Digital Program: Scheherazade & Márquez’s Fandango

February 13 & 14, 2026 at 7:30 pm

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Scheherazade & Márquez’s Fandango

Friday, November 14, 2025; 7:30 pm

Saturday, November 15, 2025; 7:30 pm

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PROGRAM” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Program Notes: Scheherazade & Márquez’s Fandango

Notes about:

Margaret Bonds: Selections from The Montgomery Variations

Arturo Márquez: Fandango

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: Scheherazade

Program Notes for February 13 & 14, 2026

Margaret Bonds

The Montgomery Variations

Composer: Born March 3, 1913, Chicago, Illinois; died April 26, 1972, Los Angeles, California.

Composed: 1963-1964.

Premiere: Though there are some indications that it may have boon performed in 1967, the definitive world premiere was on December 6, 2018, by the University of Connecticut Symphony Orchestra. The Montgomery Variations was finally published in 2020.

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (1 doubling piccolo and alto flute), 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, triangle, cymbals, wood block, tambourine, large drum, harp, and strings

Duration: 15:00.

Background

Composer and pianist Margaret Bonds was born in Chicago, into a family prominent in the African American community. After her father, a well-respected physician, and mother divorced, she grew up in her mother’s house, surrounded by music...and by many of the leading Black intellectual figures and musicians of the day. In the 1920s and 1930s, there was a Chicago Renaissance in parallel to the well-known Harlem Renaissance, and the home of Margaret’s mother, Estelle Bonds, became a gathering-spot for prominent writers, artists, and musicians. Among the longterm houseguests was composer Florence Price, with whom Bonds later studied composition. She entered Northwestern University at age 16, and though she earned Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees there, she found the environment to be racist and hostile. According to Bonds, what saved her was encountering the poem The Negro Speaks of Rivers by Langston Hughes (1902-1967):

Because in that poem he tells how great the black man is. And if I had any misgivings, which I would have to have—here you are in a setup where the restaurants won’t serve you and you’re going to college, you’re sacrificing, trying to get through school—and I know that poem helped save me.

Bonds later struck up a close friendship with Hughes, and set several of his works to music, including a Christmas cantata, The Ballad of the Brown King (1960). While still at Northwestern, Bonds’s composition Sea Ghost won a national prize, and in 1933, she performed as a piano soloist with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (the first Black soloist in the orchestra’s history). In 1939, she moved to New York City, where she would spend most of her career. Bonds studied piano and composition at the Julliard School, but was also obliged to earn a living, later recalling: “no job was too lousy; I played all sorts of gigs, wrote ensembles, played rehearsal music, and did any chief cook and bottle washer job just so I could be honest and do what I wanted.” What she wanted to do, clearly, was to make music, and over the next three decades she was successful as a composer, but also as a performer, promoter, educator, community leader, and advocate for Black music. The death of Langston Hughes in 1967 seems to have been an emotional turning-point for Bonds, and she moved to Los Angeles in 1968 to work as an educator. She died there in 1972, just a few weeks after the successful premiere of her Credo by the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Montgomery, Alabama was one of the epicenters of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. One of the defining events was the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955-56, sparked by activist Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat to a white rider on a segregated Montgomery bus. This marked one of the first great victories of the movement, ending in the official desegregation of Montgomery’s buses. One of the leaders of the boycott was the pastor of Montgomery’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Martin Luther King Jr. In 1957, King (to whom Bonds would later dedicate The Montgomery Variations) and other church leaders created the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which would become a major force in the nonviolent civil rights struggle.

