reversed and otherwise developed. The introspective middle section features the first substantial melody, sounded by a distinctively melancholy alto saxophone. The Allegro concludes with a return of the agitated quickstep and fluttering triad.

Muted trumpets and pizzicato strings open the Andante con moto with a lopsided stuttering waltz, followed by a subdued violin solo. This main theme has none of the Viennese lightness of a Strauss waltz; its haunting, ghostly quality borders on the macabre suggestive of Sibelius’ Valse triste or Ravel’s eerie La valse. Rachmaninoff’s waltz is periodically interrupted by sinister blasts from the brasses.

In the Lento assai: Allegro vivace, Rachmaninoff borrows the melody of the Dies irae (Day of Wrath) from the requiem mass. Rachmaninoff had used this iconic melody many times before, most notably in Isle of the Dead and the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. In the Symphonic Dances, the distinctive descending line has even more suggestive power; we can hear it as Rachmaninoff’s final statement about the end of his compositional career. This movement is the most sweeping and symphonic of the three and employs all the orchestra’s sounds, moods, and colors. In addition to the Dies irae, Rachmaninoff also incorporates other melodies from the Russian Orthodox liturgy, including the song “Blagosloven Yesi, Gospodi,” describing Christ’s resurrection, from Rachmaninoff's choral masterpiece, All-Night Vigil.

On the final page of the Symphonic Dances manuscript, Rachmaninoff wrote, “I thank Thee, Lord!”

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com