Program Notes: Scheherazade & Márquez’s Fandango

Notes about:

Margaret Bonds: Selections from The Montgomery Variations

Arturo Márquez: Fandango

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: Scheherazade

Program Notes for February 13 & 14, 2026

Margaret Bonds

The Montgomery Variations

Composer: Born March 3, 1913, Chicago, Illinois; died April 26, 1972, Los Angeles, California.

Composed: 1963-1964.

Premiere: Though there are some indications that it may have boon performed in 1967, the definitive world premiere was on December 6, 2018, by the University of Connecticut Symphony Orchestra. The Montgomery Variations was finally published in 2020.

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (1 doubling piccolo and alto flute), 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, triangle, cymbals, wood block, tambourine, large drum, harp, and strings

Duration: 15:00.

Background

Composer and pianist Margaret Bonds was born in Chicago, into a family prominent in the African American community. After her father, a well-respected physician, and mother divorced, she grew up in her mother’s house, surrounded by music...and by many of the leading Black intellectual figures and musicians of the day. In the 1920s and 1930s, there was a Chicago Renaissance in parallel to the well-known Harlem Renaissance, and the home of Margaret’s mother, Estelle Bonds, became a gathering-spot for prominent writers, artists, and musicians. Among the longterm houseguests was composer Florence Price, with whom Bonds later studied composition. She entered Northwestern University at age 16, and though she earned Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees there, she found the environment to be racist and hostile. According to Bonds, what saved her was encountering the poem The Negro Speaks of Rivers by Langston Hughes (1902-1967):

Because in that poem he tells how great the black man is. And if I had any misgivings, which I would have to have—here you are in a setup where the restaurants won’t serve you and you’re going to college, you’re sacrificing, trying to get through school—and I know that poem helped save me.

Bonds later struck up a close friendship with Hughes, and set several of his works to music, including a Christmas cantata, The Ballad of the Brown King (1960). While still at Northwestern, Bonds’s composition Sea Ghost won a national prize, and in 1933, she performed as a piano soloist with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (the first Black soloist in the orchestra’s history). In 1939, she moved to New York City, where she would spend most of her career. Bonds studied piano and composition at the Julliard School, but was also obliged to earn a living, later recalling: “no job was too lousy; I played all sorts of gigs, wrote ensembles, played rehearsal music, and did any chief cook and bottle washer job just so I could be honest and do what I wanted.” What she wanted to do, clearly, was to make music, and over the next three decades she was successful as a composer, but also as a performer, promoter, educator, community leader, and advocate for Black music. The death of Langston Hughes in 1967 seems to have been an emotional turning-point for Bonds, and she moved to Los Angeles in 1968 to work as an educator. She died there in 1972, just a few weeks after the successful premiere of her Credo by the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Montgomery, Alabama was one of the epicenters of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. One of the defining events was the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955-56, sparked by activist Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat to a white rider on a segregated Montgomery bus. This marked one of the first great victories of the movement, ending in the official desegregation of Montgomery’s buses. One of the leaders of the boycott was the pastor of Montgomery’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Martin Luther King Jr. In 1957, King (to whom Bonds would later dedicate The Montgomery Variations) and other church leaders created the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which would become a major force in the nonviolent civil rights struggle.

In 1963, Bonds was on a concert tour to Montgomery and the surrounding area and was deeply inspired by King and the movement. She began work on The Montgomery Variations, one of her very few purely orchestral pieces almost immediately finishing after the dark day of September 15. She completed the orchestration in 1964. A noted scholar of African-American music, Tammy Kernodle, describes The Montgomery Variations as follows:

The thematic narrative of the work follows the chronology of 1955 to 1963, which correlates with the initiation of the Montgomery bus boycott, the rise of Dr. King, and the initiation of nonviolent direct-action campaigns throughout the South. Bonds ends the narrative framework with one of the seminal events of the Movement—the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, on September 15, 1963, which killed four little girls, and its aftermath of grief. Coming only two weeks following Dr. King’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the bombing signified the start of a period of overt violence that pervaded the movement during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

What You’ll Hear

The Montgomery Variations is in seven movements, four of which are played here. Black spirituals have been a touchstone for many African-American composers throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, and the primary musical theme, heard throughout, is the spiritual, I Want Jesus To Walk With Me.

Bonds describes the action in the opening movement, I. The Decision: “Under the leadership of Martin Luther King, Jr., and SCLC, Negroes in Montgomery decided to boycott the bus company and to fight for their rights as citizens.” After a dramatic pair of drum rolls, the spiritual theme is laid out by the brasses. The music of this brief introduction conveys a clear sense of resolve throughout. II. Prayer Meeting is much more hushed and fervent, throughout, climaxing in a subdued brass passage and a bluesy trombone solo. Describing III: March, Bonds wrote: “The Spirit of the Nazarene marching with them, the Negroes of Montgomery walked to their work rather than be segregated on the buses. The entire world, symbolically with them, marches.” This is quietly defiant music beginning with a solo bassoon above an insistent string rhythm, that swells inexorably at the end as ever more marchers join in. About the final movement, VII. Benediction, Bonds wrote: “A benign God, Father and Mother to all people, pours forth Love to His children—the good and the bad alike.” This final section starts quietly, almost wistfully, with a series of woodwind solos, eventually growing to a grand transformation of the spiritual theme, and a quiet prayerful ending.

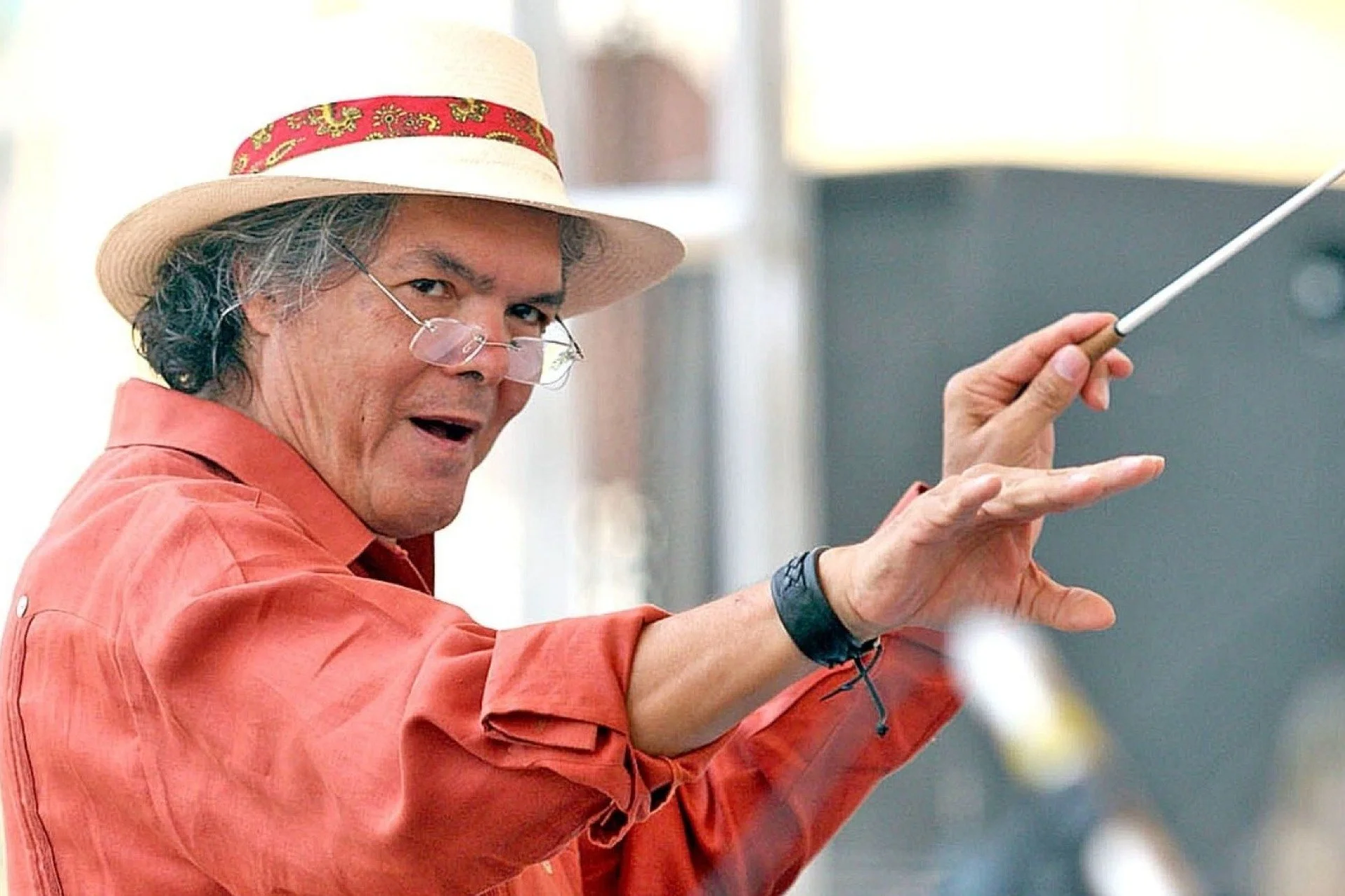

Arturo Márquez

Fandango

Composer: Born December 20, 1950, Álamos, Mexico.

Work composed: 2020. Commissioned for Anne Akiko Myers.

World premiere: In Los Angeles, on August 24, 2021, by violinist Anne Akiko Myers, with the Los Angeles, Philharmonic, led by Gustavo Dudamel.

Instrumentation: solo violin, piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, bass, trombone, tuba, timpani, snare drum, cymbals, bass drum, claves, cajon, güiro, harp, and strings.

Estimated duration: 30:00.

Background

Arturo Márquez, one of Mexico’s most successful contemporary composers, was born in the state of Sonora. When he was 12 years old, his family moved to a suburb of Los Angeles, where he studied piano, violin, and trombone. Márquez later recalled that “My adolescence was spent listening to Javier Solis [the famous Mexican singer/actor], sounds of mariachi, the Beatles, Doors, Carlos Santana and Chopin.” He later studied at the Conservatory of Music of Mexico, with the great French composer Jacques Castérède in Paris, and at the California Institute of the Arts. He is on the faculty of the National Autonomous University in Mexico City. Márquez frequently uses Mexican and other Latin folk influences in his works, and his best-known series of works are the Danzónes he began composing in the 1990s for orchestra and other ensembles.