In 1963, Bonds was on a concert tour to Montgomery and the surrounding area and was deeply inspired by King and the movement. She began work on The Montgomery Variations, one of her very few purely orchestral pieces almost immediately finishing after the dark day of September 15. She completed the orchestration in 1964. A noted scholar of African-American music, Tammy Kernodle, describes The Montgomery Variations as follows:

The thematic narrative of the work follows the chronology of 1955 to 1963, which correlates with the initiation of the Montgomery bus boycott, the rise of Dr. King, and the initiation of nonviolent direct-action campaigns throughout the South. Bonds ends the narrative framework with one of the seminal events of the Movement—the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, on September 15, 1963, which killed four little girls, and its aftermath of grief. Coming only two weeks following Dr. King’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the bombing signified the start of a period of overt violence that pervaded the movement during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

What You’ll Hear

The Montgomery Variations is in seven movements, four of which are played here. Black spirituals have been a touchstone for many African-American composers throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, and the primary musical theme, heard throughout, is the spiritual, I Want Jesus To Walk With Me.

Bonds describes the action in the opening movement, I. The Decision: “Under the leadership of Martin Luther King, Jr., and SCLC, Negroes in Montgomery decided to boycott the bus company and to fight for their rights as citizens.” After a dramatic pair of drum rolls, the spiritual theme is laid out by the brasses. The music of this brief introduction conveys a clear sense of resolve throughout. II. Prayer Meeting is much more hushed and fervent, throughout, climaxing in a subdued brass passage and a bluesy trombone solo. Describing III: March, Bonds wrote: “The Spirit of the Nazarene marching with them, the Negroes of Montgomery walked to their work rather than be segregated on the buses. The entire world, symbolically with them, marches.” This is quietly defiant music beginning with a solo bassoon above an insistent string rhythm, that swells inexorably at the end as ever more marchers join in. About the final movement, VII. Benediction, Bonds wrote: “A benign God, Father and Mother to all people, pours forth Love to His children—the good and the bad alike.” This final section starts quietly, almost wistfully, with a series of woodwind solos, eventually growing to a grand transformation of the spiritual theme, and a quiet prayerful ending.

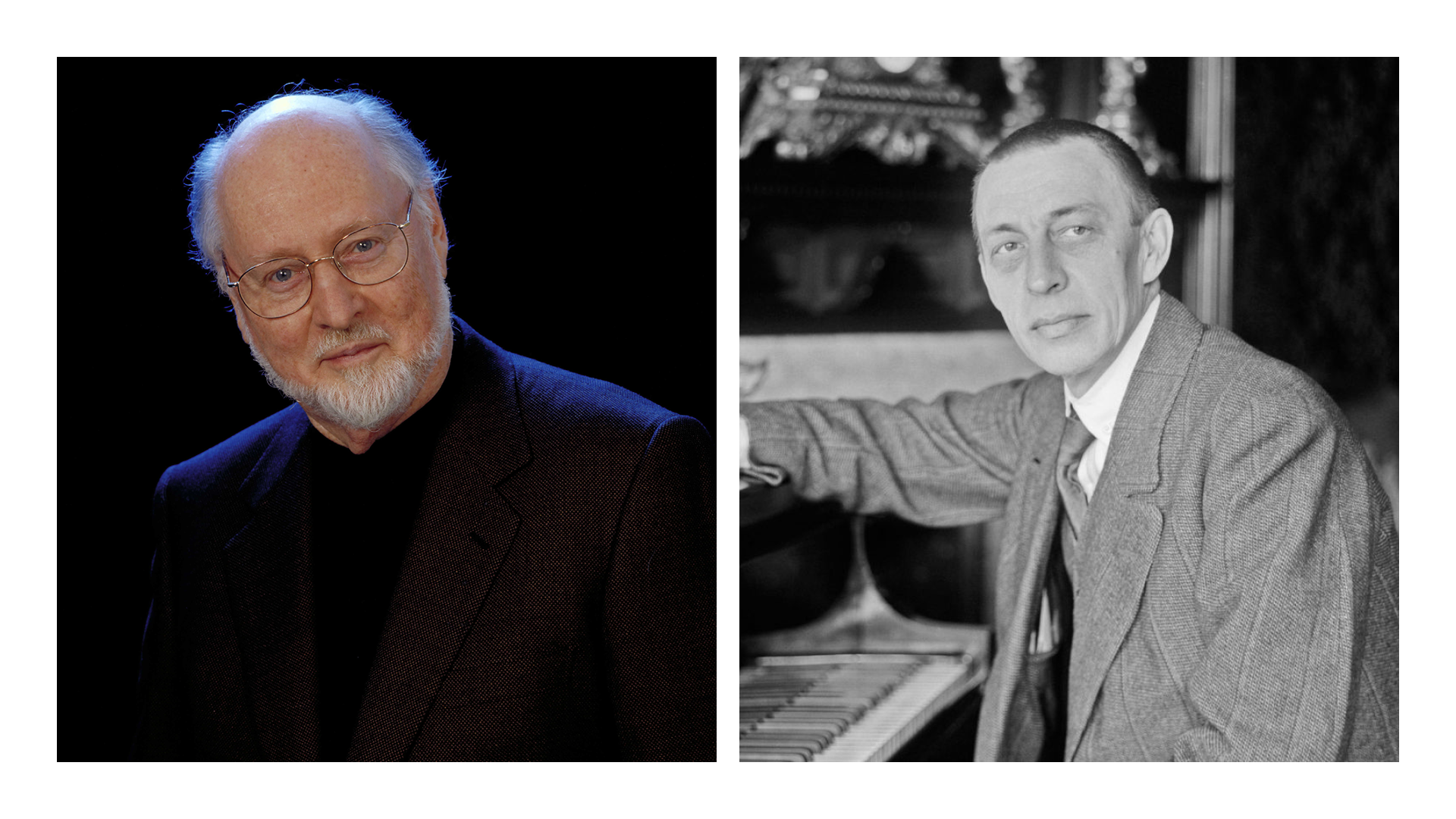

Arturo Márquez

Fandango

Composer: Born December 20, 1950, Álamos, Mexico.

Work composed: 2020. Commissioned for Anne Akiko Myers.

World premiere: In Los Angeles, on August 24, 2021, by violinist Anne Akiko Myers, with the Los Angeles, Philharmonic, led by Gustavo Dudamel.

Instrumentation: solo violin, piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, bass, trombone, tuba, timpani, snare drum, cymbals, bass drum, claves, cajon, güiro, harp, and strings.

Estimated duration: 30:00.

Background

Arturo Márquez, one of Mexico’s most successful contemporary composers, was born in the state of Sonora. When he was 12 years old, his family moved to a suburb of Los Angeles, where he studied piano, violin, and trombone. Márquez later recalled that “My adolescence was spent listening to Javier Solis [the famous Mexican singer/actor], sounds of mariachi, the Beatles, Doors, Carlos Santana and Chopin.” He later studied at the Conservatory of Music of Mexico, with the great French composer Jacques Castérède in Paris, and at the California Institute of the Arts. He is on the faculty of the National Autonomous University in Mexico City. Márquez frequently uses Mexican and other Latin folk influences in his works, and his best-known series of works are the Danzónes he began composing in the 1990s for orchestra and other ensembles.

Márquez notes regarding the Fandango that:

The Fandango is known worldwide as a popular Spanish dance and specifically, as one of the fundamental parts (Palos) of Flamenco. Since its appearance in the 18th century, various composers such as S. de Murcia, D. Scarlatti, L. Bocherini, Padre Soler, and W. A. Mozart, among others, have included the Fandango in concert music. What is little known in the world is that immediately upon its appearance in Spain, the Fandango moved to the Americas where it acquired personalities according to the land that adopted and cultivated it. Today, we can still find it in countries such as Ecuador, Colombia and Mexico—in the latter specifically in the state of Veracruz and in the Huasteca area, part of seven states in eastern Mexico. Here the Fandango acquires a tinge different from the Spanish genre; for centuries, it has been part of a special festival for musicians, singers, poets and dancers. Everyone gathers around a wooden platform to stamp their feet, sing and improvise ten-line stanzas bout the occasion.