Márquez notes regarding the Fandango that:

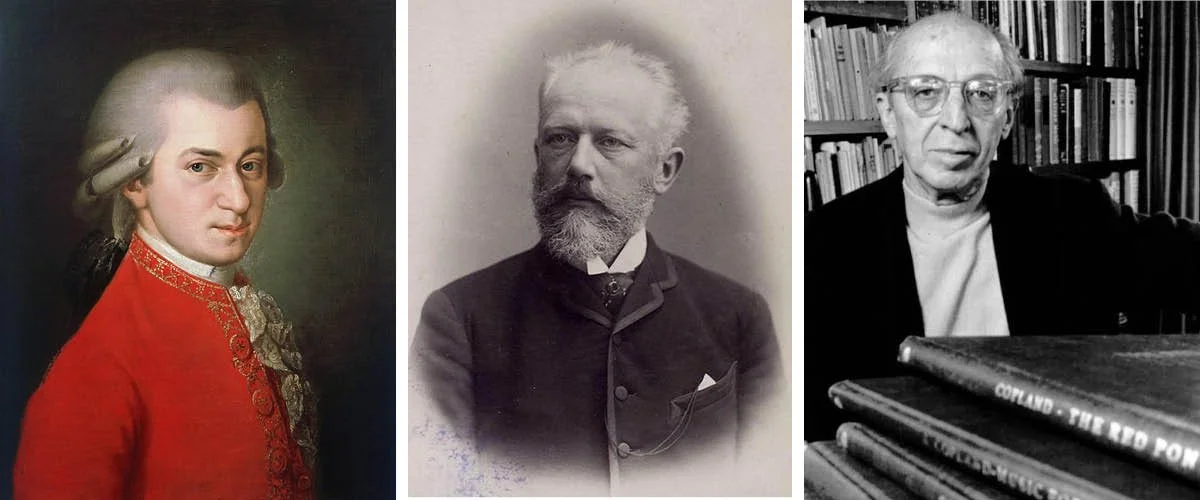

The Fandango is known worldwide as a popular Spanish dance and specifically, as one of the fundamental parts (Palos) of Flamenco. Since its appearance in the 18th century, various composers such as S. de Murcia, D. Scarlatti, L. Bocherini, Padre Soler, and W. A. Mozart, among others, have included the Fandango in concert music. What is little known in the world is that immediately upon its appearance in Spain, the Fandango moved to the Americas where it acquired personalities according to the land that adopted and cultivated it. Today, we can still find it in countries such as Ecuador, Colombia and Mexico—in the latter specifically in the state of Veracruz and in the Huasteca area, part of seven states in eastern Mexico. Here the Fandango acquires a tinge different from the Spanish genre; for centuries, it has been part of a special festival for musicians, singers, poets and dancers. Everyone gathers around a wooden platform to stamp their feet, sing and improvise ten-line stanzas bout the occasion.

In 2018 I received an email from violinist Anne Akiko Meyers, a wonderful musician, where she proposed to me the possibility of writing a work for violin and orchestra that had to do with Mexican music. The proposal interested and fascinated me from that very moment, not only because of Maestra Meyers’s emotional aesthetic proposal but also because of my admiration for her musicality, virtuosity and, above all, for her courage in proposing a concerto so out of the ordinary. I had already tried, unsuccessfully, to compose a violin concerto some 20 years earlier with ideas that were based on the Mexican Fandango. I had known this music since I was a child, listening to it in the cinema, on the radio and hearing to my father (Arturo Márquez Sr.), a mariachi violinist, play Huastecos and mariachi music. Also, since the 1990s I have been admiring the Fandango in various parts of Mexico. I would like to mention that the violin was my first instrument when I was 14 years old (1965). Remarkably, I studied it in La Puente, California in Los Angeles County where this work will be premiered with the wonderful Los Angeles Philharmonic under the direction of Gustavo Dudamel, whom I admire very much. This is a beautiful coincidence, as I have no doubt that the Fandango was danced in California in the 18th and 19th centuries.

What You’ll Hear

Márquez provides the following description of the work itself:

Fandango for violin and orchestra is formally a concerto in three movements:

Folia Tropical

Plegaria (Prayer) (Chaconne)

Fandanguito

The first movement, Folia Tropical, is in the sonata form of a traditional classical concerto: introduction, exposition with its two themes, bridge, development and recapitulation. The introduction and the two themes share the same motif in a totally different way. Emotionally, the introduction is a call to the remote history of the Fandango; the first theme and the bridge, this one totally rhythmic, are based on the Caribbean “Clave” rhythm, and the second is eminently expressive, almost like a romantic Bolero. Folias are ancient dances that come from Portugal and Spain. However, also the root and meaning of this word also takes us to the French word “folie”—madness.

The second movement Plegaria pays tribute to the Huapango mariachi together with the Spanish Fandango, both in its rhythmic and emotional parts. It should be noted that one of the Palos del Flamenco Andaluz is known as the Malagueña and Mexico also has a Huapango honoring the Andalusian city of Malaga. I do not use traditional themes but there is a healthy attempt to unite both worlds; that is why this movement is the fruit of an imaginary marriage between the Huapango mariachi and Pablo Sarasate, Manuel de Falla and Issac Albeniz, three of the Spanish composers whom I most love and admire. It is also a freely treated Chaconne. Perhaps a few people know that the Chaconne as well as the Zarabanda were two dances forbidden by the Spanish Inquisition in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, long before they became part of European Baroque music. Moreover, the first written descriptions of these dances place them in colonial Mexico of these centuries.

The third movement, Fandanguito, is a tribute to the famous Malaga huasteco. The music of this region is played by violin, jarana huasteca (small rhythm guitar) and huapanguera (low guitar with 5 courses of strings). This ensemble accompanies the songs and recited or sung improvisation. The huasteco violin is one of the instruments with the most virtuosity in all of America. Its technique has certain features similar to Baroque music but with great rhythmic vitality and a rich original variety in bow strokes. Every huasteco violinist must have a personal version of this playing technique, if he wants to have and maintain prestige. This third movement is a totally free elaboration of the Fandanguito huasteco, but it maintains many of its rhythmic characteristics. It demands great virtuosity from the soloist. It is music that I have kept in my heart for decades.

I think that for every composer it is a real challenge to compose new works from old forms, especially when this repertoire is part of the fundamental structure of classical music. On the other hand, composing in this during the 2020 pandemic was not easy due to the huge human suffering. Undoubtedly my experience with this work during this period has been intense and highly emotional but I must mention that I have preserved my seven capital principles: tonality, modality, melody, rhythm, imaginary folk tradition, harmony and orchestral color.

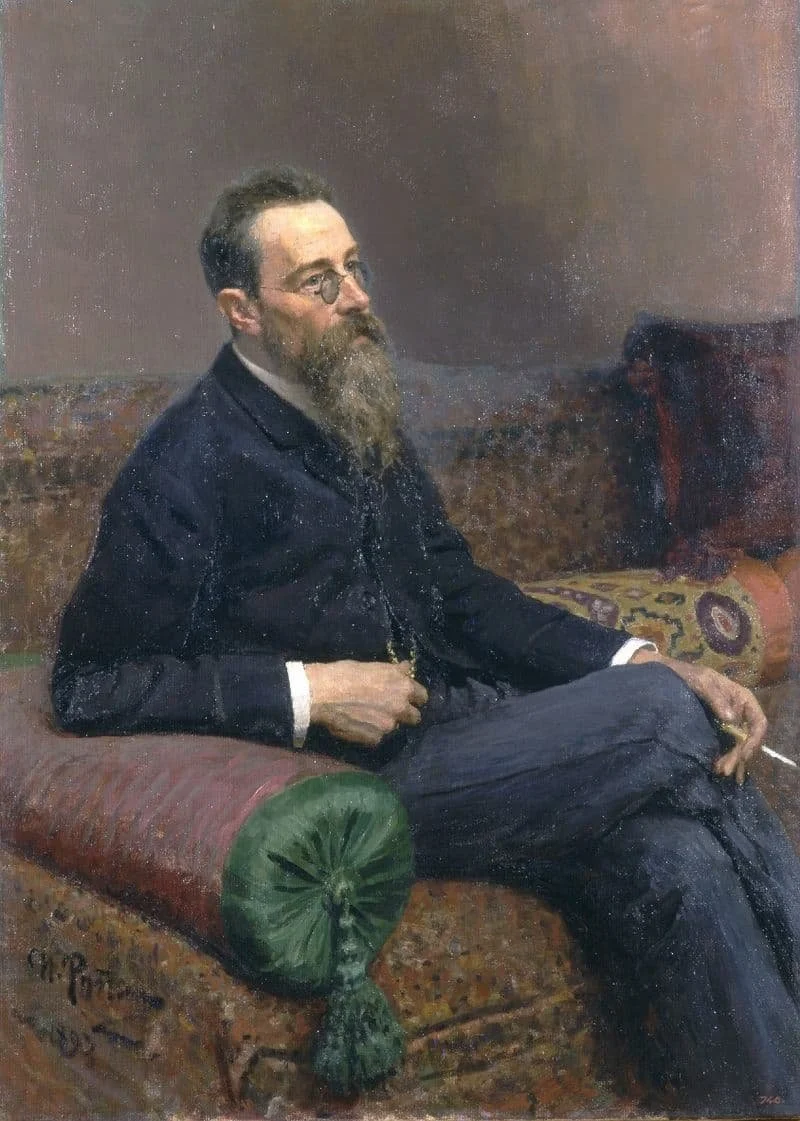

Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908)

Scheherazade: Symphonic Suite, Op. 35

Composer: Born March 18, 1844, in Tivkin, Russia; died June 21, 1908, in Liubensk, Russia.

Work composed: Rimsky-Korsakov completed Scheherazade in 1888, during his summer break from his duties at the St. Petersburg Conservatory.

World premiere: The composer conducted its premiere in St. Petersburg, on November 9, 1888.

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (2 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, cymbals, suspended cymbal, snare drum, triangle, tambourine, tamtam, harp, and strings.

Approximate duration: 40:00.

Background

The Thousand and One Nights is a collection of Arabic and Egyptian stories dating from as early as the 10th century. The framing story is that the Sultan Shahryar, convinced of the infidelity of all women, puts a series of wives to death until the Princess Scheherazade distracts him by telling him one fantastic tale after another, one each night for 1001 nights. He eventually lays aside his murderous plan. There are many versions of The Thousand and One Nights, but most of the stories, including the voyages of Sinbad and the story of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, were collected together by the 15th century. Some, including, the story of Aladdin, were added even later. 19th-century readers were fascinated by exotic settings and fairy-tales and the “Arabian Nights” fills this bill nicely—stories of love, humor, bravery, and magic. To be sure, most European, American, and Russian readers knew the collection only through carefully-edited translations that avoided the more sexually explicit bits, and accentuated the fairy-tale aspects. (An exception was the unexpurgated English translation published by Francis Burton in 1885—a highly controversial book in its time.) The tales served as the basis for innumerable works of art, literature, dance and music. The most powerful musical treatment is certainly Rimsky-Korsakov’s symphonic suite Scheherazade, which was composed in 1888.

Rimsky-Korsakov, the great Russian nationalist and leading teacher at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, first conceived of a work on stories from The Thousand and One Nights in the winter of 1887 as he was at work on his completion of Borodin’s Prince Igor. He finished Scheherazade in 1888, during his summer break from his teaching duties—at roughly the same time as he completed his equally famous Russian Easter Overture. In the earliest version, Rimsky-Korsakov gave descriptive titles to Scheherazade’s four sections: I. The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship, II. The Tale of the Kalendar Prince, III. The Young Prince and the Young Princess, and IV. Festival at Bagdad. The Sea. The Ship Goes to Pieces on a Rock Surmounted by the Bronze Statue of a Warrior. Conclusion. He was uncomfortable with a strictly programmatic interpretation, however, and before publishing the work, considered replacing the titles of the four movements with less picturesque designations: Prelude, Adagio, Ballade, and Finale. Rimsky-Korsakov did away with movement-titles altogether in the published version of the suite, but by this time the original descriptive titles were well known. He actually managed to have it both ways, however, as he later wrote in his autobiography:

In composing Scheherazade, I meant these hints to direct but slightly the hearer’s fancy on the path which my own fancy had traveled, and to leave more minute and particular conceptions as to the will and mood of each movement. All that I desired was that, if the listener liked my piece as symphonic music, he should carry away the impression that it is beyond doubt an oriental narrative of some varied fairy-tale wonders, and not merely four pieces played one after the other, and composed on the basis of themes common to all of the four movements. Why then, if this is the case, does my suite bear the specific title of Scheherazade? Because this name and the title The Arabian Nights connote in everybody’s mind the East and fairy-tale marvels—besides, certain details of the musical exposition hint at the fact that all of these are various tales of some one person (which happens to be Scheherazade) entertaining therewith her stern husband.