In 2018 I received an email from violinist Anne Akiko Meyers, a wonderful musician, where she proposed to me the possibility of writing a work for violin and orchestra that had to do with Mexican music. The proposal interested and fascinated me from that very moment, not only because of Maestra Meyers’s emotional aesthetic proposal but also because of my admiration for her musicality, virtuosity and, above all, for her courage in proposing a concerto so out of the ordinary. I had already tried, unsuccessfully, to compose a violin concerto some 20 years earlier with ideas that were based on the Mexican Fandango. I had known this music since I was a child, listening to it in the cinema, on the radio and hearing to my father (Arturo Márquez Sr.), a mariachi violinist, play Huastecos and mariachi music. Also, since the 1990s I have been admiring the Fandango in various parts of Mexico. I would like to mention that the violin was my first instrument when I was 14 years old (1965). Remarkably, I studied it in La Puente, California in Los Angeles County where this work will be premiered with the wonderful Los Angeles Philharmonic under the direction of Gustavo Dudamel, whom I admire very much. This is a beautiful coincidence, as I have no doubt that the Fandango was danced in California in the 18th and 19th centuries.

What You’ll Hear

Márquez provides the following description of the work itself:

Fandango for violin and orchestra is formally a concerto in three movements:

Folia Tropical

Plegaria (Prayer) (Chaconne)

Fandanguito

The first movement, Folia Tropical, is in the sonata form of a traditional classical concerto: introduction, exposition with its two themes, bridge, development and recapitulation. The introduction and the two themes share the same motif in a totally different way. Emotionally, the introduction is a call to the remote history of the Fandango; the first theme and the bridge, this one totally rhythmic, are based on the Caribbean “Clave” rhythm, and the second is eminently expressive, almost like a romantic Bolero. Folias are ancient dances that come from Portugal and Spain. However, also the root and meaning of this word also takes us to the French word “folie”—madness.

The second movement Plegaria pays tribute to the Huapango mariachi together with the Spanish Fandango, both in its rhythmic and emotional parts. It should be noted that one of the Palos del Flamenco Andaluz is known as the Malagueña and Mexico also has a Huapango honoring the Andalusian city of Malaga. I do not use traditional themes but there is a healthy attempt to unite both worlds; that is why this movement is the fruit of an imaginary marriage between the Huapango mariachi and Pablo Sarasate, Manuel de Falla and Issac Albeniz, three of the Spanish composers whom I most love and admire. It is also a freely treated Chaconne. Perhaps a few people know that the Chaconne as well as the Zarabanda were two dances forbidden by the Spanish Inquisition in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, long before they became part of European Baroque music. Moreover, the first written descriptions of these dances place them in colonial Mexico of these centuries.

The third movement, Fandanguito, is a tribute to the famous Malaga huasteco. The music of this region is played by violin, jarana huasteca (small rhythm guitar) and huapanguera (low guitar with 5 courses of strings). This ensemble accompanies the songs and recited or sung improvisation. The huasteco violin is one of the instruments with the most virtuosity in all of America. Its technique has certain features similar to Baroque music but with great rhythmic vitality and a rich original variety in bow strokes. Every huasteco violinist must have a personal version of this playing technique, if he wants to have and maintain prestige. This third movement is a totally free elaboration of the Fandanguito huasteco, but it maintains many of its rhythmic characteristics. It demands great virtuosity from the soloist. It is music that I have kept in my heart for decades.

I think that for every composer it is a real challenge to compose new works from old forms, especially when this repertoire is part of the fundamental structure of classical music. On the other hand, composing in this during the 2020 pandemic was not easy due to the huge human suffering. Undoubtedly my experience with this work during this period has been intense and highly emotional but I must mention that I have preserved my seven capital principles: tonality, modality, melody, rhythm, imaginary folk tradition, harmony and orchestral color.