What You’ll Hear

Rimsky-Korsakov was an acknowledged master of scoring music for orchestra (his Principles of Orchestration is still one of the standard works on the subject)—for him, “orchestration is part of the very soul of the work.” Scheherazade may well be his masterwork in this regard—are few other works that make such effective use of orchestral color. The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship begins with a pair of themes that recur in all four movements, an angry theme from the trombones (the voice of the Sultan?) and a seductive violin solo, which despite all of Rimsky-Korsakov’s circumlocutions, must represent Princess Scheherazade herself. The body of the movement is distinctly aquatic, with a broad 6/4 theme that suggests the rolling of the waves.

There are several princes in the collection who disguise themselves as kalendars—roving holy men. After the violin announces a new story, Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Tale of the Kalendar Prince begins with a series of quiet, oriental-sounding woodwind solos, expanding into a dance for the full string section. A bold pronouncement from the solo trombone suddenly changes the mood, and the movement ends in what sounds like an extended battle scene, alternating Scheherazade’s theme with more warlike music. The next movement is a gentle contrast: The Young Prince and the Young Princess is a nostalgic interlude, with a rich dance melody (derived from Scheherazade’s theme) above a shimmering background, and a hint of oriental percussion. Scheherazade herself appears briefly, before the movement ends with a lush coda.

The finale begins with boisterous and sometimes frantic festival music that alternates with Scheherazade’s sinuous theme. The broad Sinbad music of the first movement returns in the trombones, but now the woodwinds provide the howling of hurricane winds, until a moment of crashing disaster. The movement ends with a quiet epilogue for solo violin, as Scheherazade concludes the tale.

Program notes ©2026 J. Michael Allsen

Program Notes: Beethoven & Klebanov

Notes about:

Beethoven: Violin Concerto in D Major

Klebanov: Symphony No. 1

Williams: A Prayer for Peace

Program Notes for November 14 & 15, 2025

Beethoven & Klebanov

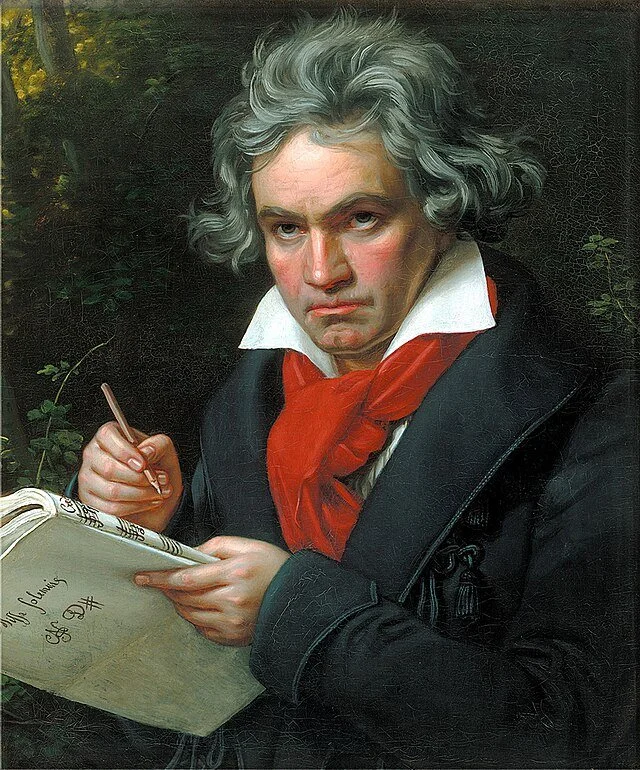

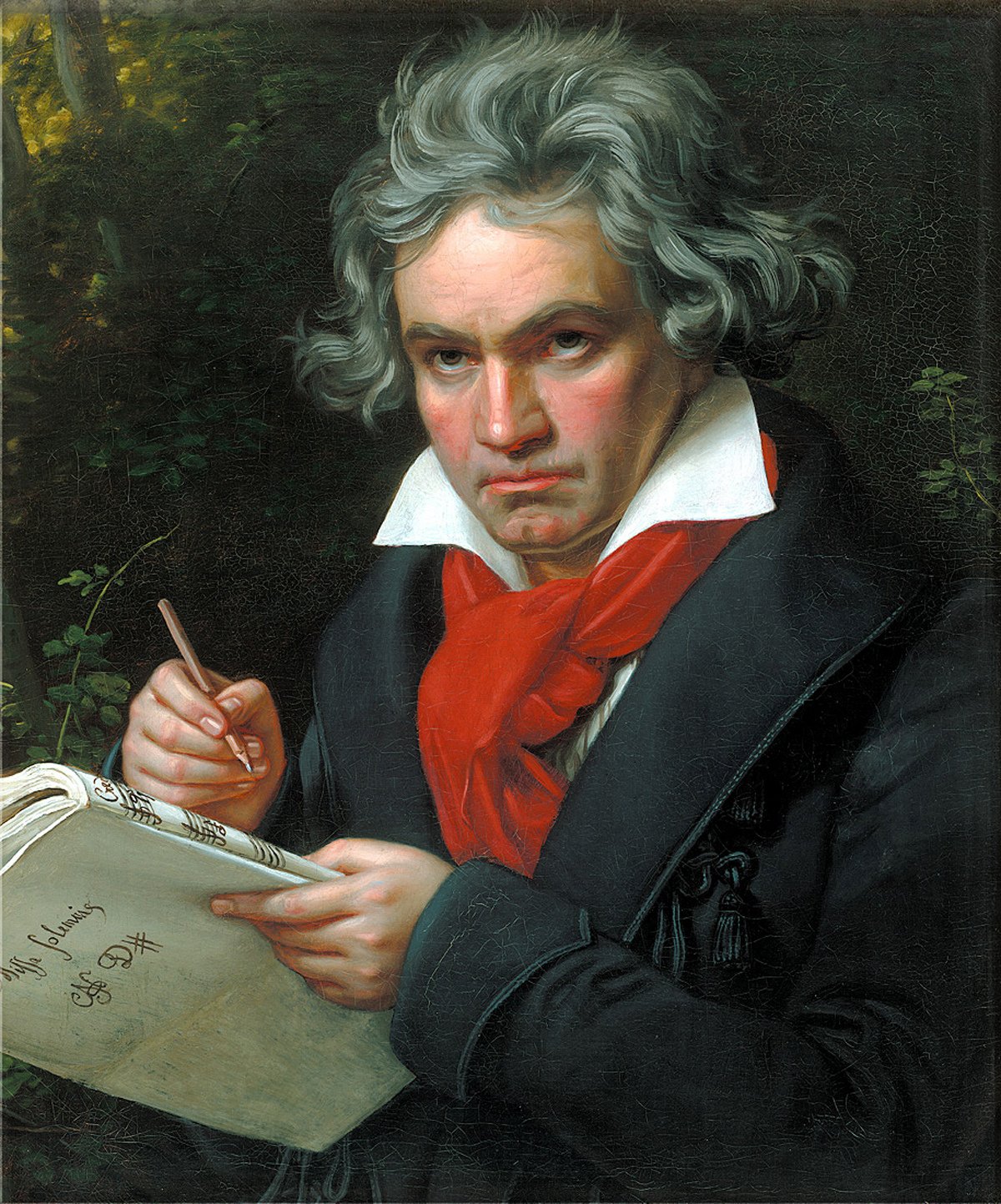

Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Concerto in D Major for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 61

Beethoven composed this concerto in 1806, and it was first performed on December 23, 1806, at the Theater-an-der-Wien in Vienna, with Franz Clement as soloist.

Duration: 39 minutes

Background

Beethoven completed his only concerto for violin in 1806, during a burst of creativity that also produced the three “Razumovsky” quartets, the fourth symphony, the “Appassionata” sonata, and the fourth piano concerto. The concerto was written for Franz Clement, a violinist whose association with Beethoven went back to 1794, when Clement was a 14-year-old Wunderkind. The title page dedicates the work to Clement, while noting his “clemency” towards the composer. (Beethoven’s puns were even worse than the normal lot.) The concerto was premiered at a concert that apparently included some pretty flamboyant showmanship. According to a review of the concert in the Wiener Theater-Zeitung, Clement inserted one of his own violin sonatas between the first and second movements of the concerto—a sonata played on one string, with the violin held upside-down! Perhaps because of this blatant showstopper, reviews of the performance were generally disdainful. (The fact that Clement was reportedly sight-reading the concerto may not have helped, either...)

This was not a work that caught on quickly, and it certainly did not follow the fashion of the time. By 1806, audiences were beginning to demand works that displayed astonishing feats of speed and agility: flash over substance. Even as late as 1855, when a young Joseph Joachim played Beethoven’s concerto for the virtuoso Louis Spohr, Spohr’s reaction was: “This is all very nice, but now I’d like you to play a real violin work.” Beethoven’s concerto is more symphonic in scope, focusing on careful development of his broad and profound themes, and brilliant orchestration, instead of empty virtuosity. The concerto finally came into its own in the later 19th century, as players like Joachim confronted the special challenges of Beethoven’s work: thoughtfulness and musical expression.

What You’ll Hear

The first movement (Allegro ma non troppo) begins with five unaccompanied timpani notes that usher in the woodwinds. The orchestral introduction presents the themes that will provide the raw material for the solo violin’s more extensive treatment. At the close of the introduction, the orchestra hushes and allows the opening violin line to burst forth—a flourish that spans the entire range of the instrument. The body of this movement is based on a set of beautiful hymn-like themes. The violin’s expansion of these melodies is never merely flashy decoration, but instead careful development. A lengthy cadenza leads to a final statement of the second main theme.

The Larghetto is certainly one of the most intriguing and expressive of Beethoven’s compositions. Its form has variously been described as “theme and variations,” “semi-variations” and even “strophic.” In a classic essay, Beethoven scholar Owen Jander suggested that the deliberate ambiguities in the overall theme and variations form of the Larghetto reflect a burgeoning Romanticism—that the slow movement is a musical rendering of a poetic dialogue. In fact, the movement proceeds in a gentle but passionate dialogue between the soloist and the orchestra, culminating in a dramatic cadenza that leads directly into the final movement.

The last movement is more typical of Classical style—a spirited 6/8 Rondo. Here, it seems, Beethoven made a slight bow to audience demand and gave the violinist some flashier technical passages. There is a brief minor-key episode at the center, but otherwise the mood of this concerto is exuberant throughout. The concerto closes with an extended coda that gives the violinist one more chance at some soloistic fireworks.

Program Notes ©2025 J. Michael Allsen

Dmitri Klebanov

Symphony No. 1 “In Memoriam Babi Yar”

Dmytro Lvovich Klebanov was born in 1907 to a working-class Jewish family in Kharkiv, Ukraine. A musical prodigy, he enrolled at the Kharkiv Conservatory at age 16, where he would later return as professor of composition (and where he would meet his wife Nina, the conservatory director). His burgeoning reputation as a composer in the Soviet Union in the 1930s speaks to his talent and tenacity at a time when Stalin’s government was targeting and disappearing Ukrainian artists and intellectuals—a period known as the Executed Renaissance.

When the Nazi army invaded Ukraine in 1941, Klebanov and his family, along with thousands of other Soviet Jews, were relocated to Uzbekistan; they returned home in 1944 to find horrific destruction and loss of life, including Klebanov’s brother, a soldier in the Soviet army. With this backdrop, Klebanov immediately began work on his First Symphony, dedicating it to the victims of the September 1941 massacre of nearly 34,000 Jews at the hands of the occupying Nazis at the Babi Yar ravine in Kyiv (some 17 years later, Babi Yar would also be the theme of Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 13).

Klebanov’s Symphony No. 1 premiered in 1946 in Kharkiv, and its public success moved it to be submitted for the 1949 Stalin Prize. The score’s arrival in Moscow, however, led not to commendation, but condemnation: Stalin’s cultural authorities connected the symphony’s dedication to its Jewish melodic influences, and claimed that by using such sources, Klebanov had “unpatriotically” and “insolently” dedicated it specifically to Jewish, rather than Soviet, victims of the massacre.

Any additional performances of the symphony were canceled, and Klebanov found himself blacklisted. His wife’s stature as conservatory director likely saved him from deportation or worse, but a ruling by the Union of Soviet Composers stripped him of his titles as Head of the Kharkiv Conservatory’s Composition Department and as Chair of the local Composers’ Union. Klebanov was allowed to remain at his post in Kharkiv, but was he effectively shunned and isolated. He would not hear his symphony again before his death in 1987.

From its first notes, the symphony invokes a curious specter: Beethoven’s famous Ninth Symphony, with its descending fourths and fifths over a rustling bed of tremolando strings. At the same time, this first theme conjures an image of falling, as if into the Babi Yar ravine itself. A gentler, nostalgic second theme is introduced in contrast, based on the opposite motion of a rising fourth.

The Scherzo second movement opens with mysterious celli and basses and soon becomes a rousing, brutal dance in 3/4 time. A romantic arioso theme for the violins opens the middle Trio section, which slowly builds to a raucous climax and settles back to a softer sequence of yearning woodwind solos.

The third movement, a funeral march, recalls the nostalgic second theme of the first movement with its rising fourth, now a dark and somber solo for the bass clarinet. An animated, ferocious middle section summons the first theme of the first movement once again, before a final, grand statement of the Funeral March theme collapses into the most evocative moment of the symphony: the March theme, sung wordlessly by a contralto vocal solo. The ghost of a synagogue cantor, perhaps—a victim of the massacre.

The Finale erupts in a bombastic paraphrase of the Presto Finale of Beethoven’s Ninth, leading to a series of cello-bass recitatives interspersed with recollections of previous movements of the symphony—again, the same architecture as Beethoven’s finale. Klebanov’s recitatives have a singspeak-like intonation that seems to evoke a Hebrew recitation: the Mourner’s Kaddish prayer, perhaps. An English horn solo emulates a shofar, the traditional ram’s horn blown during the Jewish High Holidays.

Klebanov then builds a tightly-constructed fugue, its boisterous subject built around the intervals of the recitative motif, which leads to a reprise of the opening Presto. What follows can only be described as a satire of the Ode to Joy itself, introduced with soft celli and basses in the same way Beethoven presents his famous melody. Klebanov’s mock-Ode theme undergoes a series of dramatic variations before ending up a militaristic trumpet duet punctuated by orchestral cannon fire. The recitative returns, now in an aggressive, off-kilter ostinato, which leads finally to the coda: the return of the first movement “Babi Yar” theme, now rising victoriously as an exuberant brass fanfare, in conversation with the Hebraic recitative in the low voices below.

It does not strain the imagination to interpret these references to Beethoven as an act of defiance against Ukraine’s erstwhile invaders, holding up a mirror to the Germanic music the Nazis once touted as proof of their own superiority while juxtaposing it against Jewish-inspired melodies. “Despite their atrocities against our people,” the subtext might read, “we are still here.”

Program Notes written by Music Director Nicholas Hersh

Program Notes: Williams & Rachmaninoff

Notes about:

Williams: Concerto for Cello & Orchestra

Rachmaninoff: Symphony No. 2 in E Minor

Program Notes for October 10 & 11, 2025

Williams & Rachmaninoff

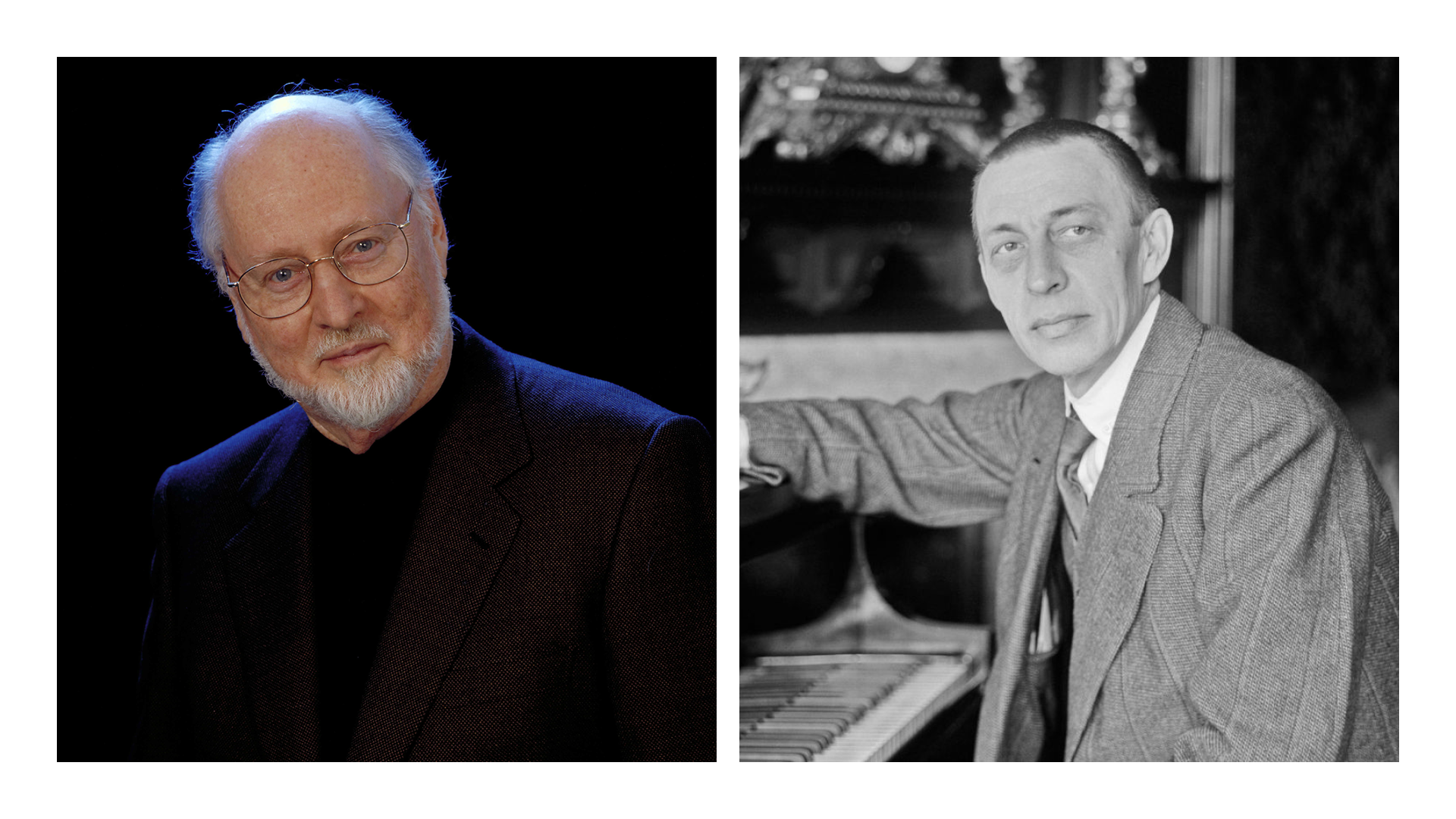

John Williams

Concerto for Cello and Orchestra

Composer: born February 8, 1932, Flushing, Queens, NY

Work composed: 1993-94. Commissioned by Seiji Ozawa and the Boston Symphony and composed for cellist Yo-Yo Ma.

World premiere: Williams led Yo-Yo Ma and the Boston Symphony on July 7, 1994, at Tanglewood, to mark the opening of Seiji Ozawa Hall.

Instrumentation: solo cello, 3 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets (1 doubling bass clarinet), 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 4 trombones, timpani, bass drum, chimes, glockenspiel, marimba, mark tree, small triangle, suspended cymbal, tam-tam, triangle, tuned drums, vibraphone, harp, piano/celesta, and strings

Estimated duration: 30 minutes

“Music is our oxygen.”

Composer John Williams is synonymous with movie music. He became a household name with the Academy Award-winning score he wrote in 1977 for Star Wars, and he has defined the symphonic Hollywood sound ever since. In addition to the Star Wars films, Williams composed the music for Jaws, the Raiders of the Lost Ark films, Superman, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T., the Jurassic Park films, Schindler’s List, the Harry Potter series, and many other films.

Williams has also composed a considerable body of concert works, including six concertos. Like his scores, Williams’ concert music also features his masterful orchestration and dramatic flourishes, and his concertos are designed to showcase the unique qualities of both the solo instrument and the soloist.

Williams and Ma have been good friends and collaborators for decades. “Given the broad technical and expressive arsenal available in Yo-Yo’s work, planning the concerto was a joy,” Williams writes. “I decided to have four fairly extensive movements that would offer as much variety and contrast as possible but that could be played continuously and without interruption.

“The Theme and Cadenza, after an opening salvo of brass, immediately casts the cello in a kind of hero’s role, making it the unquestioned center of attention. It’s a movement that attempts to put the cello on display in the time-honored sense of ‘concerto,’ and as the hero’s theme is developed, it ‘morphs’ into a cadenza in which I tried to create an opportunity for exploration of the theme that would be both ruminative and virtuosic.

“The second movement I call Blues.… In my mind, and without any conscious prodding on my part, the ghosts of Ellington and Strayhorn seemed to waft through the atmosphere. Invited or not, this was for me very welcome company. I set up clusters in piano and percussion that form a frame within which the cello unveils its misty quasi-improvisations.

“The Scherzo is about speed, deftness, and sleight of hand. The music romps along in triple time over a treacherous landscape where athletic exchanges are periodically and suddenly interrupted by a series of fermatas, as the orchestra and cello try to dominate and outdo each other. There’s a short tutti where it appears that the orchestra might prevail, but the cello outwits and outlasts it.

“In thinking about the finale of the concerto, I was always aware of the fact that Yo-Yo’s ability to ‘connect’ personally and even privately with every individual in his audience is perhaps the greatest of his abundant gifts. I therefore tried in Song, the concerto’s finale, to create long lyrical lines that would give the cello the opportunity to address the audience in the manner of a clear and direct soliloquy.

“Whatever virtues the concerto may have can never surpass, for me, the experience of knowing and working with Yo-Yo Ma. Happily, and with complete justice, the world loves and reveres this man, as do I, and working with him is always a joyous journey to be treasured.”