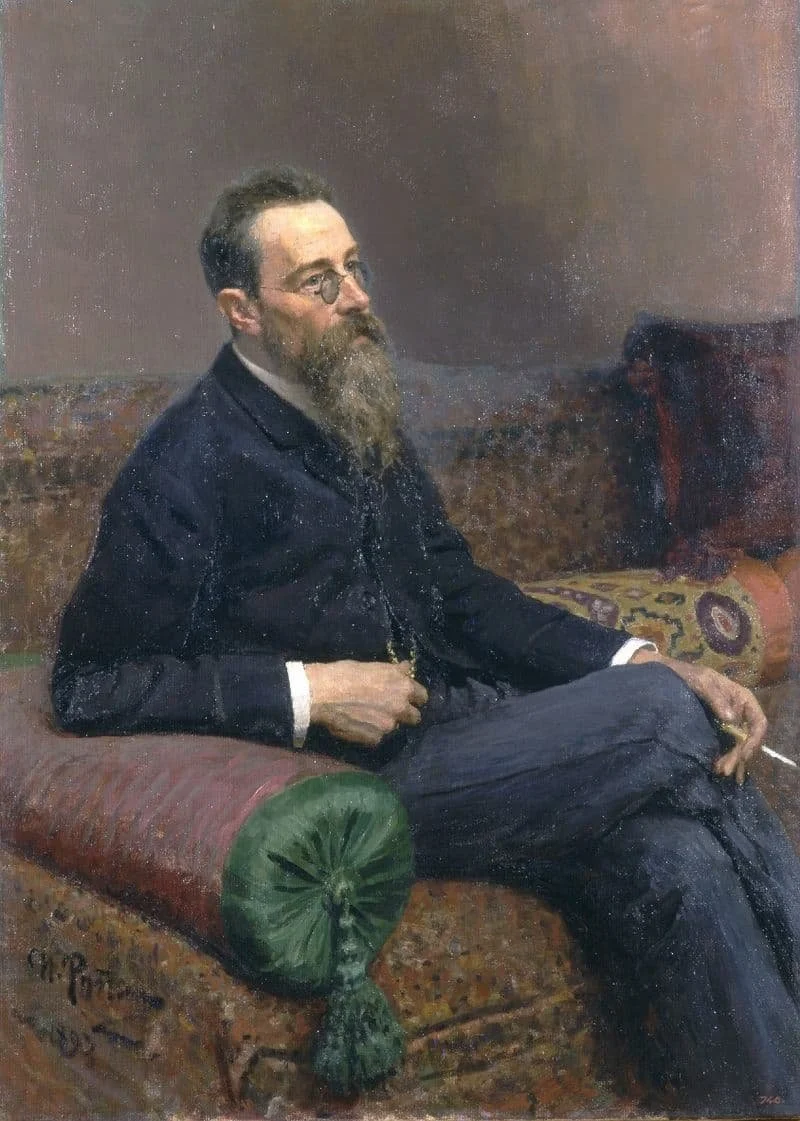

Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908)

Scheherazade: Symphonic Suite, Op. 35

Composer: Born March 18, 1844, in Tivkin, Russia; died June 21, 1908, in Liubensk, Russia.

Work composed: Rimsky-Korsakov completed Scheherazade in 1888, during his summer break from his duties at the St. Petersburg Conservatory.

World premiere: The composer conducted its premiere in St. Petersburg, on November 9, 1888.

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (2 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, cymbals, suspended cymbal, snare drum, triangle, tambourine, tamtam, harp, and strings.

Approximate duration: 40:00.

Background

The Thousand and One Nights is a collection of Arabic and Egyptian stories dating from as early as the 10th century. The framing story is that the Sultan Shahryar, convinced of the infidelity of all women, puts a series of wives to death until the Princess Scheherazade distracts him by telling him one fantastic tale after another, one each night for 1001 nights. He eventually lays aside his murderous plan. There are many versions of The Thousand and One Nights, but most of the stories, including the voyages of Sinbad and the story of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, were collected together by the 15th century. Some, including, the story of Aladdin, were added even later. 19th-century readers were fascinated by exotic settings and fairy-tales and the “Arabian Nights” fills this bill nicely—stories of love, humor, bravery, and magic. To be sure, most European, American, and Russian readers knew the collection only through carefully-edited translations that avoided the more sexually explicit bits, and accentuated the fairy-tale aspects. (An exception was the unexpurgated English translation published by Francis Burton in 1885—a highly controversial book in its time.) The tales served as the basis for innumerable works of art, literature, dance and music. The most powerful musical treatment is certainly Rimsky-Korsakov’s symphonic suite Scheherazade, which was composed in 1888.