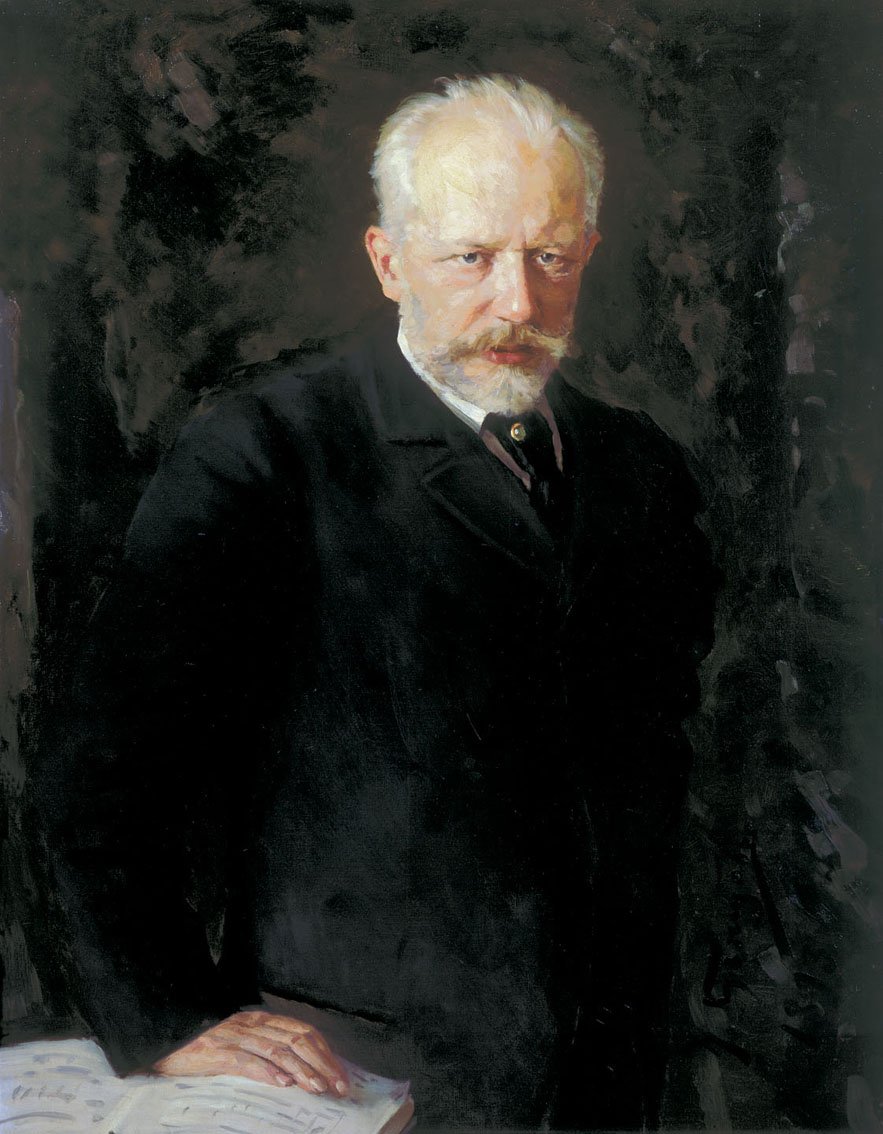

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Symphony No. 2 in E minor, Op. 27

Composer: born April 1, 1873, Oneg, Russia; died March 28, 1943, Beverly Hills, CA

Work composed: 1906-07. Rachmaninoff dedicated it to his composing teacher, Sergei Taneyev

World premiere: February 7, 1908, in St. Petersburg, with Rachmaninoff conducting

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 3 oboes (1 doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, glockenspiel, snare drum, and strings

Estimated duration: 43 minutes

Artists of all types have a love-hate relationship with critics: they need the exposure criticism brings to their work, but often scorn the critiques themselves. Other artists take criticism too much to heart and let it affect them to a debilitating degree, which was the case with Sergei Rachmaninoff. After the premiere of Rachmaninoff’s first symphony, he was so savaged by critics that he did not dare compose a note for three years. Eventually Rachmaninoff consulted a doctor, Nicolai Dahl, who used hypnotism to bolster Rachmaninoff’s flagging confidence. Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto was dedicated to Dahl, and it vindicated Rachmaninoff as a composer by becoming one of his most popular works.

After the success of the Second Piano Concerto, Rachmaninoff felt ready to tackle another symphony, and in 1906 he began work on his second. The writing was difficult for him, as he reported in a letter to a friend, and the work proceeded slowly. The final version lasted over an hour, although Rachmaninoff later suggested a number of performance cuts that shorten it by as much as 20 minutes; these cuts have become standard when programming this symphony today. Although Rachmaninoff, out of necessity, agreed to the cuts, which amounted to some 300 measures of music, he later confided to conductor Eugene Ormandy, “You don’t know what cuts do to me. It is like cutting a piece out of my heart.” Rachmaninoff might have appreciated the words of one critic, who wrote at the symphony’s premiere, “After listening with unflagging attention to its four movements, one notes with surprise that the hands of the watch have moved sixty-five minutes forward. This may be slightly overlong for the general audience, but how fresh, how beautiful it is!”

The symphony opens with a darkly murmuring theme played by the lower strings, a theme that forms the basis for the remainder of the first movement, as well as much of the rest of the symphony. The violins contrast with a lyrical melody, followed by a plaintive solo for English horn. Throughout this movement, Rachmaninoff uses solo instruments as structural signposts, indicating changes of mood or harmonic foundations.

The horns launch the Scherzo with a bold, energetic theme, and the strings continue with a bouncier, skipping melody. These are contrasted by a series of interludes, one unabashedly romantic, and others feverishly intense. As was his wont in many of his orchestral works, including the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Rachmaninoff includes the Dies irae melody (Day of Wrath) from the Requiem Mass; it appears here in the coda to the trio.

In the Adagio, Rachmaninoff’s signature romanticism is heard in the violins’ opening melody, which could easily serve as the love song in a cinematic romance. In fact, 1970s pop singer Eric Carmen wrote a hit song based on this theme, “Never Gonna Fall in Love Again.”

For the Finale, Rachmaninoff unleashes a whirlwind of vibrant joy. Buoyant strings recall the Scherzo, but this music is abruptly interrupted by the stark call of muted horns. We then hear snatches of music from previous movements, especially the Scherzo and the Adagio. The strings, playing in the style of the Italian tarantella, are the foundation for this movement, and its energy drives the symphony forward to a triumphant conclusion.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

Program Notes: Verdi's Requiem

Notes about:

Guiseppe Verdi: Requiem Mass (In Memory of Alessandro Manzoni)

Program Notes for May 9 & 10, 2025

Verdi’s Requiem

Giuseppe Verdi

Requiem

Composer: born October 9, 1813, Le Roncole, near Busseto, Italy; died January 27, 1901, Milano

Work composed: Verdi wrote the “Libera me” in 1868, in tribute to Gioachino Rossini. In the summer of 1873, Verdi resumed work on the Requiem, which he completed on April 10, 1874, and dedicated to the memory of Italian poet and patriot Alessandro Manzoni. Verdi’s original title, inscribed in the mss, reads “Requiem Mass for the anniversary of the death of Manzoni, 22 May 1874”

World premiere: Verdi conducted the first performance on May 22, 1874, in the church of St. Marco, Milano, with Teresa Stolz, Maria Waldmann, Giuseppe Capponi, and Ormondo Maini, vocal soloists.

Instrumentation: SATB soloists, four-part chorus, 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 4 bassoons, 4 horns, 4 trumpets (one offstage), 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, and strings.

Estimated duration: 83 minutes

“It was an impulse, or, to put it better, a need from my heart, to honour, as best I could, this great man whom I held in such esteem as a writer, and venerated as a man, and as a model of virtue and patriotism.” – Giuseppe Verdi’s letter to the Mayor of Milan, about the composer’s proposal to write a requiem mass to honor the memory of Italian writer, poet, and patriot Alessandro Manzoni.

“A great name has disappeared from the world! His was the most widespread, the most popular reputation of our time, and it was a glory of Italy! When the other one who still lives [Manzoni] is no more, what will we have left?” These were the words of Giuseppe Verdi upon hearing the news of Gioachino Rossini’s death, in 1868. It was Rossini’s passing that first inspired Verdi to think of composing a Requiem. Just days after Rossini died, Verdi wrote the Italian music publisher Ricordi, proposing a collaborative Requiem written by “the most distinguished Italian composers,” to honor Rossini’s memory. Verdi added many stipulations and conditions to his idea, including the suggestion that everyone involved with the Requiem should help finance it. For a number of reasons – financial, logistical, and political – the proposed Rossini memorial ceremony was shelved, although every composer who was asked to write a movement completed their assigned section on time (The Messa per Rossini did eventually receive a public performance – in 1988).

With the Rossini project scrapped, Verdi turned his creative attention elsewhere. In the years between 1869 and 1873, Verdi busied himself with his opera Aida, a commission from the Egyptian government to commemorate a new Egyptian opera house built to celebrate the 1869 opening of the Suez Canal. As Verdi conducted Aida around Europe, he also composed his E minor String Quartet, his only surviving piece of chamber music.

In the spring of 1873, Ricordi sent Verdi the score to his “Libera me.” A month later, Alessandro Manzoni, one of the most important writers, thinkers, and patriots of 19th-century Italy, died at the age of 88. Verdi, along with most Italians, venerated Manzoni almost to the point of sainthood (Verdi said of Manzoni’s 1827 masterpiece, I promessi sposi (The Betrothed), that it was “not only the greatest book of our epoch, but one of the greatest ever to emerge from a human brain.”) Both men were also deeply committed to the Risorgimento, the decades-long Italian political and social effort to unify all the Italian city-states into one Kingdom of Italy, with Rome as its capital. Verdi was not much given to hero worship generally, but the depth of his feelings for both Manzoni and Manzoni’s impact on Italian culture cannot be exaggerated.

With Manzoni’s death, Verdi returned immediately to the idea of a Requiem Mass to honor a true Italian hero. On June 3, 1873, Verdi wrote to Ricordi, “I too would like to demonstrate what affection and veneration I bore and bear to that Great Man who is no more, and whom Milan has so worthily honored. I would like to set to music a Mass for the Dead to be performed next year on the anniversary of his death. The Mass would have rather vast dimensions, and besides a large orchestra and a large chorus, it would also require … four or five principal singers … I would have the copying of the music done at my expense, and I myself would conduct the performance both at the rehearsals and in church.” Verdi further asked Ricordi to invite the Mayor of Milan to sanction this undertaking. Permission was soon granted, and Verdi quickly set to work.

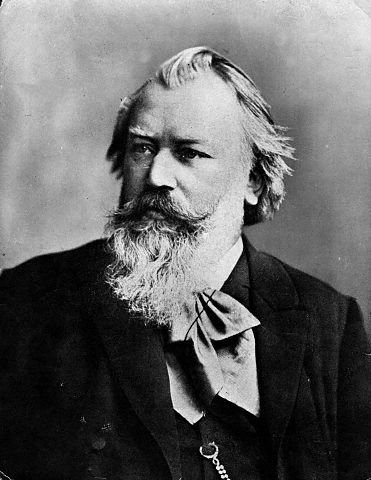

Verdi’s Requiem, like Johannes Brahms’ Ein Deutsches Requiem, is a personal statement of grief that employs structure and text borrowed from church liturgy. However, neither Verdi nor Brahms was personally devout. For both men, the texts they chose for their respective Requiems served as an expressive outlet for the universal need to convey the emotions that surface when a beloved person dies: grief, loss, sadness, anger, fear of judgment, and the hope of a lasting peace for both the departed and the bereaved. The dramatic, operatic quality of Verdi’s requiem ill-suited it for use as part of a regular church service, and Verdi never intended it to function as liturgy. From the beginning, Verdi conceived his Requiem for performance, not worship.

Conductor Hans von Bülow’s famous remark that the Requiem was “an opera in ecclesiastical costume” was meant as condemnation. However, one can take von Bülow’s words at face value, without the harsh judgment he intended. Certainly no other Requiem comes close to approaching the drama and tension of Verdi’s, and the ebb and flow of emotion it generates parallels the narrative arc of a grand opera. The obvious passion of Verdi’s music, and the operatic vocabulary he employs throughout, need not diminish the Requiem’s impact as a profound articulation of grief. For Verdi, as for his countrymen, the only way to properly mourn Manzoni and pay homage to his unique stature in Italy was through an equally significant, expansive musical statement.

The liturgy of the requiem mass is not standardized; each composer must make specific choices regarding which texts to include. Verdi begins with the standard opening lines, “Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine” (Grant them eternal rest, O Lord), which the chorus and orchestra intone in hushed, muted phases. The four soloists join the chorus and orchestra for an exuberant “Kyrie eleison” (Lord have mercy), which makes the “Dies irae” that follows all the more terrifying. This music is the most recognizable to audiences, but familiarity cannot dent its powerful impact. The sopranos and tenors sustain a high G while the lower voices, punctuated by a shrill piccolo and a pounding bass drum, warn of the Day of Wrath, when fire shall destroy the earth, according to dire prophecy. A chorus of brasses precedes the bass soloist, who describes the sound of the trumpet that will summon all to judgment. The mezzo-soprano and chorus tell of the Book of Judgment, in which all deeds are recorded, and from which the world cannot escape. The focus shifts from prophecy to first person entreaty, as the soprano, mezzo, and tenor plead in vain for clemency (Who will intercede for me when even the just are unsafe?) The Sequence, which begins with “Dies irae” and ends with “Lacrimosa” (Weeping), covers the full emotional spectrum from abject terror to gentle entreaties for mercy, as the supplicant, on bended knee, acknowledges his/her own unworthiness.

The tender opening of the Offertorio, which features the four soloists, emphasizes the mercy of Christ. Its rocking meter suggests a lullaby, and as the singers describe the “holy light” God promised to Abraham and his descendants, both the vocal and orchestral writing grow more luminous. Verdi expertly delivers us from the pits of hell (low timbres and registers) into the glowing warmth of salvation, and readies us for the untrammeled joy of the Sanctus, with its trumpet fanfare proclaiming “Holy, holy, holy, Lord of Hosts! Heaven and earth are filled with your glory!” In the Agnus Dei, Verdi shifts from extroversion to unadorned unisonal contemplation with minimal orchestral accompaniment, as first the chorus, then the soprano and mezzo sing, “Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, grant them eternal rest.” Verdi ends his Requiem with an agitated soprano intoning the opening lines of “Libera me” (Deliver me, O Lord, from eternal death on that awful day). All the drama of the earlier sections returns, as if Verdi intended to leave us with a sense of uncertainty: will we, in the final analysis, be redeemed? Verdi reprises the music of the “Dies irae,” but eventually, the chorus and soprano end with an almost inaudible whisper, “Libera me. Libera me.”

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

Program Notes: Carnival of the Animals

Notes about:

Gershwin (arr. Hersh): Three Preludes

Saint-Saëns: Carnival of the Animals

Norman: Drip Blip Sparkle Spin Glint Glide Glow Float Flop Chop Pop Shatter Splash

Copland: Four Dance Episodes from Rodeo

Program Notes for April 11 & 12, 2025

Carnival of the Animals

George gershwin

Three Preludes (arr. Hersh)

Composer: born September 26, 1898, Brooklyn, NY; died July 11, 1937, Hollywood, CA

Work composed: 1926, originally for solo piano. Dedicated to Gershwin’s friend and colleague Bill Daly

World premiere: Gershwin performed the three preludes at the Roosevelt Hotel in New York City on December 4, 1926.

Instrumentation: flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, 4 horns, trumpet, trombone, timpano, bass drum chime, glockenspiel, snare drum, suspended cymbal, tam-tam, triangle, vibraphone, woodblock, xylophone, and strings

Estimated duration: 6 minutes

After the success of Rhapsody in Blue made George Gershwin a household name, the young composer set himself the daunting task of writing 24 preludes for solo piano. He began early in 1925, but quickly abandoned the project, probably for lack of time. Between January 1925 and the premiere of Gershwin’s three preludes in December 1926, the composer wrote no less than four Broadway shows, made two trips to Europe, and composed and performed his Concerto in F with the New York Philharmonic.

These three concise, highly atmospheric pieces have become favorites with both musicians and audiences since their premiere. Arrangements for small orchestra, solo instruments and piano, particularly for violin, clarinet, and other winds, have proved as popular as Gershwin’s original versions. The first prelude centers on a distinctive blue note theme set to a syncopated jazz rhythm. Gershwin described the second prelude as “a sort of blues lullaby;” its languid melody suggests both fatigue and melancholy. The third piece, which Gershwin referred to as “the Spanish prelude,” combines a striking offbeat rhythmic motif with jazz-flavored melodies.

Camille Saint-saËns

Canival of the Animals

Composer: born October 9, 1835, Paris; died December 16, 1921, Algiers

Work composed: February 1886

World premiere: March 3, 1886, in a private concert hosted by cellist Charles Lebouc in Paris.

Instrumentation: 2 solo pianos, flute (doubling piccolo), clarinet, glass harmonica (or glockenspiel), xylophone, and strings

Estimated duration: 22 minutes

Camille Saint-Saëns occupies a pivotal place in the history of French music. His numerous compositions include works in every genre, and, stylistically, his music bridges the gap between Berlioz and Debussy. (Before Saint-Saëns, 19th-century French music was virtually synonymous with opera; Berlioz’ Symphonie fantastique is a notable, but isolated, exception.)

Through his many instrumental works, Saint-Saëns expanded the boundaries of French music to include a broad array of orchestral and chamber works, thus raising the profile of French music internationally.

Saint-Saëns wanted his music to outlive him, and to be remembered as a significant composer. Ironically, he is best known today for his Carnival of the Animals, a satirical “witty fantasy burlesque,” in the words of a colleague, and one he refused to have published during his lifetime, fearing it would tarnish his reputation as a writer of “serious” music. (Interestingly, Saint-Saëns also stipulated in his will that Carnival be published after his death; Durand brought out the first edition in 1922). Originally written for two pianos and chamber ensemble, Carnival of the Animals has delighted children and adults for more than a century. Excerpts from Carnival have also entered popular culture through classic cartoons, films, and television commercials.

In 1885, Saint-Saëns embarked on an extensive concert tour of Germany, but his well-publicized negative opinions on the music of Richard Wagner enraged German audiences, and many of Saint-Saëns scheduled concerts were abruptly cancelled. In January 1886, Saint-Saëns took himself off to an out-of-the-way Austrian village to rest and recover. While there, Saint-Saëns amused himself by writing a humorous, satirical suite, each movement depicting a different animal.

Musical jokes and well-known quotations from other works appear throughout Carnival, which opens with a glittering tremolo of an Introduction that gives way to the magisterial Royal March of the Lion, music befitting the all-powerful King of the Jungle. Saint-Saëns effectively captures the hither-and-thither bustle of Hens and Roosters darting about, pecking at seeds on the ground while the clarinet squawks the rooster’s crow. Both pianists execute a headlong gallop up and down the keyboard as Wild Donkeys race past. Saint-Saëns pokes fun at the Tortoises’ sluggish pace with a slowed-down-to-a-crawl version of the famous high-stepping theme of the French Can-Can. The Elephant waltzes to a gently lumbering tune in the double basses, accompanied by delicate flourishes from the pianos. The pianos jumping chords depict Kangaroos hopping here and there, pausing now and then to look around. In The Aquarium, lissome fishes swim through sun-dappled water, while the strings’ flowing melody hints at mysterious underwater realms, accented by sharp pings of the glockenspiel and the pianos’ sinuous accompaniment.

The bray of Donkeys is featured in the brief Characters With Long Ears. Next, the pianos establish a quiet forest scene for The Cuckoo, whose characteristic call is sounded by the clarinet. Flocks of colorful tuneful birds surround us in The Aviary, as the flute’s nimble fluttering evokes their breathless flights. In the original score, Saint-Saëns tells the Pianists to “imitate the hesitant style and awkwardness of a beginner,” as they play a series of tedious scales and other practice exercises. In Fossils, the only non-living animals in the Carnival, Saint-Saëns borrows from his own Danse macabre to portray Fossils dancing to the metallic staccato sound of the xylophone. Quotes from other well-known tunes including “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” the French children’s song “Au clair de la lune,” and a quick nod to an aria from Rossini’s Barber of Seville are also featured.

The Swan is the only movement from Carnival that Saint-Saëns allowed to be published during his lifetime, in an arrangement for piano and cello. The piano’s graceful, understated arpeggios support the cello’s fluid unbroken melody as the swan glides with seeming effortlessness over the waters of a still pond.

In the joyful Finale, Saint-Saëns reprises snippets from previous movements, as the animals celebrate. True to form, the Donkeys have the last word, hee-hawing the Carnival to a close.

When Carnival was published and publicly performed after Saint-Saëns death, it was hailed by all as an unqualified delight. The newspaper Le Figaro’s review was typical: “We cannot describe the cries of admiring joy let loose by an enthusiastic public. In the immense oeuvre of Camille Saint-Saëns, The Carnival of the Animals is certainly one of his magnificent masterpieces. From the first note to the last it is an uninterrupted outpouring of a spirit of the highest and noblest comedy. In every bar, at every point, there are unexpected and irresistible finds. Themes, whimsical ideas, instrumentation compete with buffoonery, grace and science …”

Andrew Norman

Drip, Blip, Sparkle, Spin, Glint, Glide, Glow, Float, Flop, Chop, Pop, Shatter, Splash

Composer: born October 31, 1979, Grand Rapids, MI

Work composed: Commissioned by the Minnesota Orchestra for their Young People’s Concert Series in 2005.

World premiere: Bill Schrickel led the Minnesota Orchestra in the premiere on November 2, 2005, in Orchestra Hall, Minneapolis, MN.

Instrumentation: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 3 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, brake drum, crotales, ratchet, snare drum, slapstick, tambourine, tam-tam, triangle, vibraphone, woodblock, xylophone, piano and strings

Estimated duration: 4 minutes

Andrew Norman is a composer, educator, and advocate for the music of others. Praised as “the leading American composer of his generation” by the Los Angeles Times, and “one of the most gifted and respected composers of his generation” by the New York Times, Norman has established himself as a significant voice in American classical music.

Norman’s music often takes inspiration from architectural structures and visual cues. His music draws on an eclectic mix of instrumental sounds and notational practices, and it has been cited in the New York Times for its “daring juxtapositions and dazzling colors,” and in the Los Angeles Times for its “Chaplinesque” wit.