Rimsky-Korsakov, the great Russian nationalist and leading teacher at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, first conceived of a work on stories from The Thousand and One Nights in the winter of 1887 as he was at work on his completion of Borodin’s Prince Igor. He finished Scheherazade in 1888, during his summer break from his teaching duties—at roughly the same time as he completed his equally famous Russian Easter Overture. In the earliest version, Rimsky-Korsakov gave descriptive titles to Scheherazade’s four sections: I. The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship, II. The Tale of the Kalendar Prince, III. The Young Prince and the Young Princess, and IV. Festival at Bagdad. The Sea. The Ship Goes to Pieces on a Rock Surmounted by the Bronze Statue of a Warrior. Conclusion. He was uncomfortable with a strictly programmatic interpretation, however, and before publishing the work, considered replacing the titles of the four movements with less picturesque designations: Prelude, Adagio, Ballade, and Finale. Rimsky-Korsakov did away with movement-titles altogether in the published version of the suite, but by this time the original descriptive titles were well known. He actually managed to have it both ways, however, as he later wrote in his autobiography:

In composing Scheherazade, I meant these hints to direct but slightly the hearer’s fancy on the path which my own fancy had traveled, and to leave more minute and particular conceptions as to the will and mood of each movement. All that I desired was that, if the listener liked my piece as symphonic music, he should carry away the impression that it is beyond doubt an oriental narrative of some varied fairy-tale wonders, and not merely four pieces played one after the other, and composed on the basis of themes common to all of the four movements. Why then, if this is the case, does my suite bear the specific title of Scheherazade? Because this name and the title The Arabian Nights connote in everybody’s mind the East and fairy-tale marvels—besides, certain details of the musical exposition hint at the fact that all of these are various tales of some one person (which happens to be Scheherazade) entertaining therewith her stern husband.

What You’ll Hear

Rimsky-Korsakov was an acknowledged master of scoring music for orchestra (his Principles of Orchestration is still one of the standard works on the subject)—for him, “orchestration is part of the very soul of the work.” Scheherazade may well be his masterwork in this regard—are few other works that make such effective use of orchestral color. The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship begins with a pair of themes that recur in all four movements, an angry theme from the trombones (the voice of the Sultan?) and a seductive violin solo, which despite all of Rimsky-Korsakov’s circumlocutions, must represent Princess Scheherazade herself. The body of the movement is distinctly aquatic, with a broad 6/4 theme that suggests the rolling of the waves.

There are several princes in the collection who disguise themselves as kalendars—roving holy men. After the violin announces a new story, Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Tale of the Kalendar Prince begins with a series of quiet, oriental-sounding woodwind solos, expanding into a dance for the full string section. A bold pronouncement from the solo trombone suddenly changes the mood, and the movement ends in what sounds like an extended battle scene, alternating Scheherazade’s theme with more warlike music. The next movement is a gentle contrast: The Young Prince and the Young Princess is a nostalgic interlude, with a rich dance melody (derived from Scheherazade’s theme) above a shimmering background, and a hint of oriental percussion. Scheherazade herself appears briefly, before the movement ends with a lush coda.

The finale begins with boisterous and sometimes frantic festival music that alternates with Scheherazade’s sinuous theme. The broad Sinbad music of the first movement returns in the trombones, but now the woodwinds provide the howling of hurricane winds, until a moment of crashing disaster. The movement ends with a quiet epilogue for solo violin, as Scheherazade concludes the tale.

Program notes ©2026 J. Michael Allsen