Drip, Blip, Sparkle, Spin, Glint, Glide, Glow, Float, Flop, Chop, Pop, Shatter, Splash was conceived as a “get-to-know-you” piece to introduce young listeners to the multifaceted sounds of the orchestra. “The process of writing it was a bit like making a tossed salad,” says Norman. “I chopped up sounds from the orchestra – one sound for each of the thirteen verbs in the title – and then I tossed them all together and called it a piece.”

The four-minute work whizzes by with the hyperkinetic energy of a Tom & Jerry cartoon. Each word of the title is delightfully and recognizably embodied by myriad, disparate sounds, from a battery of percussion instruments to muted brasses to bows playing col legno (on the wood) and a single woodblock ticking with anticipatory hold-your-breath excitement. Audience members should note that the verbs of the title are not necessarily depicted in order, but are encouraged to identify each one nonetheless.

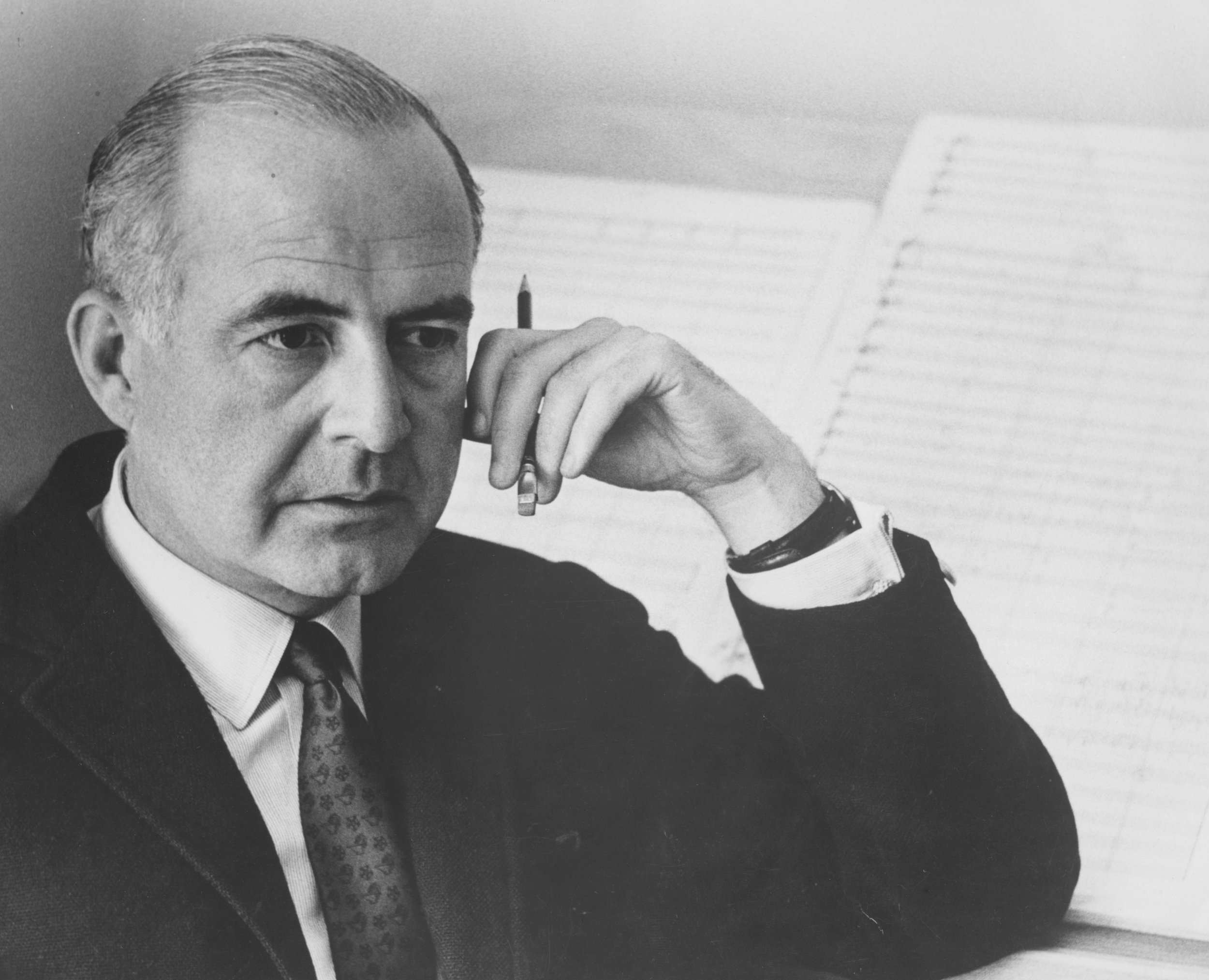

aaron copland

Four Dance Episodes from Rodeo

Composer: born November 14, 1900, Brooklyn, NY; died December 2, 1990, North Tarrytown, NY

Work composed: The ballet Rodeo, from which this suite of dances is adapted, was commissioned in 1942, by the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, with choreography by Agnes de Mille. Shortly after its premiere in October 1942, Copland arranged the Four Dance Episodes for orchestra.

World premiere: Alexander Smallens led the New York Philharmonic at the Stadium Concerts in July 1943

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (2 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, orchestra bells, slapstick, snare drum, triangle, wood block, xylophone, harp, piano, celesta, and strings.

Estimated duration: 18 minutes

When choreographer Agnes de Mille approached Aaron Copland about collaborating on a new “cowboy ballet,” Copland was less than enthusiastic. Copland’s 1938 ballet about the outlaw Billy the Kid had already given the composer the opportunity to explore Western musical themes in his work, and he saw de Mille’s project as more of the same. But de Mille, then a young and largely unknown choreographer, convinced the skeptical Copland her ballet was sufficiently different from Billy the Kid – a basic, universally appealing story set against the epic sweep of the American West – and Copland eventually agreed.

De Mille’s scenario featured a tomboyish Cowgirl from Burnt Ranch who shows up the ranch hands by out-lassoing them while roping bucking broncos. She is drawn to the Head Wrangler, who takes little notice of her, despite her obvious skills as a cowboy, until she puts on a pretty dress and makes eyes at him at the Saturday night barn dance.

As he did in Billy the Kid, Copland makes use of several authentic cowboy songs. After a high-energy brass introduction, Buckaroo Holiday features the song “If He Be a Buckaroo by His Trade,” (trombone solo approximately halfway through the movement). In the gentle Corral Nocturne, Copland quotes the song “Sis Joe” (about a train named Sis Joe heading for California’s Gold Rush country). By slowing down the song’s usual tempo, Copland creates an intimate, wistful interlude that captures the Cowgirl’s loneliness. The relaxed, low-key Saturday Night Waltz features a famous cowboy song, “I Ride An Old Paint. Hoe Down is the most recognized movement from Rodeo, thanks to its use in a popular commercial advertising American beef. In the final scene of the ballet, at a boisterous hoe-down, the cowgirl appears in a party dress, and the cowboys finally notice her. After a rhythmic introduction, “Bonaparte’s Retreat,” “McLeod’s Reel,” and other square dances fill the air with foot-stomping, thigh-slapping tunes.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

Program Notes: The Four Seasons Mixtape

Notes about:

Mendelssohn’s Overture from A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Ortiz’s La Calaca for String Orchestra

The Four Seasons Mixtape:

Vivaldi’s L’estate (Summer)

Richter’s Autumn from The Four Seasons Recomposed

Ysaÿe’s Chant d’hiver (Wintersong)

Piazzolla’s Primavera portena (Beunos Aires Spring)

Program Notes for November 1 & 2, 2024

The Four Seasons Mixtape

Felix Mendelssohn

Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Op. 21

Composer: born February 3, 1809, Hamburg; died November 4, 1847, Leipzig

Work composed: 1826

World premiere: Mendelssohn’s first version of the Overture was a two-piano arrangement for himself and his sister Fanny, which they premiered at their home in Berlin on November 19, 1826, for their piano teacher, Ignaz Moscheles. After that performance, Mendelssohn scored the work for orchestra and conducted the first performance of the orchestral version himself the following February in the city of Stettin.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, tuba, timpani, and strings.

Estimated duration: 11 minutes

In July 1826, Felix Mendelssohn began composing what would become one of his most enduring works. Immediately upon its completion, the Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream established the 17-year-old Mendelssohn as a composer of depth and astonishing maturity.

Young Felix and his family were ardent fans of Shakespeare, whose works had been translated into German in 1790. Mendelssohn’s grandfather Moses had read the plays in English and had attempted some translations of his own, including bits from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Felix and his older sister, the equally talented Fanny, immediately took to the fanciful play and staged a series of at-home performances, each child playing multiple roles. In a letter to their sister Rebecka some years after the Overture was composed, Fanny wrote, “Yesterday we were thinking about how the Midsummer Night’s Dream has always been such an inseparable part of our household, how we read all the different roles at various ages, from Peaseblossom to Hermia and Helena … We have really grown up together with the Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Felix, in particular, has made it his own.”

Much more than a simple introduction, Mendelssohn’s Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream serves as the perfect musical description of Shakespeare’s play, which was Mendelssohn’s intention. He thought of the work as a kind of mini-tone poem, rather than a musical prologue to the play itself. In just twelve minutes, Mendelssohn captures the airy magic that imbues the story: the opening chords representing the enchanted forest; the lissome, iridescent violin passages evoking fairies fluttering here and there; the alternately affectionate and turbulent encounters among the four lovers; the dismaying bray of Bottom after he is transformed into a donkey. It is a stunning achievement for a composer of any age.

While he was at work on the Overture, Mendelssohn played violin in an orchestra that performed the overture to Carl Maria von Weber’s opera Oberon. In a letter to his father and sister, Mendelssohn sketched out several of its themes, all musical representations of ideas from the opera’s libretto. This experience suggested to Mendelssohn that he intertwine recurring motifs into his own Overture that would, in his words, “weave like delicate threads throughout the whole.”

Gabriela Ortiz

La Calaca for String Orchestra (The Skull)

Composer: born December 20, 1964, Mexico City

Work composed: originally the final movement of Altar de Muertos, a string quartet written for and commissioned by the Kronos Quartet in 1996-97. Arranged for string orchestra in 2021

World premiere: John Adams led the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra at Libbey Bowl in Ojai, CA, on September 19, 2021.

Instrumentation: string orchestra

Estimated duration: 10 minutes

Born into a musical family, Gabriela Ortiz has always felt she didn’t choose music – music chose her. Her parents were founding members of the group Los Folkloristas, a renowned music ensemble dedicated to performing Latin American folk music. Growing up in cosmopolitan Mexico City, Ortiz’s music education was multifaceted; she played charango and guitar with Los Folkloristas while also studying classical piano. Later, Ortiz was mentored in composition by renowned Mexican composers Mario Lavista, Julio Estrada, Federico Ibarra, and Daniel Catán. Ortiz continued her studies in Europe, earning a doctorate in composition and electronic music from London’s City University under the guidance of Simon Emmerson.

Ortiz’s music incorporates seemingly disparate musical worlds, from traditional and popular idioms to avant-garde techniques and multimedia works. This is, perhaps, the most salient characteristic of her oeuvre: an ingenious merging of distinct sonic worlds. While Ortiz continues to draw inspiration from Mexican subjects, she is interested in composing music that speaks to international audiences.

Conductor Gustavo Dudamel, a longtime champion of Ortiz’s music, stated: “Gabriela is one of the most talented composers in the world – not only in Mexico, not only in our continent – in the world. Her ability to bring colors, to bring rhythm and harmonies that connect with you is something beautiful, something unique.” Under Dudamel’s direction, the Los Angeles Philharmonic has commissioned and premiered seven works by Ortiz in recent years, including her ballet Revolución diamantina (2023), her violin concerto Altar de Cuerda (2021), and Kauyumari (2021) for orchestra. These three works are featured on the album Revolución diamantina, which was released in June 2024.

La Calaca began as the final movement of Altar de Muertos (Altar of the Dead), a string quartet commissioned by the Kronos Quartet. Altar de Muertos reflects the traditions and festivities of the Day of the Dead. Ortiz writes, “The tradition of the Day of the Dead festivities in Mexico is the source of inspiration for the creation of a work for string quartet whose ideas could reflect the internal search between the real and the magic, a duality always present in Mexican culture, from the past to this present.”

Each movement of Altar embodies the “diverse moods, traditions and the spiritual worlds which shape the global concept of death in Mexico, plus my own personal concept of death,” Ortiz explains. In La Calaca, the music expresses “Syncretism [in religion, the practice of merging beliefs and rituals from disparate traditions] and the concept of death in modern Mexico, chaos and the richness of multiple symbols, where the duality of life is always present: sacred and profane; good and evil; night and day; joy and sorrow. This movement reflects a musical world full of joy, vitality, and a great expressive force. At the end of La Calaca I decided to quote a melody of Huichol origin, which attracted me when I first heard it. That melody was sung by Familia de la Cruz. The Huichol culture lives in the State of Nayarit, Mexico. Their musical art is always found in ceremonial and ritual life.”

The Four Seasons Mixtape

“A mixtape, harkening back to the days of holding a cassette recorder up to the radio, has come into the modern lexicon as a compilation of different musical selections, often from different artists or composers, and usually evoking some similar mood or subject matter,” writes Modesto Symphony Orchestra’s Music Director Nicholas Hersh. “In fact, Vivaldi’s Four Seasons is perhaps an early representation of this concept: a set of four violin concerti, each of which can be performed separately, but when taken together they form a greater narrative. Our MSO ‘Four Seasons Mixtape’ takes this a step further by assigning each season to a different composer. Vivaldi’s original Summer sets the tone, and Max Richter’s Autumn [Recomposed] follows it up with a ‘remix’ of the Baroque sound with modern harmony and syncopation. Belgian violin virtuoso Eugene Ysaÿe’s Wintersong imparts a Romantic sumptuousness to an otherwise bleak season, and finally Astor Piazzolla takes us home with his uproarious Buenos Aires Spring, infused with the rhythms of the Tango.

“It is no easy feat to perform such wildly different musical styles as part of the same whole, and I am so grateful to Audrey Wright for realizing this Mixtape with us!”

Antonio Vivaldi

“L’estate” (Summer) from The Four Seasons for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 8 No 2

Composer: born March 4, 1678, Venice; died July 27/28, 1741, Vienna

Work composed: published 1725. Dedicated to Count Wenceslas Morzin.

World premiere: undocumented

Instrumentation: solo violin, continuo, and strings

Estimated duration: 11.5 minutes

Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons are some of the most recognizable and most performed Baroque works ever written. They have also been used by numerous companies to sell products, from diamonds to high-end cars to computers. With that level of exposure, it is easy to assume we “know” The Four Seasons, but there is more to these concertos than meets the eye, or the ear.

The Four Seasons are part of a larger collection of concertos Vivaldi titled Il cimento dell’armonia e dell’inventione (The contest between harmony and invention). Each concerto is accompanied by a sonnet, possibly written by Vivaldi himself, which gives specific descriptions of the music as it unfolds.

Summer’s slow introduction evokes a hot, humid summer day: “Under the merciless summer sun languishes man and flock; the pine tree burns … ” Lethargic birdcalls are abruptly interrupted by violent thunderstorms. In the slow movement, the soloist (shepherd) cries out in fear for his flock in the blistering heat. While he laments, the ensemble becomes buzzing flies. The final movement morphs into a tremendous hailstorm that destroys the crops.

Max Richter

“Autumn” from The Four Seasons Recomposed

Composer: born March 22, 1966, Hamelin, Lower Saxony, West Germany

Work composed: 2011-12

World premiere: André de Ridder led the Britten Sinfonietta with violinist Daniel Hope at the Barbican Centre on October 31, 2012, in London.

Instrumentation: solo violin and strings

Estimated duration: 8 minutes

Max Richter’s fusion of classical music and electronic technology, as heard in his genre-defining solo albums and numerous scores for film, TV, dance, art, and fashion, has blazed a trail for a generation of musicians.

In 2011, the recording label Deutsche Grammophon invited Richter to join its acclaimed Recomposed series, in which contemporary artists are invited to re-work a traditional piece of music. Richter chose Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons. In a 2014 interview with the website Classic FM, Richter explained, “When I was a young child I fell in love with Vivaldi’s original, but over the years, hearing it principally in shopping centres, advertising jingles, on telephone hold systems and similar places, I stopped being able to hear it as music; it had become an irritant – much to my dismay! So I set out to try to find a new way to engage with this wonderful material, by writing through it anew – similarly to how scribes once illuminated manuscripts – and thus rediscovering it for myself. I deliberately didn’t want to give it a modernist imprint but to remain in sympathy and in keeping with Vivaldi’s own musical language.”

“ … The key thing for me to figure out when navigating through this material was just how much Vivaldi and how much me was happening at any point,” Richter continued. “Three quarters of the notes in the new score are mine, but that is not the whole story. Vivaldi’s DNA is omnipresent in the work, and trying to take that into account at all times was the key challenge for me.”

Richter’s version of “Autumn” inserts syncopations (rhythmic off-beats) and subtle electronics into Vivaldi’s original music; the overall effect blurs the boundaries between which phrases are Vivaldi’s and which are Richter’s to a remarkable degree. “I’ve used electronics in several movements, subtle, almost inaudible things to do with the bass,” says Richter, “but I wanted certain moments to connect to the whole electronic universe that is so much part of our musical language today.”

During the recording sessions for Richter’s Recomposed Four Seasons, the composer adds, “In the second movement of ‘Autumn,’ I asked the harpsichordist Raphael Alpermann to play in what is a rather old-fashioned way, very regularly, rather like a ticking clock. That was partly because I didn’t want the harpsichord part to be attention-seeking, but also because that style connects to various pop records from the 1970s where the harpsichord or Clavinet was featured, including various Beach Boys albums and the Beatles’ Abbey Road.”

Eugène Ysaÿe

Chant d’hiver (Winter Song)

Composer: born July 16, 1858, Liège, Belgium; died May 12, 1931, Liège

Work composed: 1902

World premiere: undocumented

Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 12.5 minutes

Known during his lifetime as “The King of the Violin,” Eugène Ysaÿe was also a noted composer and conductor. Born 18 years after the death of the legendary Italian violinist Niccolò Paganini, the Belgian virtuoso was – and is – widely considered the greatest violinist of his time. This opinion was shared by the foremost composers of the latter 19th – and early 20th-century, including Claude Debussy, Ernest Chausson, Gabriel Faurè, and fellow Belgian César Franck, all of whom dedicated works to Ysaÿe.

Ysaÿe’s Chant d’hiver was inspired by a famous poem from medieval French poet François Villon (c.1431-after 1463). The poem, known in English as “Ballad of the Ladies of Bygone Times,” features a wistful refrain, “But where are the snows of yesteryear?” The exquisite melancholy of the soloist’s long phrases and the orchestra’s deft accompaniment evoke an air of longing – and also captures the quintessentially Romantic situation in which one is sad while simultaneously finding an odd pleasure in it.

Astor Piazzolla

“Primavera porteña” from Cuatro estaciones porteñas de Buenos Aires (“Spring” from The Four Seasons of Buenos Aires)

Composer: born March 11, 1921, Mar del Plata, Argentina; died July 5, 1992, Buenos Aires

Work composed: Piazzolla originally composed the Cuatro estaciones porteñas de Buenos Aires for Melenita de oro, a play by his countryman, Alberto Rodríguez Muñoz. The movements were written individually, between the years 1965 -1970, and Piazzolla did not originally intend them to be performed as a single work. The original version of Cuatro estaciones is scored for Piazzolla’s quintet, which consisted of violin, electric guitar, piano, bass, and bandóneon (a large button accordion). Tonight’s arrangement, for solo violin and string orchestra, was created in 1999 by Leonid Desyatnikov for violinist Gidon Kremer.

World premiere: Piazzolla and his quintet played the Cuatro estaciones for the first time at the Teatro Regina in Buenos Aires, on May 19, 1970.

Instrumentation: solo violin and strings

Estimated duration: 5 minutes

“For me, tango was always for the ear rather than the feet.” – Astor Piazzolla

Astor Piazzolla and tango are inseparably linked. He took a dance from the back rooms of Argentinean brothels and blurred the lines between popular and “art” music to such an extent that such categories no longer apply.

In the mid-1950s, Piazzolla went to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger, one of the 20th century’s most renowned composition teachers. She was unimpressed with the scores he showed her but, after insisting he play her some of his own tangos, she declared, “Astor, this is beautiful. I like it a lot. Here is the true Piazzolla – do not ever leave him.” Piazzolla later called this “the great revelation of my musical life,” and followed Boulanger’s advice. He took tango’s raw passion and fire, with its powerful rhythms and edgy melodies, and made it an essential part of classical repertoire.

The version of the Cuatro estaciones porteñas de Buenos Aires heard on tonight’s program was created in 1999 by Russian composer/arranger Leonid Desyatnikov, at the request of violinist Gidon Kremer. Desyatnikov not only arranged Cuatro estaciones, but also inserted quotes from Antonio Vivaldi’s Four Seasons into Piazzolla’s music.

Tango’s musical style requires several string techniques not often heard in classical music: wailing glissandos, sharp pizzicatos that threaten to break strings, bouncing harmonics and, in particular, a harsh, scratchy, distinctly “un-pretty” manner of bowing, sometimes using the wood, rather than the hair, of the bow.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

Program Notes: Branford Marsalis with the Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Notes about:

Borodin's “Polovtsian Dances” from Prince Igor

Milhaud’s Scaramouche, Op. 165

Williams' “Escapades” from Catch Me If You Can

Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances for Large Orchestra, Op. 45

Program Notes for october 5th, 2024

Branford Marsalis with the

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Alexander Borodin

“Polovtsian Dances” from Prince Igor

Composer: born November 12, 1833, St. Petersburg; died February 27, 1887, St. Petersburg

Work composed: Borodin worked on Prince Igor from 1869-1874 and intermittently thereafter, but it remained uncompleted at the time of his death. Borodin’s friend and colleague, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, orchestrated the Polovtsian Dances.

World premiere: Eduard Nápravnik led the first performance of Prince Igor on November 16, 1890, at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg

Instrumentation: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes (1 doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, glockenspiel, snare drum, suspended cymbal, tambourine, triangle, harp, and strings

Estimated duration: 14 minutes

Alexander Borodin, like the other members of the Kucha, or Mighty Five, wrote music in his spare time. (A music critic coined the nickname “The Kucha” in reference to a group of influential 19th century Russian composers based in St. Petersburg. In addition to Borodin, the group included Mily Balakirev, César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov). A chemist by profession, Borodin made significant contributions to both his profession and his avocation.

The Kucha aspired to create authentically Russian music, free from the domination of German aesthetics. To this end, the Kucha featured indigenous folk songs and dances from different regions of the Russian empire.